D.1Alluring Tangents¶

This Appendix contains tangential information that may be of interest to students, but too far removed from the main thread of material to warrant placement within chapters. Many of these items were prompted by student feedback on the first draft of the textbook, wanting to know more about some tantalizing piece mentioned in the text. Pick and choose according to your interests.

(sec:appDtangents:universeedge)

D.2Edge of the Universe¶

Sec. 4.1 (p. 54) built a step-wise scale out to the edge of the visible universe, which a margin note clarifies as the visible horizon of our universe. This fascinating and deep concept deserves elaboration.

Two foundations of experimental physics and cosmology are that the speed of light is finite, and the universe began in a Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago. Ample evidence supports of both claims. It should be noted that these notions were not at all accepted by scientists until the preponderance of evidence left little choice but to adopt them as how the world really appears to work.

The finite speed of light means that looking into the distance amounts to looking back in time. Here, Imperial units have a brief moment of glory, in that every foot of distance (0.3 m) is one nanosecond of time. We see the moon as it was 1.25 seconds “in the past,” the sun as it was 500 seconds (8.3 minutes) ago, and the nearest star 4.2 years back. The “nearby” Andromeda Galaxy is 2.5 million years in the past, and as we peer farther into the universe we look ever farther back in time. Indeed, at great distances we see infant galaxies in the process of forming as gravitational vacuum cleaners collecting materials from the diffuse gas that came before.

So what happens when we look 13.8 billion years into the past, when the Big Bang is alleged to have happened? Shouldn’t we see the explosion? And shouldn’t it—perhaps confusingly—be visible in all directions?

The answer is a resounding, though qualified, YES. Yes, we see evidence of the Big Bang in all directions, as a glow that appears in the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum. The Cosmic Microwave Background, or CMB, as it is called, represents the glowing plasma when the universe was just 380,000 years old and about 1,100 times smaller than it is today. We cannot see earlier than this because the hot ionized plasma

that existed before this time is opaque1 to light travel. The universe only became “clear” after this time, when the plasma cooled into neutral (mostly) hydrogen atoms. So we can see almost back to the Big Bang, at least 99.997% of the way before the scene becomes opaque.So that’s the limit to our vision, based on the idea that light has not had time to travel farther since the universe began. This is what we mean by the edge of the visible universe.

But is it a real edge? All indications are that it is certainly not. When we look 13.8 billion light years away, we just see this glowing plasma (the CMB). But in the intervening years, galaxies and stars and planets have formed in that region of space, and would appear “normal,” or mature today. So imagine a being on such a planet looking at us today, 13.8 billion light years distant. But they see us 13.8 billion years ago, when our neighborhood was still a glowing plasma well before the formation of galaxies, stars, and planets.

Let’s say the distant being is directly behind you and you are both looking off in the same direction—the alien essentially looking over your shoulder as you look directly opposite the direction to the alien. You (or the primordial gas that will someday become you) are at the limit of their vision, and they can’t see anything beyond you. You sit at their edge. But to you it’s no edge. You have no trouble seeing more “normal” universe stretching another 13.8 billion light years beyond what our distant friend can see. It’s only a perceived edge, based on the limit of light travel time.

A nice way to think of it is familiar scenes of limited vision, like in a fog or in the ocean, or even on the curved surface of Earth. All cases have a horizon: a limit to the distance visible. Yet moving to the edge of vision reveals a whole new region that was before invisible. Keep going and your starting region will no longer be visible, or within your horizon. But it has not ceased to exist.

Similarly, the universe would seem to be much larger than our visible horizon. Measurements of the “flatness” of the geometry of space suggest a universe that is at least 100 times larger than our horizon, and may in fact be unfathomably larger. We may never know for sure, as limits to light travel seal us off from direct observation of most of the universe.

D.3Cosmic Energy Conservation¶

Sec. 5.2 (p. 69) discussed the foundational principle of the conservation of energy, claiming that the principle is never violated except on cosmic scales. Besides elaborating on that point, this section follows the story of energy across vast spans of time as our sun forms and ultimately delivers energy to propel a car. We also clarify what it means for energy to be “lost” to heat.

1: . . . much as the sun, another plasma is opaque: we only see light from its outer surface

D.3.1Cosmological Exception¶

Emmy Noether was a leading mathematician in the early twentieth century who also dabbled in physics. In a very profound insight, she recognized a deep connection between symmetries in nature and conservation laws. A symmetry, in this context, is a property that looks the same from multiple vantage points. For instance, a sphere is symmetric in that it looks the same from any angle. A cylinder or vase also has symmetry about one axis, but more limited than the sphere.

The symmetries Noether considered are more subtle symmetries in time, space, and direction.

Definition D.2.1 Symmetry in time means that physics behaves the same at all times: that the laws and constants are the same, and an experiment cannot be devised that would be able to determine absolute time.

Symmetry in space means that the laws of physics are the same no matter where one goes: fundamental experiments will not differ as a function of location.

Symmetry in direction is closely related to the previous one. It says that the universe (physical law) is the same in every direction.

The insight is that these symmetries imply conservation laws. Time symmetry dictates conservation of energy. Space symmetry leads to conservation of momentum. Directional symmetry results in conservation of angular momentum.

Great. As far as we know, the latter two are satisfied by our universe. To the best of our observational capabilities, the universe appears to be homogeneous (the same everywhere) and isotropic (the same in all directions). Yes, it’s clumpy with galaxies, but by “same,” we mean that physics appears to act the same way. Therefore, substantial observational evidence supports our adopting conservation of momentum and conservation of angular momentum as a fact of our reality.

But time symmetry is a problem, because the universe does not appear to be the same for all time. It appears to have emerged from a Big Bang (see Section D.1), and was therefore much different in the past than it is now, and continues to change/evolve. An experiment to measure the effective temperature of the Cosmic Microwave Background is enough to establish one’s place on the timeline of the cosmic unfolding.

As a consequence, conservation of energy is not strictly enforced over cosmological timescales. When a photon travels across the universe, it “redshifts,” as if its wavelength were being stretched along with the expansion of the universe. Longer wavelengths correspond to lower energy. Where did the photon’s energy go? Because time symmetry is broken in the universe, the energy of the photon is under no obligation to remain constant over such timescales. Deal with it, the universe says.

On timescales relevant to human activities, conservation of energy is extremely reliable. One way to put this is that the universe is 13.8 billion years old, or just over 1010 years. So in the course of a year, physics would allow an energy change by one part in 1010, or in the tenth decimal place. Generally, this is beyond our ability to distinguish, in practical circumstances.

