15.1Nuclear Energy¶

Most of the energy forms discussed thus far derive from sunlight either contemporary input or fossilized storage. The fuel for nuclear energy is truly ancient, predating the solar system. The heavy elements participating in fission were produced by astrophysical cataclysms (most likely merging neutron stars), while the hydrogen building blocks for fusion originated in the Big Bang itself. In brief, fission involves the splitting of heavy nuclei into smaller pieces, while fusion builds larger nuclei from smaller ones.

While only fission has been successfully implemented as a source of societal energy, both types essentially boil down to the same thing: a source of heat to make steam and drive a heat engine. How and why nuclear material generates heat will be a primary focus of this chapter. Many practical concerns surround nuclear power, such as safety, weapons, waste, and proliferation of dangerous material. Self-pride for the impressive accomplishment of mastering nature well enough to implement nuclear power may not adequately justify continued reliance upon it—even if it is not a direct emitter of CO2.

Understanding nuclear energy requires a longer journey than was needed for hydroelectricity, wind, and solar photovoltaics. We first learn about the nucleus and its many configurations, how nuclei transform from one to another through radioactive decay, the role plays, and finally dig into the workings of fission and fusion.# 15.1 The Nucleus

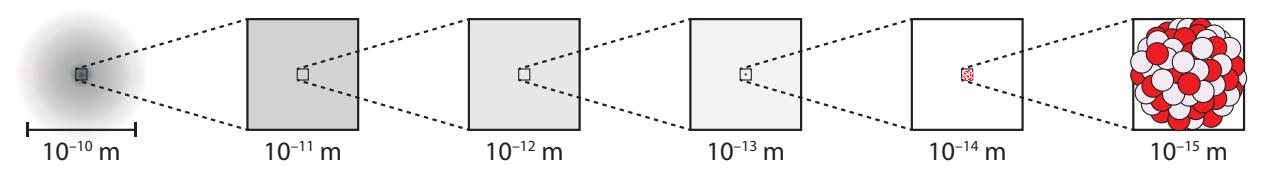

First, what is a nucleus? Every (neutral) atom consists of a positivelycharged nucleus surrounded by a cloud of negative electrons (Figure 15.1).

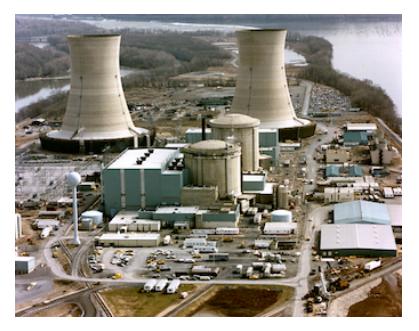

Cooling towers of the decommissioned Satsop nuclear power plant in Washington. Photo credit: Tom Murphy

- © 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

escholarship .org /uc /energy\ _ambitions. - ... which defines the size of the atom

The nucleus is about 100,000 times smaller than the electron cloud,1 but 1: . . . which defines the size of the atom contains 99.97% of the atom’s mass in a super-dense nugget composed of protons (positive charge) and neutrons (no charge). While electromagnetic forces vehemently resist the close congregation of positivelycharged protons, the strong nuclear force overpowers this objection and sticks the protons and neutrons together in a stable existence.

Figure 15.1: Zooming in on an atom in steps of 10×. At left, we see the entire extent of the atom’s electron cloud. For a while, no nucleus is visible, being 100,000 times smaller than the atom itself. The nucleus within an atom is like a small dust grain in a bedroom.

By convention, the number of protons is labeled as and the number of neutrons as . The total number of nucleons2 is called the mass number: . It’s just counting.Picking carbon as an example, all carbon atoms have : six protons.3 Most carbon atoms (98.93%) have , making . But some isotopes carry a different number of neutrons. In natural carbon samples, 1.07% have , making . We label such an isotope as 13C ( ), or sometimes 6 13 C ( ), or even in some cases the fully-described 6 13 C7 ( ). The latter two forms are somewhat redundant—though sometimes appreciated/helpful—because all carbon atoms have , and always. Therefore, 13C says it all, provided you can easily find or remember the number for carbon.4 The general pattern for an isotope of element X is ZAXN. Other common designations are, for example, C12, C13, U238, or C-12, C-13, U-238 as alternatives to 12C, 13C, and 238U, respectively.Example 15.1.1 Write down all the various ways of designating the isotope of plutonium (Pu; 94 protons) that has mass number 퐴 = 239.

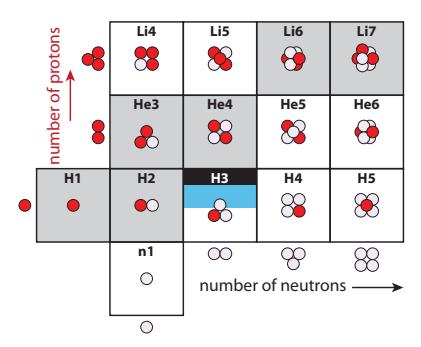

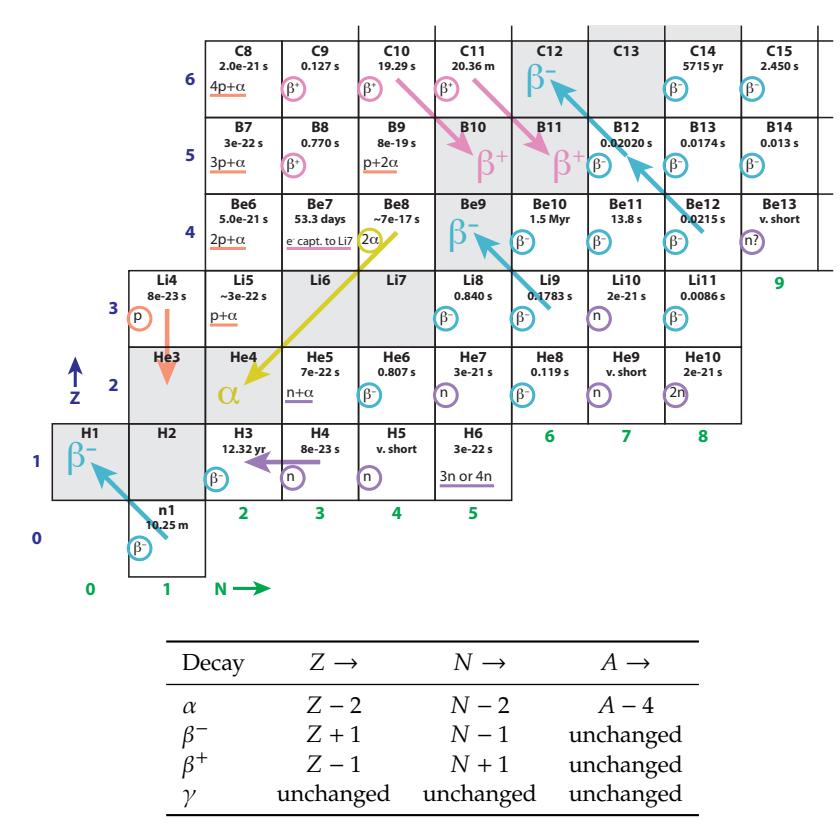

First, the math. and so . Starting at the simple end and working up, we can label this Pu239, Pu-239, 239Pu, 94239Pu, and finally 94239Pu145.The physicist’s version of the periodic table is called the Chart of the Nuclides, and contains a wealth of information. The basic layout idea is introduced in Figure 15.2, for the extreme low-mass end of nuclides.

