4.1Space Exploration vs. Colonization¶

This textbook assesses the challenges and limitations imposed upon us by living on a finite planet having finite resources. If harboring expectations that we will break out into a space-faring existence as a way to mitigate our earthly challenges, then it becomes harder for us to respond earnestly to information about where things are headed on Earth. This chapter is placed where it is to “close the exit” so that the content in the rest of the book might become more relevant and worth the investment to learn. Some of the sections in this chapter offer more of an author’s perspective than might be typical for a textbook. Some may disagree with the case that is made, but consider that the burden of proof for a way of life unfathomably beyond our current means should perhaps fall to the enthusiasts.1 1: To quote Carl Sagan, extraordinary

4.1.14.1 Scale of Space¶

In the span of two hours, we can sit through a movie and “participate” in interstellar travel without getting tired. Let’s step out of the entertainment (fiction) industry and come to terms with the physical scale of the real space environment.

Describing an analogous scale model of the solar system, galaxy, and universe—as we will do momentarily—is a fraught exercise, because in order to arrive at physical scales for which we have solid intuition (driving distance in a day?) we end up with inconceivably small (invisible) specks representing familiar objects like the earth. By the time we make Earth the size of something we can hold and admire, the scales become too big for easy comprehension. Figures 4.1 and 4.2 demonstrate how awkward or impossible correctly-scaled graphics are in a textbook.claims require extraordinary evidence.

it is used as a proper name, and refer to the earth when it is an object. Similar rules apply to Moon and Sun.

Photo credit: NASA/Bill Anders from Apollo 8 [22].

Figure 4.1: Earth and Moon (far right) to scale. On this scale, the sun would be larger than the page and about 400 pages away. Mars would be 160 to 1,100 pages away. Since 1972, humans have not traveled beyond the black outline of the earth in this figure (600 km).

4.2Sun Earth (invisible)¶

Figure 4.2: Proving the point that textbooks are not conducive to correctly-scaled graphics of objects in space, by the time the Earth-Sun distance spans the page, Earth (on far right) is too small to be visible in print, at less than 1% the diameter of the orange sun at far left. The Earth–Moon distance is about the width of the arrow shaft pointing to Earth. Humans have never traveled more than the arrow shaft’s width from Earth, and have not even gone 0.2% that far in about 50 years! Mars, on average, is farther from Earth than is the sun.

Let us first lay out some basic ratios that can help build suitable mental models at whatever scale we choose.

Definition 4.1.1 Scale models of the universe can be built based on these approximate relations, some of which appear in Table 4.1 and Table 4.2:

- 1. The moon’s diameter is one-quarter that of Earth, and located 30 earth-diameters (60 Earth-radii) away from Earth, on average (see Figure 4.1).

- 2. The sun’s diameter is about 100 times that of Earth, and 400 times as far as the moon from Earth (see Figure 4.2).

- 3. Mars’ diameter is about half that of Earth, and the distance from Earth ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 times the Earth–Sun distance.

- 4. Jupiter’s diameter is about 10 times larger than Earth’s and 10 times smaller than the sun’s; it is about 5 times farther from the sun than is the earth.

- 5. Neptune orbits the sun 30 times farther than does Earth.

- 6. The Oort cloud2 of the sun, gravitationally. of comets ranges from about 2,000 to 100,000 times the Earth–Sun distance from the sun.

- 7. The nearest star3 is 4.2 light years from us, compared to 500 lightseconds from Earth to the sun—a ratio of 270,000.

- 8. The Milky Way galaxy has its center about 25,000 light years away away,4 closest star. and is a disk about four times that size in diameter.

- 9. The next large galaxy5 5: . . . the Andromeda galaxy is 2.5 million light years away, or about 25 Milky Way diameters away.

- 10. The edge of the visible universe6 is 13.8 billion light years away, or about 6,000 times the distance to the Andromeda galaxy.

We will construct a model using the set of scale relations in Definition 4.1.1, starting local on a comfortable scale.

We’ll make Earth the size of a grain of sand (about 1 mm diameter). The moon is a smaller speck (dust?) and the diameter of its orbit would span the separation of your eyes. On this scale, the sun is 100 mm in diameter (a grapefruit) and about 12 meters away (40 feet). Mars could be anywhere from 4.5 meters (15 feet) to 30 meters (100 feet) away. Reflect

Table 4.1: Progression of scale factors.

| Step | Factor |

|---|---|

| Earth diameter | (start) |

| Moon distance | 30× |

| Sun distance | 400× |

| Neptune distance | 30× |

| Nearest Star | 9,000× |

| Milky Way Center | 6,000× |

| Andromeda Galaxy | 100× |

| Universe Edge | 6,000× |

2: The Oort cloud marks the outer influence

3: . . . Proxima Centauri

A light year is the distance light travels in a year.