But violations are even more restricted than that. A photon streaming across the universe is in the grip of cosmic expansion and bears witness to associated energy changes. But a deposit of oil lying underground for 100 million years is chemically bound and not “grabbable” by universal expansion, so is not “degraded” by cosmic expansion. In the end, while we acknowledge that energy conservation is not strictly obeyed in our universe, it might as well be for all practical purposes. Thus, this section amounts to a tiny asterisk or caveat on the statement that energy is always conserved.

D.3.2Convoluted Conservation¶

This section follows a chain of energy conversions that starts before our own Sun was formed, and ends in a car wreck as a way to flesh out the manner in which energy is conserved, in practice. Don’t worry about understanding every step, but absorb the overall theme that energy is changing from one form to the other throughout the process.

A gas cloud in space collapses due to gravitational attraction, exchanging gravitational potential energy into kinetic energy as the gas particles race toward the center of the cloud. The cloud collapses into a tight ball and all that kinetic energy in the gas particles “thermalizes” through collisions,2 generating a hot ball of gas that is to become a star. As the ball of gas contracts more, additional gravitational potential energy is exchanged for thermal energy as the proto-star gets hotter.Eventually, particles in the core of the about-to-be star are moving so fast as they heat up that the electrical potential barrier3 is overcome so that protons can get close enough for the strong nuclear force to take over and permit nuclear fusion to occur, at which point we can call this thing a star. Four protons4 bond together, two of which convert to neutrons 4: . . . hydrogen nuclei to form a helium nucleus. The total mass of the result is less than the summed mass of the inputs, the balance5 5: . . . via 퐸 = 푚푐2 going into photons, or light ; see Sec. 15.3 (p. 246) energy.

The photons eventually make it out of the opaque plasma of the star, and stream toward Earth, where a leaf absorbs the energy and cleverly converts it to chemical energy by rearranging atoms and electrons into sugars.6 The leaf falls off and eventually settles at the bottom of a shallow sea to be buried by sediments and ultimately becomes oil, preserving most7 of its chemical energy as it changes molecular form.

6: We call this photo 7: To the extent that of these exchanges- efficiency—we shou missing energy just2: Thermal energy is nothing more than kinetic energy—fast motion—of individual particles at the microscopic scale. Thermalizing means transferring energy into heat, or into randomized kinetic energy of particles in the medium.

3: . . . charge repulsion of two protons as their collision course brings them close to each other

4: ...hydrogen nuclei

5: ... via ; see Sec. 15.3 (p. 246)#### 6: We call this photosynthesis.

7: To the extent that energy is “lost” in any of these exchanges—operating at < 100% efficiency—we should recognize that the missing energy just flows into other paths,

One day, a silly human digs up the oil and combusts it with oxygen, converting chemical energy to thermal energy in a contained fireball explosion. The thermal energy is used to produce kinetic energy of a piston in a cylinder, transmitted mechanically to wheels that in turn propel a car along a freeway.8 8: . . . kinetic energy

The car climbs a mountain, converting chemical energy in the fuel into gravitational potential energy via the same thermal-to-mechanical chain described above. Along the way, kinetic energy is given to the air, thermal energy is given to the environment by the hot engine, and brakes get hot as the kinetic energy of the car is converted to heat via friction as the car comes to a stop. But the car does not fully stop in time before tipping over a cliff and giving up its gravitational potential energy to kinetic energy as the car plummets and picks up speed.

At the bottom, the crunch of the car ends up in bent metal9 and heat. 9: . . . a form of electric potential energy It does not explode, since this is not a movie. All the heat that was generated along the way ends up radiating to space as infrared radiation (photons), to stream across empty space—probably for all eternity.

Tracing the energy we use for transportation back far enough, passes through oil, photosynthesis, sunlight, and nuclear fusion in the sun’s core. Going back further, we recognize nuclear energy as deriving from gravitational energy of the collapsing material. What gave the atoms in the universe gravitational potential energy? The answer would have to be the Big Bang, truly arriving at the end (beginning) of the story.

D.3.3Lost to Heat¶

The sequence in Section D.2.2 terminated in heat and infrared radiation. But let’s flesh this out a bit, as heat is an almost-universal “endpoint” for energy flows.

Since energy is conserved, whatever goes to heat does not truly disappear: the energy is still quantifiable, measurable energy. It is considered to be “low grade” energy because it is hard to make it do anything useful, unless the resulting temperature is significantly different from the surroundings. Sec. 6.4 (p. 88) discusses notable exceptions, wherein we derive substantial useful work from thermal energy in heat engines. For now, we just note that it is entropy that limits the use of thermal energy.

When a book slides across a floor, it gives up its kinetic energy to heat caused by friction in the floor–book interface. When a car applies brakes and comes to a stop, a very similar process heats the brake pads and rotors. As a car speeds down the road, it stirs the air and also experiences friction in the axle/bearings and in the constant deformation of the tire as its round shape flattens on the road continuously. The stirred air swirls around in eddies that break up into progressively smaller ones

8: ...kinetic energy

9: ... a form of electric potential energy

10 10: In this way, we can make an explosion or fireball do useful work as in dynamite, internal combustion, or a coal-fired power plant.

until at the millimeter scale viscosity (friction) turns even this kinetic motion into randomized motion (heat).

Human metabolism converts chemical energy from food into exportable mechanical work (lifting, moving, digging, etc.) at an efficiency of 20– 25%. The rest is heat, which is conveniently used to maintain body temperature in most environments. But even most of the external work performed ends up as heat. The primary exception may be lifting masses to a higher location. Even this is temporary in the very long run,11 11: The “shelf” we place the mass on evenand the stored energy will ultimately flow into heat.

Light from our artificial sources and screens survives for a few nanoseconds as photon energy, but eventually is absorbed onto surfaces and turns to heat. Some small fraction of our light escapes to space and carries non-thermal energy away, but this is incidental and could be said to represent poor design (not putting light where it is useful).

Even devices whose job it is to cool things are net generators of heat. The air pushed out the back and bottom of a refrigerator is warm, as is the exhaust from an air conditioning unit. Virtually all energy pulled out of an electrical wall socket ends up as heat in the room in some way or another. A fan actually deposits a little bit of energy (heat) into the room, but feels cool to us only because the moving air enhances evaporation of water from our skin (perspiration), carrying energy away.

Essentially the only exceptions to the heat fate of our energy expenditures is anything that we launch into space, like electromagnetic radiation (radio, light). This is a very tiny fraction of our energy expenditure, and can be quantitatively ignored. Most of our energy is from burning fossil fuels, which is an inherently thermal process. The part we salvage as useful energy itself tends to end up as heat after serving its intended purpose.

In the end, most of the heat we generate on Earth’s surface finds its way back to space as infrared radiation. All objects glow in the infrared, and once the radiation escapes our atmosphere it is gone from Earth forever.12 At this point, the energy is pretty well spent, so that we would not be able to profit from its use should we try to capture it.13 The energy that came from the universe returns there, as part of the dull, fading glow that lingers from the Big Bang.