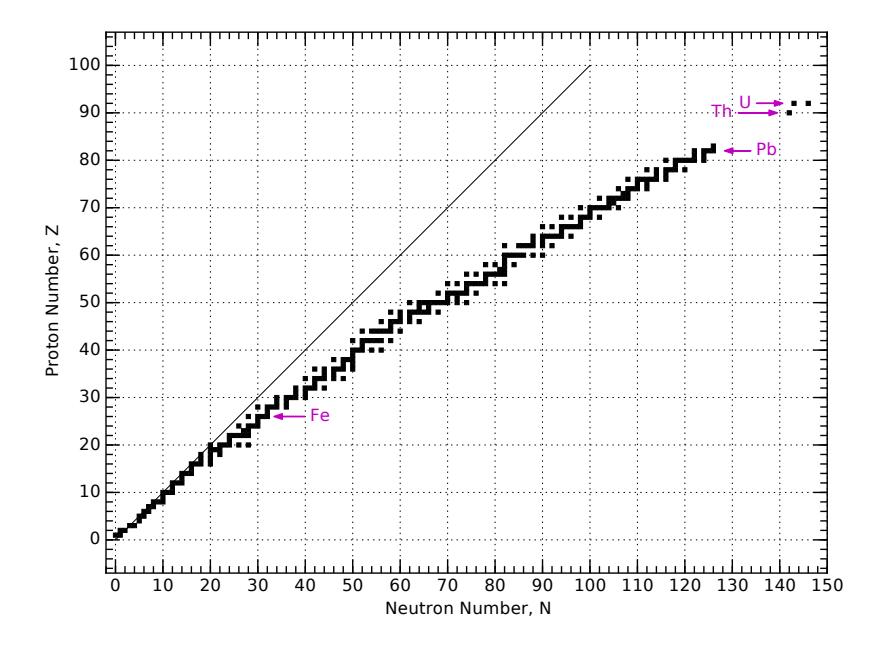

Definition 15.1.1 A nuclide is any unique combination of nucleons, so that every nucleus is one of the possible nuclides. For example, the nucleus is one nuclide, while is a distinct, different nuclide.Figure 15.3 provides a full view of the chart layout: neutron number, 푁, runs horizontally and proton number, 푍, runs vertically. Stable nuclei are indicated by black boxes at some particular integer value of 푁 and

© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

2: . . . a name describing either protons or neutrons: any nuclear constituent

3: One might say this is what defines the

4: ... just the sequential number labeling boxes in the periodic table: Fig. B.1 (p. 375)

Figure 15.2: Lower left start of the Chart of the Nuclides, shown pictorially in terms of the number of protons (red) and number of neutrons (lavender) in each nuclide. Gray boxes are stable nuclides, and H3 (tritium) is semi-stable for a decade or so.

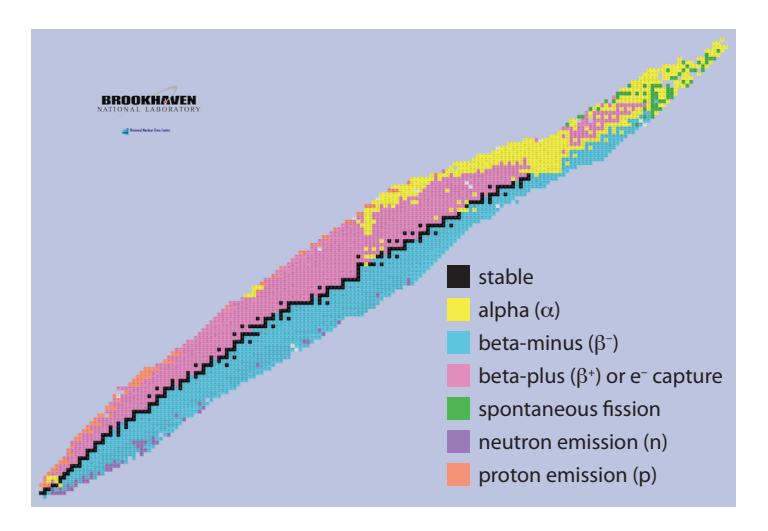

푍. Notice how they bend away from the 푁 = 푍 line, preferring to be neutron-rich. This can be traced to the fact that protons repel each other due to their electric charge, so the nucleus can be more tightly bound if fewer protons than neutrons are present—balanced against another penalty for being too far away from 푁 = 푍.

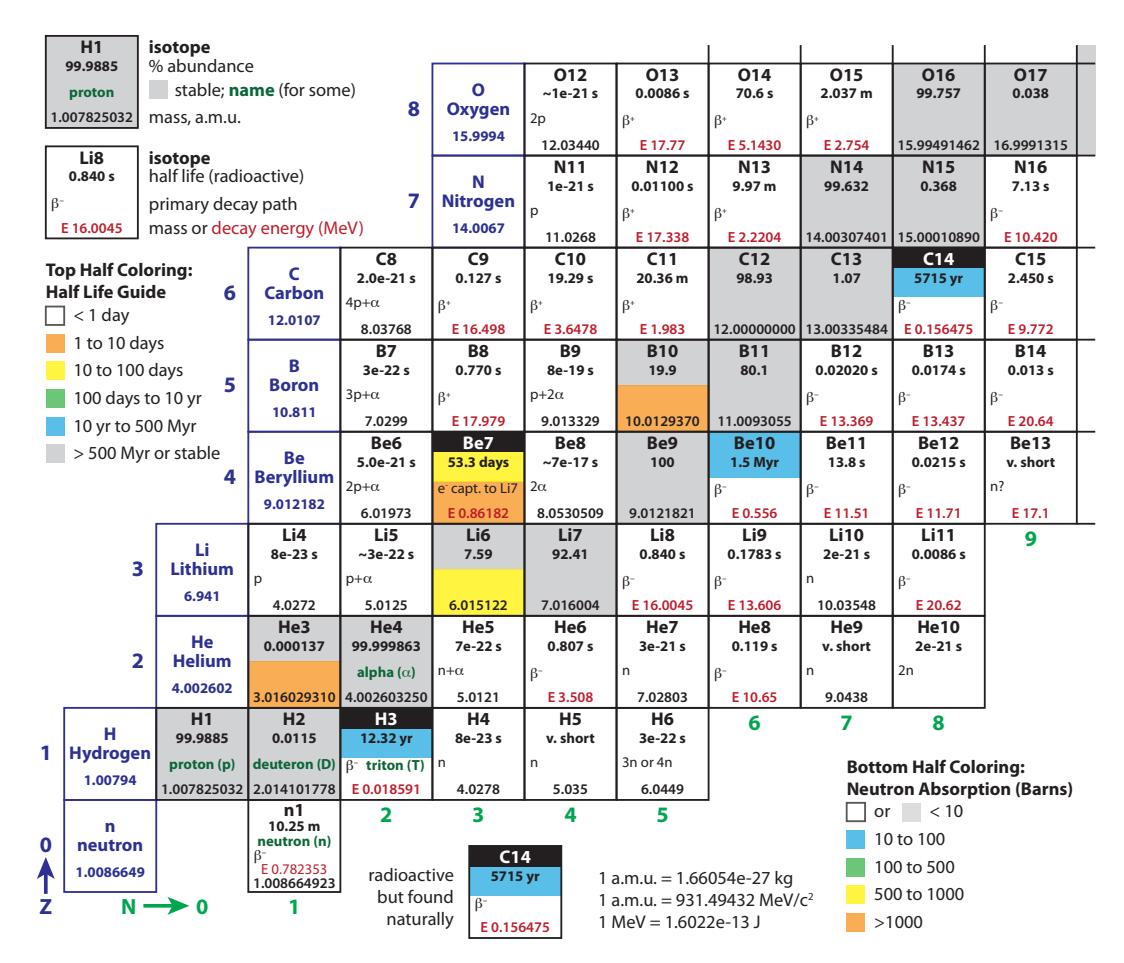

Figure 15.4 shows the lower-left corner of the chart in much greater detail.5 For each element (horizontal row), properties of all known isotopes are listed—even those that are radioactive and do not persist for even a small fraction of a second before decaying. Stable isotopes are denoted by gray boxes. The mass of each, in atomic mass units (a.m.u.)—defined so that the neutral 12C atom is exactly 12.0000 a.m.u.—is given, and the natural abundance as found on Earth, in percent. The Chart of the Nuclides lets us peak inside the periodic table in great detail, as Example 15.1.2 suggests.Example 15.1.2 From the Boron row (Z = 5) in Figure 15.4, we can see that 19.9% of boron is found in the form of 10B, while the other 80.1% is 11B.The weighted composite mass is therefore 0.199×10.0129370+0.801× 11.0093055, yielding 10.81103 a.m.u., which is the number presented as the molar mass on the periodic table.6 6: . . . and in the summary information in