4: That’s 6,000 times the distance to the

5: ...the Andromeda galaxy

6: The “edge” is limited by light travel time since the Big Bang (13.8 billion years ago), and is called our cosmic horizon. See Sec.D.1 (p. 392) for more.

As we build up our model, pause on each step to lock in a sense of the model: visualize it or even recreate it using objects around you!

| Body | Symbol | Approx. Radius | Distance (AU) | Alt. Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | — | |||

| Moon | ||||

| Sun | 1 | |||

| Mars | \male | 0.4–2.7 | ||

| Jupiter | 4–6 | |||

| Neptune | ||||

| Proxima Centauri | — | 270,000 | 4.2 light years |

for a second that humans have never ventured farther from Earth than the moon, at 3 cm (just over an inch) in this scale.7 Mars is outlandishly eye as the moon. farther. Neptune is about four-tenths of a kilometer away (on campus at this scale), and the next star is over 3,000 km (roughly San Diego to Atlanta). So we’ve already busted our easy intuitive reckoning and we haven’t even gotten past the first star. Furthermore, this was starting with the earth as a tiny grain of sand. We’ve only ever traveled twofinger-widths away from Earth on this scale,8 and the next star is like 8: The last time we went this far was 1972. going on a giant trip across the country. For apples-to-apples, compare how long it takes to walk a distance of two-finger-widths (3 cm) to the time it would take to walk across the U.S. The former feat of traveling to the moon was super-hard; the latter is comparatively impossible.

4.2.0.1Box 4.1: When Will We Get There?¶

It took 12 years for Voyager 2 to get to Neptune, which is “in our back yard.” The only spacecraft to date traveling fast enough to leave the solar system are the two Voyagers, the two Pioneers, and the New Horizons probe [23] . The farthest and fastest of this set is Voyager 1 at about 150 times the Earth–Sun distance after 43 years. The closest star is about 2,000 times farther. At its present speed of 17 km/s, it would reach the distance to the nearest star9 in another 75,000 years.

The fastest spacecraft on record as yet is the Parker Solar Probe, which got up to a screaming 68.6 km/s, but only because it was plunging (falling) around the sun. Because it was so close to the sun, even this amount of speed was not enough to allow it climb out of the sun’s gravitational grip and escape, as the five aforementioned probes managed to do. Even if Voyager 1 ended up with 70 km/s left over after breaking free of the solar system,10 it would still take 10: It only had 17 km/s left. 20,000 years to reach the distance to the nearest star. Note that human lifetimes are about 200 times shorter.

Pushing a human-habitable spacecraft up to high speed is immensely harder than accelerating these scrappy little probes, so the challenges are varied and extreme. For reference, the Apollo missions to the very nearby Moon carried almost 3,000 tons of fuel [24], or about [24]: (2020), Saturn V 80,000 times the typical car’s gasoline tank capacity. It would take

Table 4.2: Symbols, relative sizes, and distances in the solar system and to the nearest star. An AU is an Astronomical Unit, which is the average Earth–Sun distance of about 150 million kilometers. The fact that both the sun and moon are 240 of their radii away from Earth is why they appear to be a similar size on the sky, leading to “just so” eclipses.

7: For this, picture a grain of sand sitting on the bridge of your nose representing the earth, and a speck of dust in front of one

Glance over to where Mars would be if the earth is a grain of sand on your nose.

8: The last time we went this far was 1972.

[23]: (2020), List of artificial objects leaving the Solar System

9: It does not happen to be aimed toward the nearest star, however.

10: It only had 17 km / s left.

a typical car 2,000 years to spend this much fuel. Do you think the astronauts argued about who should pay for the gas? In fairness, fuel requirements don’t simply

Earth requires a hefty fuel load. Let’s relax the scale slightly, making the sun a chickpea (garbanzo bean). Earth is now the diameter of a human hair (easy to lose), and one meter from the sun. The moon is essentially invisible and a freckle’s-width away from the earth. The next star is now 300 km away (a 3-hour drive at freeway speed), while the Milky Way center is 1.5 million kilometers away. Oops. This is more than four times the actual Earth–Moon distance. We busted our scale again without even getting out of the galaxy.