D.4Electrified Transport¶

This section aims to answer the question: Why can’t we just14 electrify transportation and be done with fossil fuels? It turns out to be hard. Rather then rely on external studies, this section applies lessons from the book to demonstrate the power of first-principles quantitative assessment. 14: ... beware of the word “just,” often hiding lack of familiaritytually collapses or is otherwise disturbed.

12: . . . except for some improbable paths that reflect off the moon, for instance, and return to Earth

13: The temperature of the radiating entities is so close to ambient temperature that its efficiency to perform useful work would be nearly zero.

ing lack of familiarity

Box 13.3 (p. 212) indicated that direct drive of cars and airplanes from solar energy is impractical: while it may work in limited applications, solar power is too diffuse to power air and car travel as we know it.

Thus electrified transport becomes all about storage, generally in batteries. Several times in the book, the energy density of gasoline was compared to that of battery storage. In rough numbers, gasoline delivers about 11 kcal/g, working out to ∼13 kWh/kg in units that will be useful to this discussion. Meanwhile, lithium-ion batteries characteristic of those found in cars15 15: The larger Tesla battery pack, for inhave energy densities about one-hundred times smaller.

This section will use the most optimistic energy density for lithium-ion batteries—around 0.2 kWh/kg—which is about 65 times less than for gasoline. Offsetting this somewhat is the fact that electric drive can be as high as 90% efficient at delivering stored energy into mechanical energy, while the thermal conversion of fossil energy in large vehicles is more typically 25%. The net effect is roughly a factor of twenty16 16: The math goes: 13 kWh/kg divided by difference in delivered energy per kilogram of fuel vs. storage.

The enormous mismatch in energy density between liquid fossil fuels and battery storage is the crux of the problem for transportation, the implications of which are explored here. We will start at the hard end, and work toward the easier.

D.4.0.0.1D.3.1 Airplanes¶

Box 17.1 (p. 290) already did the work to evaluate the feasibility of powering typical passenger planes electrically. The result was a reduction in range by a factor of 20, consistent with the premise above: the best lithium-ion technology—not yet achieved in mass-market—at 90% efficiency delivers about 5% as much mechanical energy per kilogram as do liquid fossil fuels.

Keeping the same 15 ton17 “fuel” mass, but now at 0.2 kWh/kg results in a 3,000 kWh battery capacity. The factor-of-twenty energy reduction per mass results in ranges down from 4,000 km via jet fuel to 200 km on battery, which is a two-hour drive, effectively. Charging a 3,000 kWh battery in the 30 minutes it typically takes for a plane to turn around—in efficient operations, anyway—would consume 6,000 kW, or 6 MW of power, which is about the same as the average electricity consumption of 5,000 homes.

17: One metric ton is 1,000 kg, and is often spelled tonne. Here, ton is used to mean metric ton, which is only 10% larger than the Imperial "short ton."We will keep track of kWh per kilometer as a useful metric for transportation efficiency, putting it all together at the end (Section D.3.7). In the case of air travel, it’s 3,000 kWh to go 200 km, or 15 kWh/km. On a per-passenger basis, 150 passengers in the airplane results in 0.1 kWh/km/person.

stance, provides 265 miles (425 km) of range and holds 85 kWh at a mass of 540 kg for an energy density of 0.16 kWh/g.

0.2 kWh/kg times 0.25/0.90, yielding a factor of 18. For the sake of estimation, 18 is close enough to a factor of 20 to use the more convenient and memorable 20× scaling factor in what follows.

spelled tonne. Here, ton is used to mean metric ton, which is only 10% larger than the Imperial “short ton.”

D.5D.3.2 Shipping¶

Large container ships ply the seas carrying stacks of shipping containers over very long stretches of open ocean. A typical ship operating between Shanghai and Los Angeles travels 10,400 km carrying 10,000 20-foot equivalent18 18: . . . TEU: 20-ft-equivalent units containers each bearing an average of something like 10 tons of cargo. Thus, the full (maximum) load is 100,000 tons.19 19: . . . called DWT: dead-weight tonnage

At normal cruising speed, the ship takes 10 days to make the journey, consuming about 325 tons of fuel per day. A battery large enough to replace 3,250 tons of fuel would be 20 times more massive, at 65,000 tons, displacing two-thirds of the cargo capacity, and requiring triple the number of ships to carry the same cargo. The resulting 13,000,000 kWh of storage20 20: This is 13 GWh, which would take the to travel 10,000 km results in 1,300 kWh/km.

The open ocean has no refueling stations. Even a refueling ship/platform would have to get the electrical energy from somewhere. Thus, shipping would be radically changed if electrified. Electric ships may not be able to cross open ocean, instead hugging the coast dotted with power plants21 21: . . . and from what source do they get ento supply frequent and lengthy charge stops for the ships.

D.6D.3.3 Long-haul trucking¶

Typical “big rigs” on the highway achieve a fuel economy around 6 miles per gallon (40 L/100 km) of fuel, while the most aerodynamic ones achieve 8 mpg (30 L/100 km). Long haul rigs carry two fuel tanks, each holding about 150 gallons (570 L; 425 kg). The range for the more efficient trucks therefore becomes about 2,000 miles (3,200 km).22 Cargo capacity is about 20 tons. 22: ... not using 100% of capacity to leave some prudent reserveTotal fuel mass is 300 gal times 2.85 kg/gal,23 or about 850 kg. The same mass of battery would hold 170 kWh and deliver a range of 100 miles (160 km; roughly 1 kWh/km). Ugh. Lots of recharging stops.23: ... density, in unusual units; equivalent to ~0.75 kg/LBut wait, trucks are big, right? Surely a larger battery can be accommodated. Unlike airplanes, where mass is critical, trucks can afford to pack on a larger battery. Some of the cargo space could be devoted to energy storage, surely. What fraction of the space would be acceptable?

To achieve comparable range as is presently realized, the battery mass would need to be about 20 times the gasoline mass, or 17,000 kg. Oh dear—the maximum cargo load was about 20 tons. So 85% of the cargo capacity is taken up by battery, which would seem to be unacceptable.

A solution would be smaller batteries and more frequent charging stops—possibly in the form of forklift-loaded pre-charged modules that are owned by the trucking company and can be interchanged among the fleet. Otherwise a substantial fraction of time would be spent charging: very possibly more time than is spent driving.

18: ... TEU: 20-ft-equivalent units

19: . . . called DWT: dead-weight tonnage

equivalent of an entire 1 GW power plant 13 hours to charge—or longer considering imperfect charge efficiency.

ergy? . . . picturing outposts on the remote Aleutian Islands

some prudent reserve

to ∼0.75 kg/L

It is not impossible24 to electrify long-haul trucking, but neither is it free of significant challenges. Certainly it is not as easy and convenient as fossil fuels.