Because the Chart of the Nuclides has neutron number, , increasing from left to right, and proton number, , increasing vertically, nuclei having the same mass number, , are arranged on diagonals. Notice that in the region shown in Figure 15.4, we never find more than one stable element at each mass number (constant ).Figure 15.3: Layout of the Chart of the Nuclides, showing positions of naturallyoccurring nuclei (stable or long-lived enough to be present on Earth). Stable nuclei tend to have more neutrons than protons—especially for heavier nuclei. This is why the track of stable nuclei bends away from the 푁 = 푍 diagonal line. Arrows point to important elements of iron, lead, thorium, and uranium at 푍 values of 26, 82, 90, and 92, respectively.

5: Even this level of detail is short of what can be found in the actual Chart of the Nuclides, which also provides quantitative values for neutron absorption, nuclear spins, excited states, additional decay paths and associated energies.

the blue box at the left of each row

Follow 퐴 = 12, for instance, from O12 through Be12, crossing through C12 as the only stable element of this mass.

Figure 15.4: Chart of the Nuclides for the low-mass end. Neutron number, 푁, increases toward the right (green numbering at bottom) and proton number, 푍, increases vertically (blue numbering at left). Scientific notation is expressed as, e.g., 8e–23, meaning 8 × 10−23. A wealth of information is included: spend some time studying the surrounding guides to learn what data each box contains.

15.215.2 Radioactive Decay¶

When one nuclide, or isotope changes into another, it does so by the process ofradioactive decay. Stable nuclides have no incentive to undergo such decays, but unstable nuclides will seek a more stable configuration through the decay process.

The black squares in Figure 15.3, or gray squares in Figure 15.4 are stable, 7 nature leaving all others as unstable, 8 meaning that they will undergo radioactive decay to a different nucleus after some time interval that is characterized by the nuclide’s half life.

Definition 15.2.1 The half life of a nuclide is the time at which the probability of decay reaches 50%. A large sample of such nuclides will be reduced to half the original number after one half-life. Each subsequent half-life interval removes another half of what remains.

7: . . . or long-lived enough to be found in

8: Nuclides are unstable if a lower energy (more stable) configuration is within easy reach, better balancing desire for against the cost of proton repulsion.Figure 15.4 lists a half-life9 for each unstable nuclide. For example, the half-life for a neutron (n1 in Figure 15.4) is 10.25 minutes, meaning that a lone neutron has a 50% chance of surviving this long. The process is statistical, so an individual neutron might only last 3 seconds, or might still be around in 15 or even 60 minutes. The predictive power is sharpened the larger the sample is: half will remain after 10.25 minutes.Example 15.2.1 If starting with 16 million separate neutrons, we would expect 8 million to still be present after 10.25 minutes, 4 million after 20.5 minutes, 2 million after 30.75 minutes, and down to 1 million neutrons in 41 minutes.

Correspondingly, a single isolated neutron has a 50% chance of still being around in 10.25 minutes, a 25% chance of lasting 20.5 minutes, and a 6.25% chance of surviving 41 minutes. Every half-life interval cuts the probability of survival in half again.

Table 15.1 summarizes these results, adding jumps to 10 and 24 half lives for illustration, ending at one neutron.

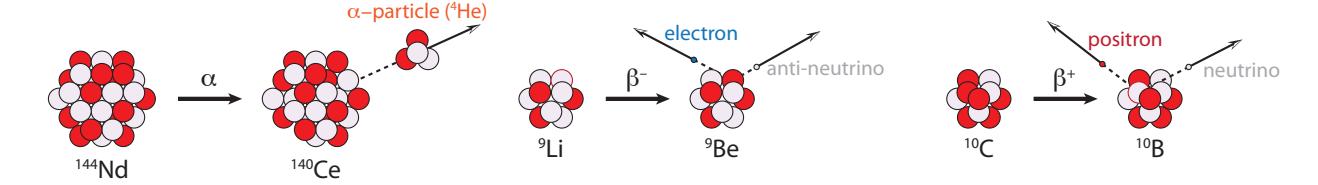

Luckily,radioactive decays don’t go just any which way, but stick to a very small menu of possible routes.When a decay happens, the nucleus always spits something out, which could be an electron, a positron, a helium nucleus (called an alpha particle), a photon, or more rarely might spit out one or more individual protons or neutrons. Because these particles can emerge at high speed (high energy), they are like little bullets firing at random times and directions into their surroundings. These bullets are potentially damaging to materials and biological tissues—especially DNA, able to cause mutations and/or initiate cancerous growth. The primary decay mechanisms pertaining to the vast majority of decays are listed below and accompanied by Figure 15.5.

9: . . . in units of seconds, minutes, hours, days, or years

Table 15.1: Decay of 16 million (M) neutrons, having a half life of 10.25 minutes, mirroring Example 15.2.1. Time is in minutes. The number remaining at each step is given, as well as the probability of any particular neutron surviving this long. After about four hours, only one would be expected to remain (and not for much longer).

| Time (min) | Half Lives | Remain | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 16 M | 100% |

| 10.25 | 1 | 8 M | 50% |

| 20.5 | 2 | 4 M | 25% |

| 30.75 | 3 | 2 M | 12.5% |

| 41.0 | 4 | 1 M | 6.25% |

| 102.5 | 10 | 15,625 | 0.1% |

| 246 | 24 | ~1 | 1/16M |

Figure 15.5: Radioactive decay mechanisms for , −, and +. Protons are colored red, and neutrons light purple. The total nucleon counts are correct for the two beta decays, but only schematic for the larger 144Nd nucleus used to illustrate alpha decay, which is predominantly seen only in heavier nuclei (aside from 5Li and 8Be). The positron is an anti-electron: a positively-charged antimatter counterpart to the electron. Neutrinos are sometimes called “ghost” particles for their near-complete non-interactivity with ordinary matter.1. Alpha decay (훼), in which a foursome of two protons and two neutrons—essentially a He 4 nucleus—leaps out.10 10: Helium is found mixed in with natural When this happens, the nucleus reduces its 푁 by two, reduces its 푍 by two, and therefore 퐴 by 4. On the chart of the nuclides, it moves two squares left and two squares down (see Figure 15.7). For example, Be 8 decays this way, essentially splitting into two He 4 nuclei;

gas, and derives from alpha particle decay of elements in the earth’s interior.