So we reset and make the sun a grain of sand. Now the earth is 10 cm away and the next star is 30 km.11 Think about space this way: the 11: . . . a long day’s walk swarm of stars within a galaxy are like grains of sand tens of kilometers apart. On this scale, solar systems are bedroom-sized, composed of a brightly growing grain of sand in the middle and a few specks of dust (planets) sprinkled about the room.12 12: Even a solar system, which is a sort It gets even emptier in the vast tracts between the stars. The Milky Way extent on this scale is still much larger than the actual Earth, comparable to the size of the lunar orbit.

4.2.0.2Box 4.2: Cosmic Scales¶

It is not necessary to harp further on the vastness of space, but having come this far some students may be interested in completing the visualization journey.

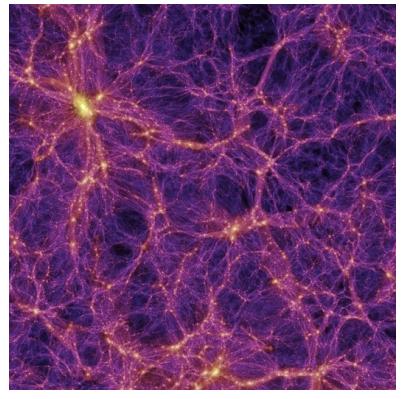

As mind-bogglingly large as the solar system is, not to mention that it itself is dwarfed by interstellar distances, which in turn are minuscule compared to the scale of the galaxy, how can we possibly appreciate the largest scales in the universe? Let’s start by making galaxies manageable. If galaxies are like coins (say a U.S. dime at approximately 1 cm diameter), they are typically separated by meterlike scales. The edge of the visible universe (see Sec. D.1; p. 392) would be only 1.5 km away. Finally, the picture is easy to visualize: coins as galaxies separated by something like arm’s length and extending over an area like the center of a moderately-sized town. We can even imagine the frothy, filamentary arrangement of these galaxies, containing house-sized (5–50 m) voids empty of coins (galaxies). See Figure 4.3 for a visual explanation.

But penetrating the nature of the individual galaxies (coins, in the previous example scale) is extremely daunting: they are mostly empty space, and by the time we reduce the galaxy to a manageable scale (say 10 km, so that we can picture the whole thing as city-sized), individual stars are a few tenths of a meter apart and only about 50 atoms across (roughly 10 nm). Cells and bacteria are about 100–1,000 times larger than this. So it’s nearly impossible to conceive of the scale of the galaxy while simultaneously appreciating the sizes of the stars and just how much space lies between.

scale with distance for space travel, unlike travel in a car. Still, just getting away from

11: ...a long day’s walk

of local oasis within the galaxy, is mostly empty space.

Figure 4.3: Galaxies are actually distributed in a frothy foam-like pattern crudely lining the edges of vast bubbles (voids; appearing as dark regions in the image). This structure forms as a natural consequence of gravity as galaxies pull on each other and coalesce into groups, leaving emptiness between. This graphic shows the bubble edges and filaments where galaxies collect. The larger galaxies are bright dots in this view—almost like cities along a 3-dimensional web of highways through the vast emptiness. From the Millennium Simulation [25].

Given the vastness of space, it is negligent to think of space travel as a “solution” to our present set of challenges on Earth—challenges that operate on a much shorter timescale than it would take to muster any meaningful space presence. Moreover, space travel is enormously expensive energetically and economically (see Table 4.3). As we find ourselves competing for dwindling one-time resources later this century, space travel will have a hard time getting priority, except in the context of escapist entertainment.13

4.2.1reality 4.2 The Wrong Narrative¶

Humans are not shy about congratulating themselves on accomplishments, and yes, we have done rather remarkable things. An attractive and common sentiment casts our narrative in evolutionary terms: fish crawled out of the ocean, birds took to the air, and humans are making the next logical step to space—continuing the legacy of escaping the bondage of water, land, and finally Earth. It is a compelling tale, and we have indeed learned to escape Earth’s gravitational pull and set foot on another body.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Just because we can point to a few special example accomplishments does not mean that such examples presage a new normal. A person can climb Mt. Everest, but it is not ever likely to become a commonplace activity. We can build a supersonic passenger airplane for trans-atlantic flight, but it does not mean it will be viable to sustain.14 14: . . . or even still available today (see the One can set up a backyard obstacle course for squirrels and generate viral videos, but the amusing demonstration does not signal a “new normal” in backyard design. We need to separate the possible from the practical. The moon landings might then be viewed as a nifty stunt—a demonstration of capability—rather than a path to our future. We encountered similar arguments in Chapter 2 in relation to decoupling: just because it can happen in certain domains of the economy does not mean that the entire economy can decouple and “defy gravity.”