24: Indeed, Tesla offers a Semi capable of#### D.3.4 Buses

Like cargo ships and long-haul trucks, public transit buses are on the go much of the time, favoring solutions that can drive all day and charge overnight. Given the stops and breaks, a typical bus may average 30 km/hour and run 14 hours per day for a daily range of approximately 400 km. At an average fuel economy of 3.5 mpg (70 L/100 km), each day requires about 300 L or 220 kg of fuel—no problem for a fuel tank. The equivalent battery would need to be 4,500 kg (900 kWh; 2.3 kWh/km), occupying about three cubic meters. Size itself is not a problem: the roof of the bus could spread out a 0.15 m high pack covering a 2 m × 10 m patch. Buses typically are 10–15 tons, so adding 4.4 tons in battery is not a killer.

Electrified transit is therefore in the feasible/practical camp. What makes it so—unlike the previous examples—is slow travel, modest daily ranges, and the ability to recharge overnight. Raw range efficiency is low, at 2.3 kWh/km, but this drops to a more respectable 0.2 kWh/km per person for an average occupancy of 10 riders.

For charging overnight, a metropolitan transit system running 50 routes and 8 buses per route25 and therefore needs to charge 400 buses over 6 hours at an average rate of 150 kW per bus26 for a total demand of 60 MW—equivalent to the electricity demand of about 50,000 homes.

D.7D.3.5 Passenger Cars¶

Passenger cars are definitely feasible and practical for some uses. Typically achieving 0.15–0.20 kWh/km, the average American car driving 12,000 miles per year (about 50 km/day, on average) would need at least 10 kWh capacity to satisfy average daily driving, but would need closer to 100 kWh to match typical ∼500 km ranges of gasoline cars.

At a current typical cost of $200–300 per kWh, such a battery costs $20,000 to $30,000, without the car.27 The most basic home charger runs double the price. at 120 V and 12 A,28 multiplying to 1,440 W. A 100 kWh battery actually takes closer to 110–120 kWh of input due to 80–90% charge efficiency. Dividing 115 kWh by 1.44 kW leaves 80 hours29 29: . . . 3.3 days! as the charge time. Table D.1 provides similar details for this and two other higher-power scenarios.

The middle row of Table D.1 is most typical for home chargers and those found in parking lot charge stations, resulting in an effective charge speed of about 10 miles per hour, or 16 km/hr. This is a convenient way to 500 mile range, but see this careful analysis [129] on the hardships.

25: A one-hour one-way route operating on a 15 minute schedule needs 4 buses in service in each direction of the route, for instance.

26: . . . 900 kWh capacity and 6 hours to charge

27: Thus, long-range electric cars roughly

28: . . . satisfying the 80% safety limit for a 15 A circuit

29: . . . 3.3 days!

| Volts | Amps | circuit | kW | hours | mi/hr | km/hr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 | 12 | 15 A | 1.44 | 80 | 4 | 6 |

| 240 | 16 | 20 A | 3.8 | 30 | 10 | 16 |

| 240 | 40 | 50 A | 9.6 | 12 | 25 | 40 |

characterize charge times. Adding enough charge to cover an average day of 30 miles or 50 km will take about 3 hours for the middle-row case, or just over an hour for the high-power charge.

Imagine now making a long road trip, driving at 100 km per hour. Even the fastest charge rate30 in Table D.1 is 2.5 times slower. Every 400 km driven will take 4 hours on the road plus 10 hours at a charger for an average rate of 28 km/hr,31 or 18 mi/hr.

30: ... which is much high parking lot chargers that a with the middle row

31: ... 400 km in 14 hoursSpecial fast-charge stations can provide a staggering 250 kW32 of power, 32: . . . like 200 homes cutting charge times dramatically. But this is neighborhood-scale energy delivery that households cannot expect to supply themselves. It is also informative to compute the temperature rise of a battery from a fast charge. If charging is 90% efficient, the other 10% turns to heat in the battery. Each kilowatt-hour of battery capacity has an associated mass around 5–10 kg, and receives 0.1 kWh (360 kJ) of thermal energy when charged. At a specific heat capacity around 1,000 J/kg/◦C, a 360 kJ deposition increases the cell’s temperature by 36–72◦C, depending on energy density.33 33: . . . higher energy density (better) batter-This is not a small rise (reaching boiling temperatures on warm days), and can contribute to shorter battery lifetime.

So electric cars are not simple drop-in replacements for the gasoline machines roaming the roads today, that effectively refuel at a rate of 10 MW34 given the fast delivery of an extremely energy-dense liquid. On performance and convenience measures, it would be hard to characterize them as superior substitutes. But they can certainly suit well for local travel when given ample time to recharge—overnight, for instance. And in the long run, it seems we will have little choice.

34: . . . the equivalent electricity consump-For all this, several things still are not clear:

- Will large scale ownership of electric cars become affordable, or remain cost prohibitive? Battery prices will surely fall, but enough?

- If widespread, how will residential areas cope with tremendous increases in electrical demand during popular recharge hours?

- How could night-time charging utilize solar input?

- Will enough people willingly give up long-range driving capability? Will dual-system cars (like plug-in hybrids) be preferred to maintain gas capability for the occasional longer trip?

- Will people sour over costly battery decline and replacement?

Electric cars are a growing part of transportation, and will no doubt grow more. It is too early to tell whether they will be able to displace fossil cars in the intermediate term. If not, personal transportation is likely to decline as fossil fuel use inevitably tapers away.

Table D.1: Approximate charge times and effective speeds (in miles per hour and kilometers per hour) for charging a 100 kWh battery at three different household power options. Such a battery delivers a range of about 300 miles, or 500 km.

30: . . . which is much higher than typical parking lot chargers that are more in line with the middle row

31: . . . 400 km in 14 hours

32: ...like 200 homes

ies will experience a larger temperature rise based on less mass to heat up per amount of energy injected

tion of 10,000 homes or a medium-sized college campus

D.7.0.0.1D.3.6 Wired Systems¶

To finalize the progression of hardest–to–easiest electrified transportation, we leave the problematic element behind: batteries. Vehicles on prescribed routes (trains, buses) can take advantage of wires carrying electricity: either overhead or tucked into a “third rail” on the ground. Most light rail systems use this approach, and some cities have wires over their streets for trolley buses. High-speed trains also tend to be driven electrically, via overhead lines.

The ease with which wired electrical transport is implemented35 relative to the other modes discussed in this Appendix is another way to emphasize the degree to which storage is the bottleneck.