- Beta-minus (훽 −) decay is a manifestation of the weak nuclear force, in which a neutron within the nucleus converts to a proton, and in the process spits out an electron (훽 − particle, really just 푒 −) to conserve total electric charge, and a neutrino—which we will ignore.11 11: Perhaps it is fair to ignore neutrinos The mass number, 퐴 is unchanged, but 푁 goes down one and 푍 goes up one (gaining a proton and losing a neutron). Thus on the chart of nuclides the motion is one left, one up. It’s like a chess move (Figure 15.7);

- Beta-plus (훽 +) decay, like 훽 −, is a manifestation of the weak nuclear force, in which a proton within the nucleus converts to a neutron, emitting a positron (훽 +, or 푒 +, or anti-electron; a form of antimatter) again maintaining charge conservation, and an ignored neutrino. Similar to 훽 − decay, 퐴 is unchanged, but 푍 is reduced by one and 푁 gains one. On the chart, the move is diagonal: down one and right one (Figure 15.7).

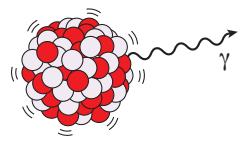

- Gamma decay (훾) happens when a nucleus is in an excited energy state, having been rattled by some other decay or bombardment, and it emits a high-energy photon, called a gamma ray, as it settles into a lower energy state (Figure 15.6). For 훾 decays, 푍, 푁, and 퐴 do not change, so the nucleus does not morph into another flavor, and thus does not move on the Chart of the Nuclides.

Figure 15.7 demonstrates the motion of each of these decays on the Chart of the Nuclides, and Table 15.2 summarizes the nucleon arithmetic.

since they ignore us. Neutrinos interact so infrequently with matter that a neutrino could fly through light years of rocky (Earth-like) material before being expected to hit something (interact). This extreme non-interactivity earns it the title of “ghost” particle.

Figure 15.6: Gamma decay of an excited nucleus.

Figure 15.7: Radioactive decays shown as moves on the “chess board” of the Chart of the Nuclides. The different decay types are color-coded to match Figure 15.8, and are only shown in a few representative squares. Decays frequently occur in a series, one after the other (a decay chain), as hinted by the double-sequence starting at Be12 and ending on C12. Note that the square of every unstable nuclide indicates a decay type, even if arrows are not present.Table 15.2: Summary of decay math on nucleon counts.

© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

15.2.0.0.1Example 15.2.2 What will the fate of He 8 be, according to Figure 15.4?¶

We can play this chess game! According to the chart, the primary decay mechanism of He8 is with a half-life of about a tenth of a second. It will become 8Li, which hangs around for about a second before undergoing another decay to 8Be. This one lasts almost no time at all ( s) before decay into two alpha particles (two 4He). Such a sequence is called a decay chain.As is evident in Figure 15.8, unstable isotopes above the stable track in Figure 15.3 tend to undergo 훽 + decays to drive toward stable nuclei, while those below the track tend to experience 훽 − decays to drive up toward the stable track. The 훼 decays are more common for heavy nuclei (around uranium), which drive toward the end of the train of stable elements in Figure 15.3, ending up around lead (Pb). We can understand the abundance of lead as a byproduct of heavy-element decay chains.

Figure 15.8: Another view of the Chart of the Nuclides, color coded to indicate prevailing decay modes as a function of position on the chart. Note that 훽 + sometimes captures an electron rather than emitting a positron, but amounting to the same thing, essentially. From U.S. DoE.

15.2.0.0.2Box 15.1: The Weak Nuclear Force¶

An aside worth making is that having discussed beta decays, governed by the weak nuclear force, we have now covered all four known forces of nature: gravity, electromagnetism, the weak nuclear force, and the strong nuclear force. That’s it: a small menu, really. The latter three are unified into a Standard Model of Physics, but gravity—described by General Relativity—has defied all attempts at “grand unification,” or a “theory of everything” trying to unite all four forces under a single theoretical framework. One implication is that known physics offers no other “magic” solutions to our energy needs. No new forces have come to light in more than half-a-century, despite dramatic advances in tools to probe the fundamental nature of physics.

15.315.3 Mass Energy¶

Energy—whatever the form—has mass and actually changes the weight of something, although almost imperceptibly. A hot burrito has more mass than the exact same burrito—atom for atom—when it’s cold.12 Most of us are familiar, at least casually, with the famous relation . 12: The burrito is also ever-so-slightly more Most of us are familiar, at least casually, with the famous relation . More helpfully, we might express it as

(15.1)

where the Δ symbols indicate a change in energy or mass, and m/s is the speed of light. Using kilograms for mass results in Joules for energy. Because is such a large number (nearly 1017), the mass change associated with daily/familiar energy quantities is negligibly small. Box 15.2 explains why is valid for all energy exchanges—not just nuclear ones—but generally results in mass changes too small to measure in non-nuclear contexts. Earlier, we discussed conservation of energy. More correctly, we observe conservation of massenergy. That is to say, a system can actually gain or lose net energy if the mass changes correspondingly. In the case of nuclear energy release, the “new” energy comes at the expense of reduced mass.# Box 15.2: 퐸 = 푚푐2 Everywhere

Physics is not selective about when we might apply . It always applies, to every situation. It’s just that outside of nuclear reactions it does not result in significant mass differences.For example, after we eat a 1,000 kcal burrito to fuel our metabolism, we expend the energy13 and lose mass according to . Since MJ (1,000 kcal), we find the associated mass change is kg, which is ten orders-of-magnitude smaller than the mass of the burrito itself.14 So we’d never notice, even though it’s really there.

13: ... ultimately given off as thermal energy to our environment

14: This amount of mass corresponds toWhen we wind up a mechanized toy, coiling a spring, we put energy into the spring and the toy actually gets more massive! But for every Joule we put in, the mass only increases by about 10−17 kg. Forgive us for not noticing. Only in nuclear contexts are the energies large enough to produce a measurable difference in mass.

Example 15.3.1 Since mass and energy are intimately related, it is common to express masses in energy terms. How would we express 12.0 a.m.u. in MeV (a unit of energy; see Sec. 5.9; p. 78)?

1 a.m.u. is equivalent to 1.66 × 10-27 kg (last row of Table 15.4), so 12 a.m.u. is 1.99×10-26 kg. To get to energy, apply , computing to 1.8 × 10-9 J of energy. Since 1 MeV is 1.6 × 10-13 J, we end up with*reative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.;

massive if it has kinetic energy, gravitational potential energy, or any form of energy. A battery is more massive when charged, even if no atoms or electrons are added. Incidentally, charging a battery does not mean literally adding electrical charges (adding particles), but amounts to rearranging electrons among the atoms within the battery.

ergy to our environment

that of a tiny length of hair that is shorter than it is wide.

© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

15.3.0.0.111,200 MeV corresponding to 12 a.m.u. (1 a.m.u. is 931.5 MeV).¶

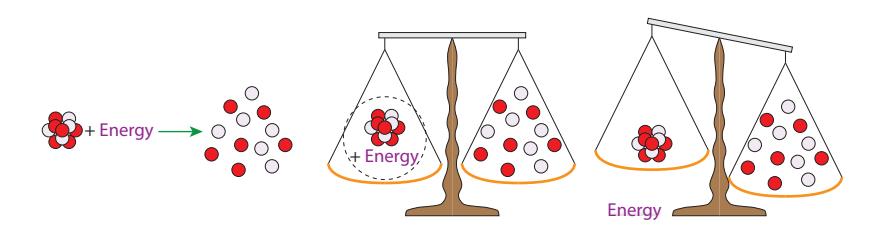

In practice, and perhaps surprisingly, atoms (nuclei) weigh less than the sum of their parts due to binding energy. In order to rip a nucleus completely apart and move all the nucleons far from each other, energy must be put in (left part of Figure 15.9). And any change in energy is accompanied by a change in mass, via . All the energy that must be injected to completely dismantle the nucleus weighs something! So the mass of the individual pieces after dismantling the nucleus is effectively the mass of the original nucleus plus the mass-equivalent of all the energy that was put in to tear it apart (middle panel of Figure 15.9). Therefore, binding energy effectively reduces the mass of a nucleus, which we will now explore quantitatively.