The attractive evolutionary argument misses two critical facets of reality. When fish crawled out of the sea, they escaped predation (as the first animals on land) and found new food sources free of competition. That’s a win-win: less dangerous, more sustenance.15 15: Evolution works on exploiting advan-Likewise, when birds took flight (or we could discuss insects, which beat the birds to it), it was a similar story: evade ground-based predators who could not fly, and access a whole new menu of food—another win-win.

Going to space could easily be cast as a lose-lose. It’s an extremely hostile environment offering no protection or safe haven,16 and there’s nothing to eat.17 Think about it: where would you go to grab a bite in our solar system at present, outside of Earth? And a solar system is an absolute oasis compared to the vast interstellar void. The two factors that jointlyTable 4.3: Approximate/estimated costs, adjusted for inflation (M = million; B = billion). [26–29]

| Effort | Cost |

|---|---|

| Apollo Program | $288B |

| Space Shuttle Launch | $450M |

| Single Seat to ISS | $90M |

| Human Mars Mission | $500B |

13: . . . which is great stuff as long as it does not dangerously distort our perceptions of

story of the Concorde; Box 2.2; p. 22)

tages, favoring wins and letting the “lose” situations be out-competed.

16: Earth is the safe haven.

burgers have ever smacked into a space capsule.

promoted One “win” some imagine from space is evolution onto land and into the air will not operate to “evolve” us into space. It’s a much tougher prospect. Yes, it could be possible to grow food on a spacecraft or in a pressurized habitat, but then we are no longer following the evolutionary meme of stumbling onto a good deal.

4.2.1.1Box 4.3: Accomplishments in Space¶

Before turning attention to what we have not yet done in space, students may appreciate a recap of progress to date. The list is by no means exhaustive, but geared to set straight common misconceptions.

- I 1957: Sputnik (Soviet) is the first satellite to orbit Earth.

- I 1959: Luna 3 (Soviet; unmanned) reaches the moon in a fly-by.

- I 1961: Yuri Gagarin (Soviet), first in space, orbits Earth once.

- I 1965: Alexei Leonov (Soviet) performs the first “space walk.”

- I 1965: Mariner 4 (U.S.; unmanned) reaches Mars.

- I 1968: Apollo 8 (U.S.) puts humans in lunar orbit for the first time.

- I 1969: Apollo 11 (U.S.) puts the first humans onto the lunar surface.

- I Pause here to appreciate how fast all this happened. It is easy to see why people would assume that Mars would be colonized within 50 years. Attractive narratives are hard to retire, even when wrong.

- I 1972: Apollo 17 (U.S.) is the last human mission to the moon; only 12 people have walked on another solar system body, the last about 50 years ago.

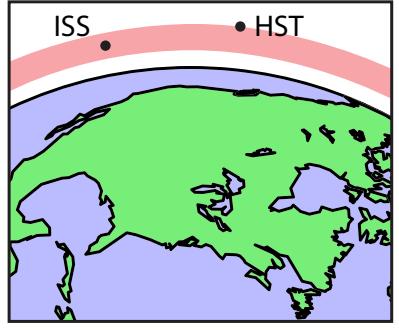

- I 1973–now: as of this writing (2020), humans have not ventured farther than about 600 km from Earth’s surface (called low earth orbit, or LEO; see Figure 4.4) since the end of the Apollo missions.

- I 1981–2011: U.S. operates the Space Shuttle, envisioned to make space travel routine. After 135 launches (two ending in catastrophe), the shuttle was retired, leaving the U.S. with no human space launch capacity.

- I 1998–now: The International Space Station (ISS) [30] provides an experimental platform and maintains a presence in space. It is only 400 km from Earth’s surface (4-hour driving distance), and—despite its misleading name—is not used as a space-port hub for space travel. It is the destination.

4.2.2access to materials. Yet Earth is already wellstocked with elements from the Periodic Table, and the economics of retrieval from space are prohibitive in any case.¶

Figure 4.4: The pink band indicates the farthest humans have been from the surface of the earth for the last ∼ 50 years. The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) orbits at the top of this band at 600 km altitude, and the International Space Station in the middle at 400 km. Beyond the thin black line outlining the globe, Earth’s atmosphere is too tenuous to support life.

[30]: (2020), International Space Station

4.2.34.3 A Host of Difficulties¶

If undeterred by the vast emptiness, hostile conditions, or lack of humansupporting resources in space, then maybe it’s because you believe

human ingenuity can overcome these challenges. And this is correct to a degree. We have walked on one other solar system body.18 We have had 18: The last Apollo landing was in 1972. individuals spend a year or so in earth orbit. Either these represent first baby steps to a space future, or just rare feats that we can pull off at great effort/expense. How can we tell the difference?