35: Wired electrified transport has been a#### D.3.7 Collected Efficiencies

Each transportation mode in the previous sections reported an efficiency, in terms of kilowatt-hours per kilometer. Not surprisingly, mass and speed play a role, making container ships very hard indeed to push along, followed by airplanes. In some cases, it makes sense to express on a per-passenger or per-ton basis, distributing the energy share among its beneficiaries. Table D.2 summarizes the results, sometimes offering multiple options for vehicle occupancy to allow more fruitful comparisons among modes. Note that air travel looks pretty good until realizing that the distances involved are often quite large, making total energy expenditure substantial for air travel.

| Mode | context | kWh/km | load | kWh/km/unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ship | cargo | 1,300 | 100 kton | ∼0.01/ton |

| Air | passenger cargo | 15 | 150 ppl 15 ton | 0.1/psn 1/ton |

| Bus | passenger passenger | 2.3 | 10 ppl 30 ppl | ∼0.2/psn ∼0.07/psn |

| Truck | cargo | ∼1 | 20 ton | 0.05/ton |

| Car | passenger passenger | 0.18 | 1 psn 2 ppl | ∼0.18/psn ∼0.09/psn |

steady contributor to transportation for over a century.

Table D.2: Energy requirements for various modes of transportation (lower numbers are more efficient). Total energy is distance times the measure in kWh/km. Loads are expressed contextually either as people (ppl) or tons (1000 kg). Per-passenger/ton efficiency depends on occupancy—expressed as kWh/km per person (psn)—for which multiple instances are offered in some cases. While trucks have a far better kWh/km measure than ships, ships are about four times more efficient per ton, carrying 5,000 times more cargo. Air freight is 100 times more energetically costly than by ship!

D.8D.4 Pushing Out the Moon¶

Some forms of alternative energy are tagged with asterisks in Table 10.1 (p.166), indicating that they are not technically renewable, but will last a very long time so might as well be considered to be renewable.

Tidal energy, covered in Sec. 16.2 (p. 280), is one such entry that honestly does not deserve much attention. The text mentioned in passing that

aggressive use of tidal energy has the power to push the moon away from Earth, providing the mechanism by which we could “use up” this resource. Curious students demanded an explanation. Even though it’s not of any practical importance, the physics is neat enough that the explanation can at least go in an appendix.

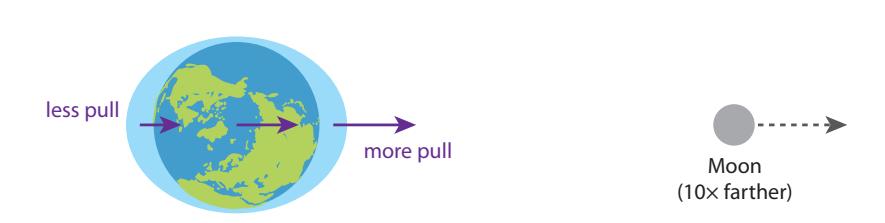

The first step is realizing that Earth and Moon each pull on each other36 via 36: In fact, equally, per Newton’s third law. gravitation. Since the strength of gravity decreases in proportion to the square of the distance between objects, the side of the earth closest to the moon is pulled more strongly than the center of the earth, and the side opposite the moon is pulled less strongly. The result is an elongation of the earth into a bulge—mostly manifested in the oceans (Figure D.1).

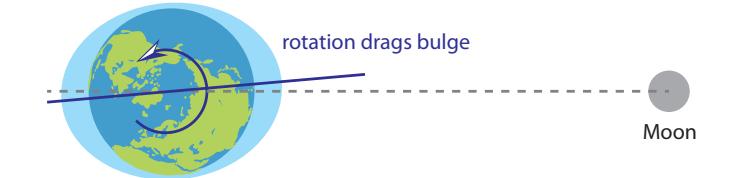

The second step is to appreciate that the earth rotates “underneath” the moon, so that the bulge—pointing at the moon—is not locked in place relative to continents.37 But friction between land and water “drag” the bulge around, very slightly rotating the bulge to point a little ahead38 of the moon’s position (Figure D.2).

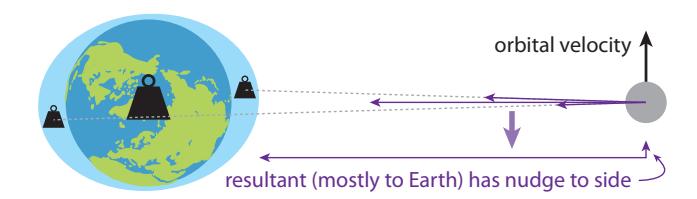

Now think about how the moon sees the earth, gravitationally. It mostly sees a spherical earth, but also a bulge on the front side, slightly displaced, and a bulge on the back side, also displaced in the opposite direction (Figure D.3). While the bulge masses are equal, the closer one has a greater gravitational influence and acts to pull the moon a little forward in its orbit, speeding it up.39

Accelerating an orbiting object along its trajectory adds energy to the orbit and allows the object to “climb” a little farther away from the Figure D.1: The moon pulls harder on the near side of the earth, and less hard on the back side. Relative to the earth as a whole (medium force), the near side advances toward the moon and the back side lags the rest of the earth, creating a bulge on both sides that is aligned toward the moon. Note that a drawing to scale would put the moon well off the page.

36: In fact, equally, per Newton’s third law.

Figure D.2: The rotation of Earth and it continents “underneath” the tidal bulge creates a friction, or drag, that pulls the bulge around a few degrees (somewhat exaggerated here), so that it no longer points directly at the moon.

37: This is why we experience two high tides per day and two low tides: the earth is spinning underneath the opposite bulges, so that a site on the surface passes under a bulge (high tide) every ∼ 12 hours.

38: The angular shift is around 1–2°.Figure D.3: Gravitationally, the earth looks like a big central mass and two bulge masses displaced from the connecting line. The closer mass pulls harder than the more distant one, so the addition of all the force vectors (not to scale) results in a little asymmetry, leaving a small sideways component of the force along the same direction as the moon’s orbital velocity (up in this drawing).

39: It may help to think of this bulge as being like a carrot dangled in front of a horse, encouraging it forward.