A careful look at Figure 15.4 reveals that lighter stable nuclei (graysquares) at the lower left of the chart have a mass a little larger than the corresponding mass number, but by the upper right—around oxygen the mass has edged just lower than 퐴. Table 15.3 shows this trend, confirmable in Figure 15.4 for the first four nuclides in the table. The difference between mass and 퐴 is most negative around iron, then turns around and becomes positive again for heavy elements like uranium.

What is going on here? If the mass of a nucleus were just the sum of its parts, we would expect the total mass to just track linearly as we add more pieces. In fact, if we try to build a neutral carbon atom out of 6 protons, 6 neutrons, and 6 electrons, the sum, according to Table 15.4, should be 12.099 a.m.u., not 12.000. The discrepancy is due to nuclear binding energy, as was introduced in Figure 15.9.

| Particle | a.m.u. | 10-27 kg | MeV/ c 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| proton | 1.0072765 | 1.6726219 | 938.2720882 |

| neutron | 1.0086649 | 1.6749275 | 939.5654205 |

| electron | 0.00054858 | 0.000911 | 0.510999 |

| (a.m.u.) | 1.0000000 | 1.660539 | 931.494102 |

Nuclear binding energy is incredibly strong15 and is able to overpower the natural electric repulsion between positively charged protons and stick them together in an unwilling bunch. The strong nuclear force only acts over a tiny range within about 10-15 m:16 it is very powerful

15: . . . relating to what we call the strong nuclear force

16: The whole atom is around 10-10 m inFigure 15.9: One must add energy to overcome nuclear binding energy in order to bust up a nucleus into its constituent nucleons (left). Thus, the collective mass of a nucleus plus the mass associated with the energy it takes to break it apart (via ) must be equal to the sum of the masses of the constituent parts (middle). Therefore, if we compare the mass of the nucleus alone (removing the energy’s mass from the scale) it must be less than the mass of the loose collection of nucleons (right).Table 15.3: Example mass progression.

| Nuclide | A | mass (a.m.u.) |

|---|---|---|

| 2H | 2 | 2.014 |

| 4He | 4 | 4.003 |

| 12C | 12 | 12.000 |

| 16O | 16 | 15.995 |

| 56Fe | 56 | 55.935 |

| 235U | 235 | 235.044 |

Table 15.4: Constituent masses of atomic building blocks, expressing the same basic thing in three common units systems.

scale

on short length scales, but ceases to operate much beyond the confines of the nucleus. Think about binding energy this way: if we tried to pry a proton or a neutron (nucleon, generically) away from a nucleus, we would encounter a very powerful force opposing the action. But let’s say we persist, and do work in extracting the nucleon by the usual recipe of force times distance. It is so much work, in fact, that Δ퐸 = Δ푚푐2 becomes relevant, measurably altering the mass.

Table 15.5 walks through some example calculations, one of which is traced in Example 15.3.2. Because the 1H nuclide is just a lone proton, it has no binding energy.

| Nucleus | actual | (MeV) | MeV per nucleon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H | 1.007825 | 1.007825 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2H | 2.016490 | 2.014102 | 0.002388 | 2.22 | 1.11 |

| 4He | 4.032980 | 4.002603 | 0.030377 | 28.29 | 7.07 |

| 12C | 12.09894 | 12.000000 | 0.098940 | 92.16 | 7.68 |

| 56Fe | 56.46340 | 55.934942 | 0.528447 | 492.25 | 8.79 |

| 235U | 236.9590 | 235.043920 | 1.915065 | 1783.85 | 7.59 |

Example 15.3.2 Following the entry in Table 15.5 for Fe 56 , we first multiply the individual proton, neutron, and electron masses from Table 15.4 by the 26 protons, 30 neutrons, and 26 electrons comprising Fe 56 to get a sum-of-parts value of 56.46340 a.m.u..

The actual mass, as it appears for Fe 56 in the Chart of the Nuclides is 55.934942 a.m.u., which is smaller by 0.528447 a.m.u.18 18: These numbers also appear in Table

Since 1 a.m.u. is kg, we can convert this mass difference into kilograms, then multiply by , where m/s to get the associated energy in units of Joules. Traditionally, nuclear physics adopts a more convenient scale of electron-volts, and in particular, the MeV.19 To get our mass-energy difference from Joules to MeV, we divide by J/MeV, and this is the 492 MeV number appearing in the column of Table 15.5. 19: 1 MeV is 106 10-19 J (Sec. 5.9; pFinally, we divide by the number of nucleons in the nucleus—퐴 = 56 in this case—to determine how much binding energy is present per nucleon—the significance of which will soon become clearer.

Therefore, the difference between the sum-of-parts mass and actual nucleus mass in Table 15.5 provides a measure of how much binding energy holds the nucleus together.20 20: . . . thus how much energy would need

Notice that the first entry in Table 15.5 for the single-proton hydrogen atom has no binding energy in the nucleus: the lonely proton has no other nucleon to which it might bind. But deuterium ( H) has a proton and a neutron, held together by 2.2 MeV of binding energy. The binding entire nucleus, as in Figure 15.9© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

Grab a calculator and follow Example 15.3.2 yourself!

Table 15.5: Example nuclear binding energy calculations. The second column is the simple sum of masses of protons, neutrons, and electrons, per Table 15.4. Next is measured mass, then the difference. The difference is re-cast in MeV, representing the total binding energy of the nucleus, inexorably rising with the size of the nucleus. The final column divides by the mass number to get binding energy per nucleon, which peaks around iron. See Example 15.3.2 to understand how these numbers are computed.

17 17: Find this in Table 15.5.

eV, and 1 eV is 1.6022 × 10−19 J (Sec. 5.9; p. 78).

to be supplied to completely unbind the

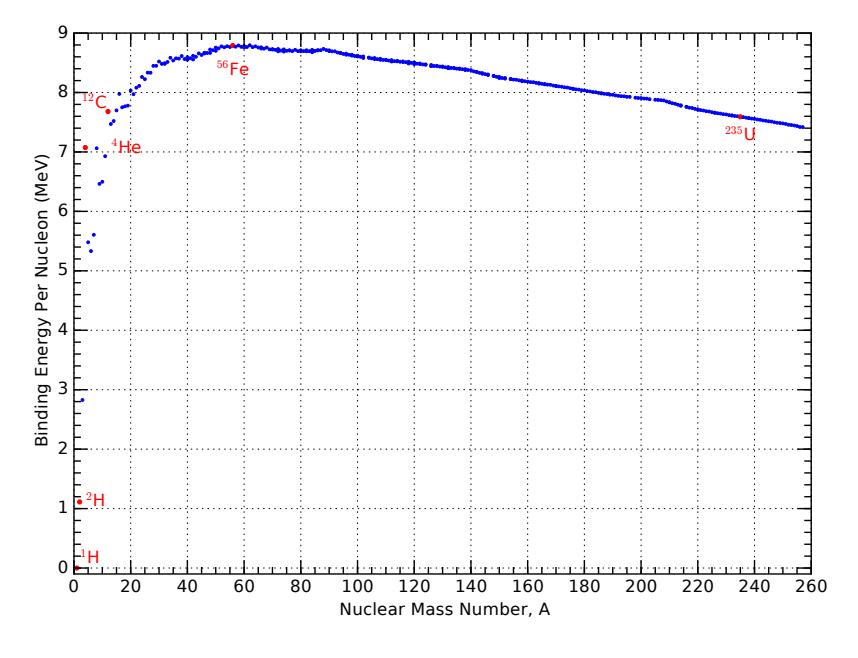

energy per nucleon in the last column of Table 15.5 starts out small, but soon settles to the 7–9 range for most of the entries. It is extremely insightful to plot the binding energy per nucleon as a function of the nucleon mass number, 퐴, which we do in Figure 15.10.