4.2.3.1Box 4.4: Comparison to Backpacking¶

The way most people experience backpacking is similar to how we go about space exploration: carry on your back all the food, clothing, shelter, and utility devices that will be needed for a finite trip duration. Only air and water are acquired in the wild. For space travel, even the air and water must be launched from Earth. So space travel is like a glorified and hyper-expensive form of backpacking—albeit offering breathtaking views!.

One way to probe the demonstration vs. way-of-the-future question is to list capabilities we have not yet demonstrated in space that would be important for a space livelihood, including:

- 1. Growing food used for sustenance;

- Surviving long periods outside of Earth’s magnetic protection from cosmic rays;19 19: The ISS (space station) remains within

- Earth’s protection. 3. Generating or collecting propulsive fuel away from Earth’s surface;

- Long-term health of muscles and bones for periods longer than a year in low gravity environments;

- Resource extraction for in-situ construction materials;

- Closed-system sustainable ecosystem maintenance;

- Anything close to terraforming (see below).

It would be easier to believe in the possibility of space colonization if we first saw examples of colonization of the ocean floor.20 Such an environ- 20: Even just 10 meters under the surface! ment carries many similar challenges: native environment unbreathable; large pressure differential; sealed-off self-sustaining environment. But an ocean This is not to advocate ocean floor habidwelling has several major advantages over space, in that food is scuttling/swimming just outside the habitat; safety/air is a short distance away (meters); ease of access (swim/scuba vs. rocket); and all the resources on Earth to facilitate the construction/operation (e.g., Home Depot not far away).

Building a habitat on the ocean floor would be vastly easier than trying to do so in space. It would be even easier on land, of course. But we have not yet successfully built and operated a closed ecosystem on land! A few artificial “biosphere” efforts have been attempted, but met with failure [31]. If it is not easy to succeed on the surface of the earth, how [31]: (2020), Biosphere 2 can we fantasize about getting it right in the remote hostility of space, lacking easy access to manufactured resources?

18: The last Apollo landing was in 1972.

19: The ISS (space station) remains within Earth’s protection.

20: Even just 10 meters under the surface!

tation as a good idea; it is merely used to illustrate that space habitation is an even less practical idea, by far.

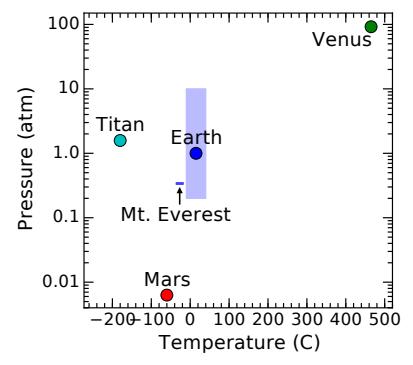

On the subject of terraforming, consider this perspective. Earth right now has a problem of excess CO2 as a result of fossil fuel combustion (the subject of Chapter 9). The problem has flummoxed our economic and political systems, so that not only do we seem to be powerless to revert to pre-industrial CO2 levels, but even arresting the annual increase in emissions appears to be beyond our means. Pre-industrial levels of CO2 measured 280 parts per million (ppm) of the atmosphere, which we will treat as the normal level. Today’s levels exceed 400 ppm, so that the modification is a little more than 100 ppm, or 0.01% of our atmosphere.21 Meanwhile, Mars’ atmosphere is 95% CO2. So we might say that Earth has a 100 ppm problem, but Mars has essentially a million part-per-million problem. On Earth, we are completely stymied by a 100 ppm CO2 increase while enjoying access to all the resources available to us on the planet. Look at all the infrastructure available on this developed world and still we have not been able to reverse or even stop the CO2 increase. How could we possibly see transformation of Mars’ atmosphere into habitable form as realistic, when Mars has zero infrastructure to support such an undertaking? We must be careful about proclaiming notions to be impossible, but we can be justified in labeling them as outrageously impractical, to the point of becoming a distraction to discuss. Figure 4.5 further illustrates the giant gap between tolerable conditions and actual atmospheres on offer in the solar system.

Terraforming is the speculative idea of trans-forming a planet so its atmosphere resembles that of Earth (chemical makeup, temperature, pressure) and can support human life.

21: While the increase from 280 to 400 is about 50%, as a fraction of Earth’s total atmosphere, the ~ 100 ppm change is 100 divided by one million (from definition of ppm), or 0.01%.We also should recall the lesson from Chapter 1 about exponential growth, and how the addition of another habitat had essentially no effect on the overall outcome, aside from delaying by one short doubling time. Therefore, even if it is somehow misguided to discount colonization of another solar system body, who cares? We still do not avoid the primary challenge facing humanity as growth slams into limitations in a finite world (or even finite solar system, if it comes to that).