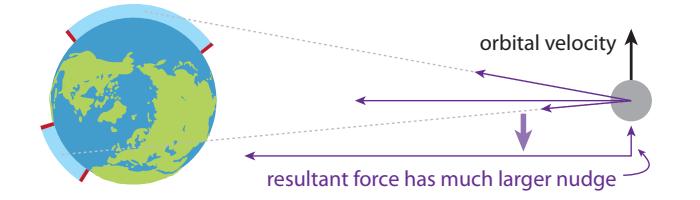

central body. So this displaced tidal bulge on Earth is tugging the moon forward and causing it to climb about 3.8 cm per year away from Earth. That’s one-ten-billionth of its orbital radius per year, so it’s not going away for a very long time, indeed.40

If we built global-scale structures (Figure D.4) to capture tidal energy in a big way,41 we would effectively increase the lag angle of the tidal bulge. This is because we would likely release the captured stack of water over a period of many hours,42 rotating this stack of water around the planet farther than it would naturally go. Now the gravitational pull in the forward direction would increase and the egress would speed up. If we managed to extract 18 TW43 out of tides, this would be six times larger than the current 3 TW of tidal dissipation, and we might expect the egress to increase to about 23 cm per year.It’s still a slow rate, and would not drive the moon away faster than hundreds of millions of years. So technically tidal energy is a onetime resource whose use diminishes its long term capacity.44 But the 44: This is why it is not strictly renewable timescales are so ridiculously long that we may as well think of tidal energy as inexhaustible.

D.9D.5 The Long View for Humanity¶

Sec. 8.1 (p.114) took a sweeping view of humanity’s timeline as a useful lens through which to appreciate the very short age during which fossil fuels impart a substantial energy benefit. This section revisits this timewarping perspective in a slightly different way as a means to reflect on humanity’s far future.

D.9.0.0.1D.5.1 Success vs. Failure¶

We start by noting that human civilization is about 10,000 years old, to the nearest order-of-magnitude.45 45: This roughly marks the start of agri-Consider this question:

Is human civilization still in its infancy, or are we closer to the end than the beginning?

Wow. Heavy question. Of course, we do not know the answer, but most of us would prefer to believe the first—that we are only beginning. So let’s roll with that and explore the consequences.

40: All the same, total solar eclipses will no longer occur after several hundred million years because the moon will be farther and too small to entirely block the sun.

Figure D.4: If we built some inconceivable global-scale tidal capture structure the size of oceans and let them drain for six hours or so, the artificial bulges we created would travel farther around with the earth’s rotation, enhancing the sideways “kick” and encouraging the moon to climb away from earth at a faster rate.

truly ludicrous idea plagued by a giant list of practical problems, and all for such a small gain.

42: . . . like the ∼6 hours between high tide and the next low-to-high tide cycle

43: . . . our current energy scale; not feasible, but used to illustrate

44: This is why it is not strictly renewable

culture, and in any case is far closer to the truth than the adjacent order-of-magnitude figures of 1,000 years or 100,000 years.

In order for human civilization to be in its infancy, it would have to continue for at least 10,000 years more, if not far longer. What would it mean for us to still be operating “successfully” 10,000 years from now? Our physics and math approach actually allows us to place constraints!

This discussion is limited to living on Earth. Chapter 4 laid out reasons why imagining a space-faring future may be misguided. But even ignoring these arguments, Chapter 1 illustrated that human growth ambitions would be brought to an end long before 10,000 years pass. In this light, it is most straightforward to concentrate on what it would take to succeed on Earth itself.46

If we manage to carry our civilization into the far future,47 we can comfortably call this success. If we don’t, well, that would be failure. Can we sketch out what success looks like? One easy way to get there is to start enumerating the things that can’t be carried into the far future.- 1. Fossil fuels will not power civilization: a large fraction of the initial inheritance has been spent in a short 200 years,48 so that 10,000 48: . . . most of this in the last 50 years years in the future it is safe to say they will be long gone.

- No steady annual decline of natural resources like forests, fisheries, fresh water, or species populations can be brooked. Allowing any component to decline would mean eventually losing that resource, which may be critical to our survival.

- Human population will not be allowed to grow. Even small growth rates will step up pressure on natural resources, and Earth can only support so much, long-term. Independent of what the “right” number is,49 49: . . . unlikely as high as 10 billion, and once settled, we will not be able to dial it up without imperiling the hard-won success.

- Even under steady human population, any increase in resource use per person will also not be compatible. In general, growth leads to a dead end: to failure.

- Mining materials from the Earth will not continue at anything near the current pace. In the last few hundred years, the best deposits of copper, gold, aluminum, etc. have been found and exploited. Even if only 10% of the attainable resource has been consumed thus far,50 50: . . . author’s conjecture; it could well be continuing for tens of thousands of years (and beyond) cannot be expected.

- Ultimately, any activity that draws down a finite natural resource will be impossible to sustain if the extraction rate is modest or high in relation to the initial resource abundance. Anything that can’t last for well over 10,000 years is not a viable long-term solution and should not be exploited if success is the goal. Likewise, any pollutant that can build up to dangerous levels on even these very long timescales cannot be tolerated, if failure is to be avoided.

- We can use the rule of 70 to say that anything having a doubling time (or halving-time in the case of depletion) shorter than 10,000 years is a no-go for success on these timescales, meaning that any activity impacting resources would have to be held to a growth rate

46: Even if extending to other planets, the same logic will apply.

rupted preservation of the knowledge and history gained thus far, without some apocalyptic collapse forcing a start-from-scratch revival—to the extent that’s even plausible.

48: ... most of this in the last 50 years

it could even be well less than a billion, depending on living standards

higher

or depletion rate of less than 0.007% per year, which is essentially zero-growth.

It becomes clear that long-term success is practically synonymous with the word sustainable. Any practice that is not long-term sustainable will fail to continue.51 51: Any activity today not geared to con-We therefore cannot depend on any non-sustainable resource if we strive for success.

D.9.0.1D.5.2 Sustainable Living¶

Imagine that you have a stash of $100,000 tucked under your mattress, and that you have figured out a way to live on $20,000 per year. You could decide to live on this fund for five years, and then figure out later how to keep going. Perhaps this is not the wisest move. A smarter move would be to figure out how long you expect to live—maybe 50 more years—and ration out the fund, allowing $2,000 per year. You’ll still need a job earning $18,000 per year to meet the $20,000 annual goal. Maybe the smartest move would be to ignore the money under the mattress and get a job for $20,000 per year.52 Now you have the safety of resources should you need it, and can even pass it along down the generations to kids and grandkids who have also been taught not to use it, but to survive on their annual income.

The analogy is clear, and perhaps it is also clear why we did not allow interest accumulation, as many of Earth’s resources are one-time endowments that do not spontaneously grow larger.53 53: Interest is an artificial construct made If our human civilization succeeds at surviving uninterrupted for 10,000 years, it will necessarily be because we figured out how to live on the annual income54 54: Annual income would be in the form of provided by Earth’s natural renewable flows, rather than on the inheritance in the form of finite resources that are not replenished. In other words, humanity needs to learn to refrain from any dependence on one-time resources (the inheritance).Success, therefore, puts humans as a part of nature, not apart from nature. Anything else is failure. The closer we are to nature, the more likely we are to succeed.