Figure 15.10: Binding energy per nucleon as a function of total mass number, 퐴. The nuclei featured in Table 15.5 are indicated as red points. Note in particular that Fe 56 sits at the peak of the curve. Fusion operates from left to right, building larger nuclei, and fission goes from right to left, tearing apart nuclei. Only actions that climb this curve are energetically favorable, meaning that fusion is profitable on the the left-hand side, and fission makes sense on the right: each driving toward the peak binding energy per nucleon.

The value of Figure 15.10 is hard to over-emphasize. Key take-aways are:

- Most nuclei are at around 8 MeV per nucleon, meaning that it would take an average of about 8 MeV of energy to rip out each member (proton or neutron) from a nucleus;

- The peak is at Fe 56 , 21 meaning that this is the most tightly bound nucleus;22

- The slope on the left side is much steeper than the slope on the right side, after the peak, which speaks to why fusion (building from small to big) is more potent than fission (tearing apart very massive nuclei);

- Fusion in stars does not build elements beyond the peak around iron, since to go beyond the peak is not energetically favorable.

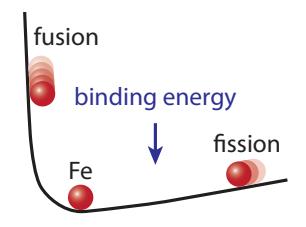

It can be helpful to think of Figure 15.10 upside-down, as in Figure 15.11, turning the iron “peak” into a trough. A ball will roll toward and settle near the bottom of the trough, which is what both fusion and fission do, but from opposite directions.

15.415.4 Fission¶

Having covered some fundamentals, we are ready to tackle aspects of nuclear energy. Really it is very simple. Enough nuclear material in a 21: Actually, Ni 62 wins by a hair at 8.795 MeV/nuc, but is somewhat overlooked because it is only 0.006% as abundant as Fe 56 whose binding energy per nucleon is essentially tied for the top at 8.790 MeV/nuc.

22: A peak exists because nucleons initially find advantage in binding together, but ultimately the increasing number of mutuallyrepelling protons makes the environment less appealing for larger nuclides.

Figure 15.11: Turning the binding energy curve upside-down makes it easier to conceptualize fusion and fission driving toward the most tightly bound point (iron), like a ball might roll.

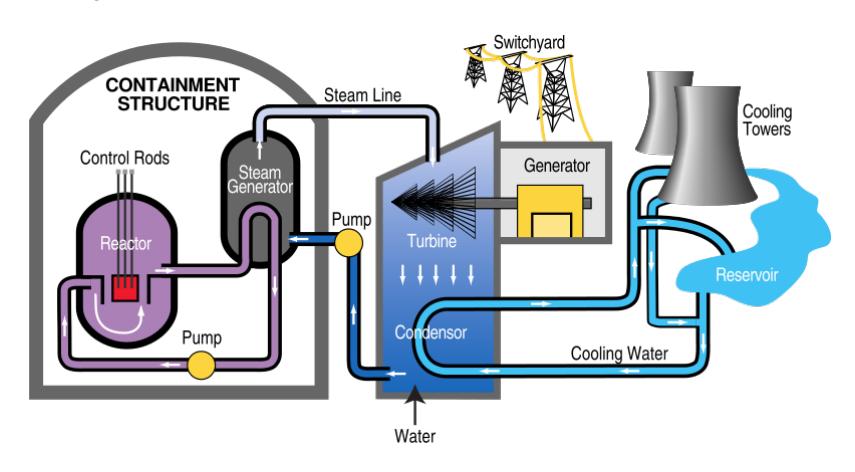

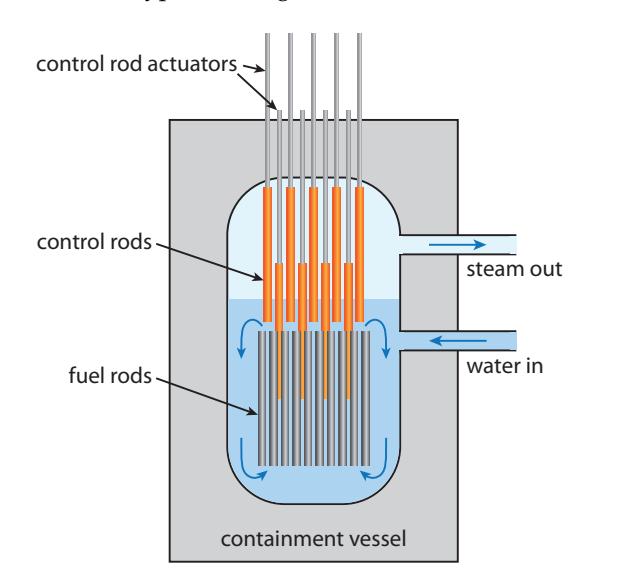

small space will get hot, for reasons detailed below. The heat is used to boil water into high-pressure steam, which then turns a turbine and generator (Figure 15.12). Note that a nuclear fission plant has much in common with a coal-fired power plant, as evidenced by the similarity of Figure 15.12 to Fig. 6.2 (p. 90). Only the source of heat is much different in origin.

Figure 15.12: Typical nuclear power plant design, bearing much resemblance to the generic scheme from Figure 6.2. Details on the reactor core will follow in Section 15.4.4. Source: TVA.

15.4.115.4.1 The Basic Idea¶

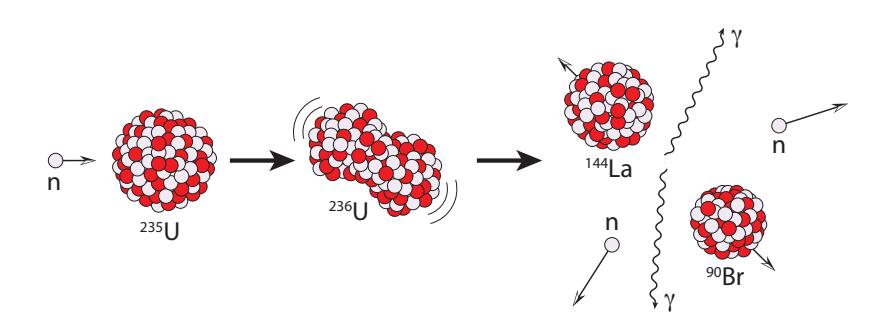

Out of all the nuclides, three are amenable for use in a fission reactor. Two are isotopes of uranium: and ; and one is plutonium: . Of these, only is found in nature, so we will concentrate on this one, returning later to the other two when we talk about breeder reactors in Section 15.4.4.2.What makes 235U (and the other two) special is that a slow23 neutron—one just bumping around at a speed governed by the local temperature, and thus called a thermal neutron—can walk up to and stick24 to the nucleus and cause it to split into two large chunks—depicted in Figure 15.13. Other nuclei would not break up, just accepting the new neutron and possibly converting a neutron to a proton via β− decay.

When the nucleus breaks up, the pieces fly out at high speed, carrying kinetic energy that will be deposited in the local material as they bump tends to bounce rather than stick to the nucleus.

24: No forces prevent a neutron from approaching a nucleus. Happening to hit the tiny nucleus is the only barrier.