4.2.44.4 Exploration’s Role¶

It is easy to understand why people might latch onto the idea that we will likely leverage our exploration of space into ultimate colonization. Much as early explorers of our planet opened pathways for colonization of “new worlds,” the parallels in exploring literal new worlds like planets are obvious.22 In short, it is a familiar story, and therefore an easy “sell” to primed, undoubting minds. Plus, we’re captivated by the novelty and challenge space colonization represents—as attested by a vibrant entertainment industry devoted to stories of eventual life in space. But not all exploration leads to settlement, and entertainment is not truth.Humans have explored (a small portion of) the crushing deep ocean, scaled Earth’s highest and wholly inhospitable peaks, and visited the harsh ice cap at the north pole. In such instances, we had zero intention of establishing permanent residence in those locations. They represented

forming a planet so its atmosphere resembles that of Earth (chemical makeup, temperature, pressure) and can support human life.

about 50%, as a fraction of Earth’s total atmosphere, the ∼ 100 ppm change is 100 divided by one million (from definition of ppm), or 0.01%.

Figure 4.5: Rocky-body atmospheres in the solar system, showing average temperature (Celsius) and pressure (atmospheres). The range of “comfort” for Earth is shown as a blue rectangle going from −10◦C to 40◦C and 0.2 atm (where the atmosphere would need to be 100% oxygen) to (arbitrarily) 10 atm. Not only are the other bodies far outside our comfort range, the compositions are noxious, and lack oxygen. Bear in mind that a change of even a few degrees as in climate change—is a big deal. Even Mt. Everest, where humans can survive for only a few hours with supplemental oxygen is substantially more hospitable than Mars.

across a span of (life-supporting) ocean about twice the size of Europe. Reaching Mars involves a leap across inhospitable space 5,000 times the diameter of Earth not very similar at all.

places to test our toughness and also learn about new environments. We do not view these sorts of explorations as mistakes just because they did not pave the way for inhabitation. Rather, we speak fondly of such excursions as feathers in our collective cap: feats that make us proud as a species. Space might be viewed in a similar way: superlative in terms of challenge and wonderment, reflecting positively on our curiosity, drive, ingenuity, and teamwork. We also derive benefits23 in the way of technological advancement propelled by our quest to explore, and in furthering our scientific understanding of nature. 23: ... among them a deeper appreciation for the rare and precious Earth

So even if space does not fulfill the fantasy of continued human expansion across the cosmos, it is in our nature to at least explore it. We would do well to put space exploration in the category of conquering Mt. Everest rather than that of Europeans stumbling upon the West Indies (one is as imminently uninhabitable as the other is inhabitable). Let us not make the mistake of applying the wrong narrative to space.

Many positive things might be said about space exploration, and hopefully we continue poking into our outer environment indefinitely. Yet hoping that such exploration is a pathway to human colonization of space is probably wrong and almost certainly counterproductive at present, given the short timescale on which human expansion is likely to collide with Earth’s limits. Despite the pessimistic tone of this chapter, the author is himself captivated by space, and has built a life around it: Star Wars was a transformative influence as a kid, and later Star Trek. The movie The Right Stuff is still a favorite. He has peered to the edge of the universe—first through a 10-inch tele-

If, in the fullness of time, we do see a path toward practical space colonization, then fine. But given the extreme challenge and cost both energetically and economically, and for what could only be a tiny footprint in the near term—it seems vastly more prudent to take care of our relationship with Planet Earth first, and then think about space colonization in due time, if it ever makes sense. Otherwise, not only do we spend precious resources unwisely, but (even worse) our mindset is tainted by unrealistic dreams that diminish the importance of confronting the real challenge right here on the ground. We need to have our heads in the real game. Perhaps twenty øne piløts said it best in the song Stressed Out:

We used to play pretend, give each other different names We would build a rocket ship and then we’d fly it far away Used to dream of outer space but now they’re laughing at our face Saying, “Wake up, you need to make money.” Yeah.