Nature prepared a biosphere that has stood the test of time. Natural selection has operated to eliminate non-viable solutions and create interdependencies cleverly balanced in a stable equilibrium of sorts. Elements of modern human civilization—our cities, agricultural practices, fossil fuel dependence—have not withstood the test of time, nor can they. Which system would be the wiser bet for long-term survival: the well adapted natural world, or the artificial world humans have erected and operated for a few dozen decades—without attention to sustainable principles? The answer seems obvious.

tribute to ultimate success (true sustainability) is therefore likely only contributing to failure. Most activities today are in the latter category, alarmingly.

year, so if you’re going this far already, why not?

possble by accelerating resource use.

solar energy delivered and biomass that has grown in the course of the year, for instance.

D.10D.5.3 Time to Grow Up¶

In a sense, humanity is going through an awkward adolescent phase: growth spurts, a factory (pimple) strewn landscape, an attitude that we have all the answers—adults55 can’t possibly understand or tell us what to do. Conversely, nature is mature.56 Ignoring recent human influences, it had already forged its complex, never perfect, but functional interdependencies and had settled into something resembling a steady state. Adolescents new to the scene may be hugely disruptive and destructive, and unless they change their ways, civilization drives straight into the jaws of failure. The adolescents lack the wisdom to build lasting systems that will have the privilege of co-existing with nature for very long.In human society, most adolescents become adults who learn to live within their means. Sometimes this involves sacrifices or perhaps selecting a diet based on nutrition and health rather than what might be most tasty.57 57: . . . opting out of the plan to eat ice cream Likewise, humankind needs to define a scale for its activities that fits within nature’s capacity to replenish, so that each subsequent generation is not deprived of resources the previous ones enjoyed. At present, civilization is nowhere close to this operating principle.

D.11D.5.4 Frameworks¶

Humanity needs to develop a framework by which to evaluate its activities and ask whether each helps or hurts ultimate human success. Sometimes this might produce jarring results. Consider, for instance, a cure for cancer or other advances that might extend human lifetimes. Only if balanced against a smaller population or a smaller resource utilization per capita could such seemingly positive developments be accommodated once a steady equilibrium is established. Otherwise, total demand on Earth’s resources goes up if the same number of people live longer at a fixed annual resource utilization per living person. In a successful world, any proposed new activity would have to demonstrate how it fits within a sustainable framework. Ignoring the issue would irresponsibly imperil overall long-term human happiness.58 58: In such cases, the outcome may ulti-

At some level, humans need to realize that success means the thriving of ple. not only themselves, but all of Earth’s precious irreplaceable species and ecosystems. Without them, humans cannot be successful anyway. This is another part of maturing: many adolescents have difficulty considering the impacts of their actions on anyone other than themselves. Humans need to realize that hurting any component of Earth is hurting humans, long-term. Our legal system affords rights to humans, but gives no agency to plants, animals, or even non-living features of our planet. A successful future must give voice to every element of our world, lest we trample it and rue the day.

55: . . . in this case hypothetical wise humans who have managed a successful transition through the adolescent phase

56: Note the similarity of the words!

for dinner

mately settle on longer lives for fewer peo-

Can it work? Can humans create the institutions and uncorrupted global authority to regulate the entire biosphere—or at least the human interface—to prevent unsustainable disruption to the rest? Is human nature compatible with such schemes? Do we have the discipline to deny ourselves easily reached resources for the good of the whole? Individual desires for “more” may always work to subvert sustainable practices. Individual lifetimes are so very short compared to the necessarily longterm considerations of success that it will be very hard to universally accept seemingly artificial restrictions generation after generation. Also unclear is whether it is possible to maintain a technological society preserving knowledge and history while living on the annual renewable resources of the planet. We simply have no guiding precedent for that mode of human existence.

It is therefore an open question whether a technological society is even compatible with planetary limits. Are modern humans just a passing phase whose creations will crumble into oblivion in a geological blink, or can we stick it out in something other than a primitive state? We again have no evidence59 59: See Sec. 18.4 (p. 312) on the Fermi paraone way or another. The current state of apparent success cannot be taken as a meaningful proof-of-concept, because it was achieved at the expense of finite resources in a shockingly short time: an extravagant party funded by the great one-time inheritance. The aftermath is only beginning to appear.

We have a choice: work toward success—hoping and assuming that it is indeed possible; or acquiesce to failure. It seems that if we are not wise enough to know whether long-term success is even possible, the responsible course of action would be to assume that we can succeed, and do what we can to maximize our chances of arriving there. When should we start? Again—without knowing any better—the sooner we start, the more likely we are to succeed. Any delay is another way of driving ourselves toward a more likely failure.

D.12D.6 Too Smart to Succeed?¶

This section pairs nicely with Section D.5, taking a slightly different perspective on the prospect of future success.

Evolution works incrementally by random experimentation: mutations that either confer advantages or disadvantages to the organism. Advantages are then naturally selected to propagate to future generations,60 60: After all, advantages make survival and while disadvantages are phased out by failure of afflicted organisms in procreation more likely. competition for resources and mates. Evolution is slow, and hard to spot from one generation to the next. When a common ancestor of the hippo evolved into whales, the nose did not suddenly disappear from the face to end up behind the head as a blow-hole, but took a tortuously long adaptive route to its present configuration.

dox for a worrisome—albeit inconclusive lack of evidence of success in the universe.

60: After all, advantages make survival and procreation more likely.

Intelligence confers obvious advantages61 to organisms, able to “out- smart” competition to find resources, evade dangers, and adapt to new situations. It also has some cost in terms of energy resources devoted to a larger brain. But multiple organisms from across the animal kingdom have taken advantage of the “smart” niche: octopuses, ravens, dolphins, and apes to name a few. Experiments reveal the ability of these species to solve novel, brainy puzzles in order to get at food, for instance.

61: Intelligence is not the only sort of ad- vantage, and can easily lose to tooth and claw, or even mindless microscopic threats: nature has devised many ways to “win.”Like other attributes, intelligence would not be expected to arrive suddenly, but would incrementally improve. Humans are justified in appraising themselves as the most intelligent being yet on the planet.

So here’s the thing. The first species smart enough to exploit fossil fuels will do so with reckless abandon. Evolution did not skip steps and create a wise being—despite the fact that the sapiens in our species name62 means wise. A wise being would recognize early on the damage inherent in profligate use of fossil fuels63 and would have refrained from unfettered exploitation.

62: ... self-assigned flattery

63: Not only is climate change a problem,Put another way, the first species entertaining the notion that they are able to outsmart nature is in for a surprise. Earth’s evolutionary web of life is dumb: it has no intelligence at all. But it exists in this universe on the strength of billions of years of tested success. All the random experiments along the way that were unworkable got weeded out. The vast majority of species around today have checked the box for long-term viability.