Figure 15.13: Fission schematic for 235U, showing one of many possible outcomes—in this case 90Br and 144La plus two neutrons (an example case treated in detail in the text). The intermediate state, 236U, created when 235U absorbs a neutron, is highly unstable and will spontaneously break into (always) two different-size large fragments (“daughter” nuclei) and perhaps some extra neutrons. Gamma rays and kinetic energy (high-velocity fragments) are also released. Note that at each stage, the total number of nucleons is always 236.their way to a halt. Gamma rays25 are also released. By catching all of 25: . . . very high energy photons this energetic output, the surrounding material gets very hot and can be used to make steam.

15.4.1.115.4.2 Chain Reaction¶

As we have seen, in order to get fission to happen, we need and some wandering neutrons. Once fission commences, the breakup of the nucleus usually “drips” a few spare neutrons, like crumbs left after cutting a piece of bread. The left-over neutrons provide a replenished source of neutrons ready to initiate more fission events. Now the door is open for a chain reaction, in which the neutrons produced by the fission events are the very things needed to stimulate additional fission events.When the nucleus splits, any extra neutrons come out “hot” (high speed), which tend to bounce off uranium nuclei without sticking. They need to be slowed down, which is accomplished by a moderator: basically light atoms26 that can receive the neutron impact as a sort of damping medium. Then the main trick is to prevent a runaway that could occur if too many neutrons become available; in which case it’s a party that can get out of control. So nuclear plants employ control rods containing materials particularly effective at absorbing (trapping) neutrons. The colors of the lower halves of some squares in the Chart of the Nuclides (Figure 15.4) indicate neutron capture cross section. Boron ( ) is a favorite choice to soak up neutrons and tame (or even halt) the reaction. The goal is to maintain a chain reaction that produces a net balance of exactly one unabsorbed slow neutron per fission event, available to attach itself to a waiting 235U nucleus.### 15.4.3 Fission Accounting

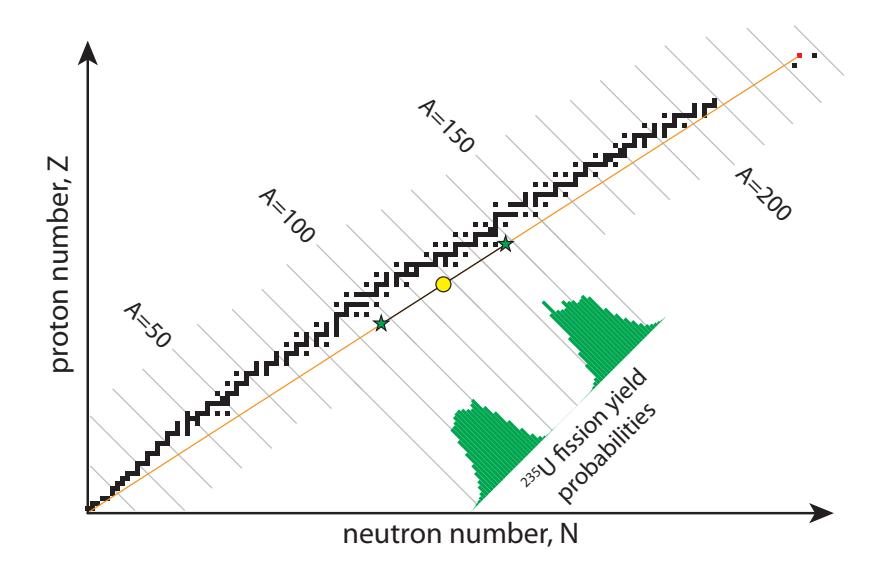

The nucleus (uranium in the present discussion) always breaks up into two largish pieces, possibly accompanied by a few liberated spare neutrons. Because of the way the track of stable elements curves on the Chart of the Nuclides, the resultant pieces are likely to be neutron rich, to the right of the stable nuclei. To understand this, refer to Figure 15.14 and the associated caption.

The math always has to add up: nucleons are not created or destroyed during a fission event. They just rearrange themselves, so the total number of neutrons stays the same, as does the total number of protons. After the split, 훽 − decays will carry out flavor changes, but we’ll deal with that part later.

25: ...very high energy photons

form of graphite

Example 15.4.1 If one of the two fragments from the fission of a nucleus ( ) after adding a thermal neutron winds up being ( ), what is the other nucleus going to be?The other fragment will preserve total proton count, so , and as such is destined to be the element lanthanum. Which isotope of lanthanum is produced depends on how many neutrons escape the split. Table 15.6 summarizes the particle counts of the various players.If no spare neutrons are left over, the lanthanum must have neutrons,27 in which case its mass number will be , so 146La. If two neutrons are set free, then the lanthanum will only keep 87 neutrons and be 144La, as depicted in Figure 15.13.Typically, about 2–3 neutrons are left out of the final fragments, and can go on to promote additional fission events in the chain reaction.

| 235U | 90Br | 146La | 145La | 144La | 143La | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 235 | 90 | 146 | 145 | 144 | 143 |

| Z | 92 | 35 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 |

| N | 143 | 55 | 89 | 88 | 87 | 86 |

| n | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

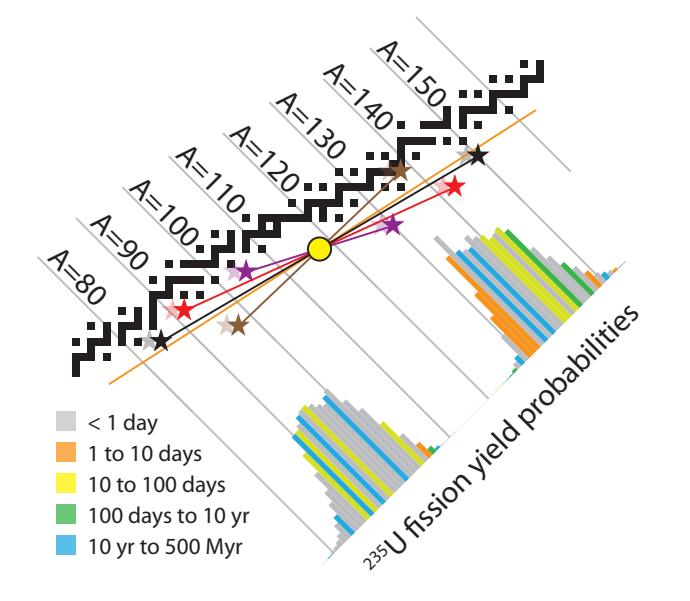

Being a probabilistic (random) process, each fission can result in a large set of possible “daughter” nuclei—only one set of which was explored in Example 15.4.1. As long as the masses all add up, and the two-hump probability distribution in Figure 15.14 is respected, anything goes. In other words, we have no control over exactly what pieces come out. Figure 15.15 provides a graphic illustration of four different possible pairs of daughter fragments. The counting requirement is satisfied by having the products located diametrically opposite from the 235U midpoint (yellow circle). The positions of the stars will distribute along -values© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; *Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.;* Freely available at: *https://

Table 15.6: Possible outcomes for Example 15.4.1 if we set one of the daughter particles to be bromine-90, forcing the other daughter to be lanthanum. Different isotopes of lanthanum will result for differing numbers of spare neutrons left after the break-up (last row).according to the probability distribution (multi-colored histogram). Note the completely distinct peaks, conveying that virtually every fission event results in just two fragments: one bigger and one smaller. At least that aspect of fission is predictable, even if we can’t say precisely which nuclei will be left after an individual fission event.