Space colonization might be treated as a pretend fantasy for the moment. We would be better off waking up to face real here-and-now challenges. In some sense, perhaps the only way to achieve the dream of migration to space—should that be in the cards at all—is to first pretend that it is impossible and turn attention to the pressing matters on Earth. Otherwise we risk failing at both efforts.

for the rare and precious Earth

the author is himself captivated by space, and has built a life around it: Star Wars was a transformative influence as a kid, and later Star Trek. The movie The Right Stuff is still a favorite. He has peered to the edge of the universe—first through a 10-inch telescope he built in high school, and later using the largest telescopes in the world. He has worked on a Space Shuttle experiment, met astronauts, knew Sally Ride, and spent much of his career building and operating a laser system to bounce and detect individual photons off the reflectors placed on the lunar surface by the Apollo astronauts (as a test of the fundamental nature of gravity), which directly inspired part of a Big Bang Theory episode via personal interactions with the show’s writers. So a deep fondness for space? Yes. Would volunteer to go to the moon or Mars? Yes. Believes it holds the key to humanity’s future? No.

4.2.4.1Box 4.5: Q&A on State of Exploration¶

After reading the first draft of this chapter, students had a number of remaining questions. Here are some of them, along with the author’s responses.

- How long before we live on other planets?

Maybe never.24 The staggering distances involved mean that our own solar system is effectively the only option. Within the solar system, Mars is the most hospitable body—meaning we might live as long as two minutes without life support. By comparison, Antarctica and the ocean floor are millions of times more practical, yet we do not see permanent settlements there.25 24: True, never is a long time. The notion that we may never colonize space may seem preposterous to you now. Check back at the end of the book. The odds favor a more boring slog, grappling with our place in nature. 25: Staffed research stations are not the2. What is the status of searches for other planets to colonize? Antarctica.

We understand our solar system pretty well. No second homes stand out. We have detected evidence for thousands of planets around other stars [32], but do not yet have the sensitivity to detect the presence of earth-like rocks around most stars. It is conceivable that we will have identified Earth analogs in the coming decades, but they will give new meaning to the words “utterly” and “inaccessible.” [32]: IPAC/NASA (2020), NASA Exoplanet Archive3. Haven’t we benefited from space exploration in the technology spin-offs, like wireless headsets and artificial limbs?

No doubt! The benefits have been numerous, and I would never characterize our space efforts to date as wasted effort. It’s just that what we have done so far in space does not mean that colonization is in any way an obvious or practical next step. Actually, the banner image for this chapter from the Apollo 8 mission captivated the world and made our fragile shell of life seem all the more precious. So perhaps the biggest benefit to our space exploration will turn out to be a profound appreciation for and attachment to Earth!

4.2.54.5 Upshot: Putting Earth First¶

The author might even go so far as to label a focus on space colonization in the face of more pressing challenges as disgracefully irresponsible. Diverting attention in this probably-futile26 effort could lead to greater 26: . . . at least on relevant time scales total suffering if it means not only mis-allocation of resources but perhaps

that we may never colonize space may seem preposterous to you now. Check back at the end of the book. The odds favor a more boring slog, grappling with our place in nature.

same as human settlements, in the case of

Archive

26: . . .at least on relevant time scales

more importantly lulling people into a sense that space represents a viable escape hatch. Let’s not get distracted!

The fact that we do not have a collective global agreement on priorities or the role that space will (or will not) play in our future only highlights the fact that humanity is not operating from a master plan27 that has been well thought out. We’re simply “winging it,” and as a result potentially wasting our efforts on dead-end ambitions. Just because some people are enthusiastic about a space future does not mean that it can or will happen.

27: Prospects for a plan are discussed in Chapter 19.It is true that we cannot know for sure what the future holds, but perhaps that is all the more reason to play it safe and not foolishly pursue a high-risk fantasy.28 From this point on, the book will turn to issues more tangibly relevant to life and success on Planet Earth.

28: Tempted as we may be by the e-mail offer from the displaced Nigerian prince to#### Box 4.6: Survey Says?

It would be fascinating to do a survey to find out how many people think that we will have substantial populations living off Earth 500 years from now. It is the author’s sense that a majority of Americans believe this to be likely. Yet, if such a future is not to be—for a host of practical reasons, including the possibility that we falter badly and are no longer in a position to pursue space flight—we would find ourselves in a situation where most people may be completely wrong about the imagined future. That would be a remarkable state of affairs in which to find ourselves—though not entirely surprising.

4.2.64.6 Problems¶

- 1. If the sun were the size of a basketball, how large would Earth be, and how far away? How large would the moon be, and how far from Earth, at this scale?

- Find an Earth globe and an object about one-fourth its size to represent the moon, then place at the appropriate distance apart. Report on how far this is. Take a personalized/unique picture to document, and take some time appreciating how big Earth would look from the moon.

offer from the displaced Nigerian prince to help move his millions of dollars to a safe account, most of us know better than to bite. The promise of wealth can lead the gullible to ruin.

i This kind of exercise might seem like a hassle, but it can really help internalize the scales in a way words never will.

i By doing this, you can get maybe 2% of the enjoyment of a trip to the moon for less than one-billionth the cost: a real bargain! Can you make out Florida? Japan?