Modern humans—those who have moved beyond hunter-gatherer lifestyles, anyway—represent an exceedingly short-lived experiment in evolutionary terms. This is especially true for the fossil fuel era of the last few centuries. It would be premature to declare victory. The jury is still out on whether civilization is compatible with nature and planetary limits, as explored in Section D.5.

Evolution does not avoid mistakes. In fact, it is built upon and derives its awesome power precisely because of those few mistakes that somehow escape the more likely failed outcomes and find advantage in the mistake.64 64: Since mutations are random mistakes, Maybe humans are one of those more typical evolutionary mistakes that will culminate in the usual failure, as so often happens. The fact that we’re here and smart says nothing about our chances for long-term success. Indeed, humankind’s demonstrated ability to produce unintended global adverse consequences would suggest that success is less than a safe bet.

It seems fairly clear that hunter-gatherer humans could have continued essentially indefinitely on the planet. And the brains of hunter-gatherer Homo sapiens are indistinguishable from those of modern humans. So intelligence by itself is not enough to cross the line into existential peril, if continuing to operate within and as a part of natural ecosystems. But once that intelligence is applied toward creating artificial environments65 65: . . . e.g., agriculture, cities that no longer adhere to the ways of nature—once we make our own rules

vantage, and can easily lose to tooth and claw, or even mindless microscopic threats: nature has devised many ways to “win.”

but building an entire civilization dependent on a finite energy resource and also enabling a widespread degradation of natural ecosystems seems like an amateur blunder.

and some actually, surprisingly, turn out to be advantageous, one might say that life is a giant pile of mistakes that failed to deliver the expected bad outcomes, snatching success from the jaws of failure.

65: ... e.g., agriculture, cities

as we “outsmart” nature—we run a grave risk as nature and evolution cease to protect us. In other words, a species that lives completely within the relationships established by the same evolutionary pressures that created that species is operating on firm ground: well adapted and likely to succeed, having stood the test of time.66

Once we part ways with nature and create our own reality—our own rules—survival is no longer as guaranteed. Even 10,000 years is not enough time to prove the concept, when human evolution works on much longer timescales. This is especially true for the fossil fuel world, being mere centuries old. Nature will be patient while our fate unfolds.

The situation is similar to establishing a habitat on the lunar surface: an artificial environment to provision our survival in an otherwise deadly setting. The resources that were available to construct the habitat are not continually provided by the lunar environment, just as the fossil fuels and mined resources and forests are not continually re-supplied67 as we deplete them. Just because the habitat could be built does not mean it can be maintained indefinitely. Likewise, the world we know today—being rather different from anything that nature prepared—may be a one-off that proves to be unsustainable in the long run.

67: Forests can grow back, but not at the rate of their destruction at present.Since evolution is incremental, we cannot expect to have been made wise enough to avoid the pitfalls of being just smart enough to exploit planetary resources. And being slow, it seems unlikely that wisdom will evolve fast enough to interrupt our devastating shopping spree. It is possible68 that we can install an “artificial” wisdom by using our intelligence to adopt values and global rules by which to ensure a sustainable existence. Probably most smart people assume that we can do so. Maybe. But living in a collective is difficult. Wisdom may exist in a few individuals, but bringing the entire population around to enlightened, nuanced thinking that values nature and the far future more than they value themselves and the present seems like a stretch.

68: What hope we have lies here, and provides the underlying motivation for writing this book. The first step is appreciating in full the gravity of the challenge ahead.One way to frame the question:

Are humans collectively capable of leaving most shelves stocked with treats, within easy reach, while refraining from consuming them, generation after generation?

Do we have the discipline to value a distant and unknown future more than we value ourselves and our own time? Successful non-human species have never had to answer this question, but neither has any species been smart enough—until we came along—to develop the capability to steal all the goodies from the future and, in so doing, jeopardize their own success.69 69: Success here means preserving civiliza-

66: Since evolution is slow, any species has a reasonably long track record of success behind it.

rate of their destruction at present.

vides the underlying motivation for writing this book. The first step is appreciating in full the gravity of the challenge ahead.

tion. It is far easier—and perhaps more likely—to at least survive as a species in a more primitive, natural state.

D.13D.6.1 Evolution’s Biggest Blunder?¶

As a brief follow-on, we framed evolution as a mistake-machine, sometimes accidentally producing functionally advantageous incremental improvements. Countless species adapt in ways that are not able to survive long term, and die off. So those “blunders” are inconsequential failed experiments. Evolution is indifferent to failure, being a mechanism rather than a sentient entity.

But most of the time, these failures are isolated, bearing little consequence on the wider world. Did anybody notice the three-dotted bark slug70 70: . . . totally made up disappear? If the human species turns out to be another of evolution’s failed experiments—having made a creature too smart to stay within the lanes of nature—is it just another inconsequential blunder?

Unfortunately, it may turn out to be a rather costly blunder, if the failed species creates a mass extinction as part of its own failure. By changing the climate and habitat on the planet, we have already terminated or imperiled a number of species, and are nowhere near finished yet. Mass extinctions have happened many times through history, but seldom due to an evolutionary blunder. We may yet distinguish ourselves!

It is true that cyanobacteria transformed the climate starting about 2.5 billion years ago by pumping oxygen into the atmosphere. Called the Great Oxygenation Event, this precipitated the first-known mass extinction on the planet—essentially poisoning the simple anaerobic lifeforms that existed until that time. But we would hesitate to call it an unmitigated disaster, as it paved the way for multi-cellular life71 71: . . . although it took over a billion years the richness we see today. So accidental? Yes. Blunder? Okay. Disastrous? Let’s say no, on balance.72 72: The anaerobic life would disagree, but

The most recent mass extinction, 65 Myr ago, was caused by an asteroid impact, and the two before that appear to be connected to volcanic activity. The two prior to these are mixed: the first appears to have been caused by geological processes, and the next by a changing climate likely connected to diversification of land-based plants. And that’s it, since the much earlier cyanobacteria oxygenation event. Only one of the five is likely attributable to evolution itself—and in this case not the fault of a single species.

A human-caused mass extinction could pave the way to whole new modes of lifeforms. But it was much easier in the early days to break new ground. It seems much less likely that a human-induced mass extinction will unleash a fantastic evolutionary richness hitherto unexplored. That leaves only downside, and the ignominious distinction of being the one species that evolution would most regret, if ever it could.

Please, please, please—let this tragic fate not come to pass!

70: ... totally made up

to get there: no instant gratification in all

when do we ever listen to them anymore? In any case, the result was tremendous biodiversity, which ultimately may be a decent figure of merit for value in this world.