- 5. Highway 6563 in New Mexico has signs along a roughly 30 km stretch of road corresponding to the solar system scale from the Sun to Neptune. On this scale, how large would Earth, Sun, and Jupiter be, in diameter? Express in convenient units appropriate to the scale.

- Use Table 4.1to accumulate (multiplicatively combine) scale factors and ask: which is a bigger ratio: the distance to the nearest star compared to the diameter of Earth, or the distance to the edge of the universe compared to that to the nearest star? Compared to the large numbers we are dealing with, is one much smaller or much bigger than the other, or are they roughly the same?

- 9. It may be tempting to compare Earth to a life-sustaining oasis in the desert—maybe spanning 100 m. But this is a pretty misleading view. One way to demonstrate this is to consider that in a real desert, the next oasis might be a perilous 100 km journey away. Using the ratio of distance to size (diameter of planet or oasis), how close would another Earth have to be (and compare your answer to other solar system scales) to hold the analogy?29 29: In other words, oasis size is to distance How long would it take to drive this distance? Do we have another oasis or potential oasis within this distance?

- Another way to cast Problem 9 is to imagine that the actual distance between Earth and a comparable oasis is more like the distance between stars.30 In this case, how far would the next oasis be in the desert if we again compare the 100 m scale of the oasis to the diameter of the Earth?31 How long would it take to drive between oases at freeway speeds (cast in the most informative/intuitive units)?

- On the eighth bullet of Box 4.3 (the one that asks you to pause), imagine someone from the year 2020 traveling back 50 years and explaining that we have not been to the moon since 1972, and that Americans get to space on Russian rockets. How believable do you think they would be, and what assumptions might be made to reconcile the shock?

- Prior to exposure to this material, what would you honestly have said in response to: How far have humans been from the planet in

i This is why eclipses are special on Earth.

between oases as Earth’s diameter is to how far?

30: . . . since Earth is the only livable “oasis” in our own solar system

31: In other words, Earth diameter is to interstellar distances as a 100 m oasis is to how far?

i The insight you develop will not depend on exact choices for distance and speed, as long as they are reasonable.

the last 45 years;

- a) 600 km (about 1 10 Earth radius; low earth orbit)

- b) 6,000 km (roughly Earth radius)

- c) 36,000 km (about 6 푅⊕; around geosynchronous orbit)

- d) 385,000 km (approximate distance to the moon)

- e) beyond the distance to the moon

Explain what led you to think so (whether correct or not).

- List at least three space achievements that impress you personally, even if they do not bear directly on colonization aims.

- In the enumerated list beginning on page 60, which item is most surprising to you as not-yet accomplished, and why?

- List three substantive challenges that prevented successful longterm operation of the artificial biosphere project [31] .

- Since Figure 4.5 spans the range of atmospheres found in our solar system, we can imagine how likely it would be that a random planet might happen to be livable for humans.32 32: . . . just in terms of temperature and Imagine throwing a dart at the diagram to get a random instance. How likely are we to hit the comfort zone of Earth, by your estimation?

- Come up with three examples (not repeating items in the text) of feats that are technically possible, but not common or practical.

- 18. For some perspective, imagine you were able to drive your car up a ramp to an altitude characteristic of low-earth orbit (about 320 km, or 200 miles). It takes about 5 × 1010 J of energy33 33: We’ll encounter gravitational potential to win the fight against gravity. Meanwhile, each gallon of gasoline can do about 25 × 106 J of useful work. How many gallons would it take to climb to orbital height in a car? Roughly how many miles per gallon is this (just counting vertical miles)?

- In Problem 18, we ignored the energy required to provide the substantial orbital speed (∼ 8 km/s, but will not need), which essentially doubles the total energy.34 How much gasoline will it now take, and how massive is the fuel if gasoline is 3 kg per gallon, compared to the 1,500 kg mass of the car?

[31]: (2020), Biosphere 2

pressure; ignoring composition and a host of other considerations!

energy later, but this quantity is computed as 푚 푔 ℎ with 푚 ≈1,500 kg.

34: The same amount of energy to climb against gravity must go into accelerating to speed (kinetic energy).

i Given this mass of fuel, and its significance compared to the car’s mass, we can see that we’ve underestimated the fuel required since we’ll have to put substantial additional energy into lifting the fuel away from the earth.