Let us now examine the energetics, using the result from Example 15.4.1, in which 235U breaks into 90Br and 144La, plus two spare neutrons.28 To be explicit, the reaction we will trace is 28: . . . also matching the scenario in Figure

| Constituent/Stage | mass (a.m.u.) | mass (MeV/ ) |

|---|---|---|

| 235U | 235.04392 | 218,942.0 |

| n | 1.00866 | 939.6 |

| input mass | 236.05259 | 219,881.6 |

| 90Br | 89.93069 | 83,769.9 |

| 144La | 143.91955 | 134,060.2 |

| 2n | 2.01733 | 1,879.1 |

| output mass | 235.86757 | 219,709.3 |

| mass change | 0.18502 | 172.3 |

The masses of each piece, according to the Chart of the Nuclides, appear in Table 15.7. Again, we find that the mass sums don’t equal: the final parts are lighter than the inputs. The fission managed to lose 0.185 a.m.u. of mass, corresponding to 172 MeV of energy (via ; see Example 15.3.1). That’s a 0.08% change in the mass, and converts to an energy density of roughly 17 million kcal/g, making the process over a million© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

Figure 15.15: Various fission product outcomes are possible, indicated here by four sets of colored star pairs and connecting lines. The average position of each pair is the yellow circle (the stars are diametrically opposite the circle), which guarantees that the total number of neutrons and protons is unchanged from the parent nucleus to the daughter nuclei. To the extent that additional neutrons are left behind like crumbs, the stars will displace to the left of their indicated positions a bit, as hinted by the lighter-shaded “ghost” stars, whose offsets from the nominal star positions will also vary depending on how many neutrons are left out of the two final fragments. The coloring of the histogram indicates radioactive lifetime for the decay chain of a neutron-rich fragment at each mass number, matching the half-life color scheme used in Figure 15.4.

15.13 and the penultimate column of Table 15.6

Table 15.7: Mass details of Eq. 15.2, tracking before and after masses in both a.m.u. and MeV units. The input mass of around 236 a.m.u. is reduced by about 0.185 a.m.u., or 0.08%.

times more energy–dense than our customary ∼ 10 kcal/g chemical energy density. See Box 15.3 for an example of how to compute this.

15.4.1.1.1Box 15.3: Nuclear Energy Density¶

The example corresponding to Table 15.7 is said to correspond to 17 million kcal/g, but how can we get here? The mass change of 0.185 a.m.u. corresponds to a mass in kilograms of 3.07 10-28 kg, according to the conversion that 1 a.m.u. is 1.6605 10-27 kg (Table 15.4). Multiply this by to get energy in Joules, yielding 2.76 10-11 J.29 In terms of kcal, we divide by 4,184 J/kcal to find that this fission event yields 6.6 10-15 kcal. 29: This result, by the way, is the same as 172.3 MeV in Table 15.7 using the conversion that 1 MeV is 1.6022 10-13 J.We now just need to divide by how many grams of “fuel” we supplied, which is 236.05 a.m.u. (Table 15.7), equating to kg, or g. Now we divide kcal by g to get kcal/g. Blows a burrito out of the water.Example 15.4.2 Considering that the average American uses energy at a rate of 10,000 W, how much U 235 per year is needed to satisfy this demand for one individual?

Since we have just computed the energy density of 235U to be 17 × 106 kcal/g (Box 15.3), let’s first put the total energy in units of Joules, multiplying 104 W by 3.155 × 107 seconds in a year and then dividing by 4,184 J/kcal to get kilocalories. The result is 75 million kcal, so that an American’s annual energy needs could be met by 4.5 g30 of 235U. That translates to about a quarter of a cubic centimeter, or a small pebble, at the density of uranium. Pretty amazing!We can take a graphical shortcut to all of Section 15.4.3, which hopefully will tie things together in an instructive way.

Example 15.4.3 Refer back to Figure 15.10 (and/or Table 15.5) to see that 235U has a binding energy of about 7.6 MeV per nucleon. Where we end up, around and , the binding energies per nucleon are around 8.7 and 8.4 MeV/nuc at these locations, respectively.Multiplying the binding energy per nucleon by the number of nucleons provides a measure of total binding energy: in this case 1,790 MeV for 235U, about 825 MeV for the daughter nucleus around , and 1,175 MeV for .31 Adding the latter two, we find that the fission products have a total binding energy around 2,000 MeV, which is greater32 than the 235U binding energy by about 210 MeV—somewhat close to the 172 MeV computed for the particular example in Table 15.7.

31: ; ; and

32: Binding energy reduces mass, so larger binding energy means lighter overall mass.The graphical method got us pretty close with little work, and hopefully led to a deeper understanding of what is going on. The rest of this

172.3 MeV in Table 15.7 using the conversion that 1 MeV is 1.6022 × 10−13 J.

kcal/g is 4.5 g.

31: 7.6 x 235; 8.7 x 95; and 8.4 x 140

binding energy means lighter overall mass.

paragraph explains the discrepancy, but should be considered nonessential reading. The fission process typically results in a few spare neutrons. Each left-over (unbound) neutron deprives us of at least 8 MeV in unrealized binding potential,33 33: Each missing neutron deprives us of and the subsequent 훽 − decays from the neutron-rich daughter nuclei to stable nuclei also release energy not accounted in Table 15.7. Both of these contribute to the shortfall in comparing 172 MeV to 210 MeV, but even without this, we got a decent estimate just using the graph in Figure 15.10.

15.4.1.215.4.4 Practical Implementations¶

As we saw above, nuclear fission involves getting fissile nuclei—generally U 235 —to split apart by the addition of a neutron. The following criteria must be met:

- presence of nuclear fuel ( U 235 );

- presence of neutrons, provided as left-overs from earlier fission events;

- a moderator to slow down neutrons that emerge from the fission events at high speed;

- a high enough concentration of nuclear fuel that the slowed-down spare neutrons are likely to find fissile nuclei;

- neutron absorbers in the form of control rods that can be lowered into the reactor and act as the main “throttle” to set reaction speed (thus power output), and also prevent a runaway chain reaction;

- a containment vessel to mitigate radioactive particles (gamma rays, high-speed electrons and positrons) from escaping to the environment.

Figure 15.16 shows a typical configuration.

Figure 15.16: Typical boiling water reactor design. A thick-walled containment vessel holds water surrounding 235U fuel rods. The water acts as the moderator to slow neutrons and also circulates around the rods to carry heat away, boiling to form steam that can run a standard power plant. Control rods set the pace of the reaction based on how far they are inserted into the spaces between fuel rods. Extra control rods are poised above the reactor core ready to drop quickly into the core in case of emergency—suddenly bringing the chain reaction to a halt.

more than the standard ∼8 MeV per nucleon, as neutrons have no penalty for repulsive electric charge. The 8 MeV per nucleon is an average over protons and neutrons.

In the design of Figure 15.16, called a boiling water reactor, the water acts as both the neutron moderator and the thermal conveyance medium. Nuclear fuel (uranium) is arranged in fuel rods, providing ample surface area and allowing water to circulate between the rods to slow down neutrons and carry the heat away. Neutron-absorbing control rods usually containing boron—set the reaction speed by lowering from the top.34 An emergency set of control rods can be dropped into the core in a big hurry to shut down the reactor instantly if something goes wrong. When the emergency rods are in place, neutrons have little chance of finding a 235U nucleus before being gobbled up by boron.34: . . . always this direction, so that gravityAs of 2019, the world has about 455 operating nuclear reactors, amounting to an installed capacity of about 400 GW.35 35: From this, we glean that reactors aver-The average produced power not all are running all the time—was just short of 300 GW. The thermal equivalent would be approximately three times this, or 1 TW out of the 18 TW we use in the world. So nuclear is a relevant player. See Table 15.8 for a breakdown of the top several countries, Fig. 7.7 (p.109) for nuclear energy’s trend in the world, and Fig. 7.4 (p.107) for the U.S. trend.

| Country | # Plants | GW inst. | GW avg. | % elec. | global share (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. | 95 | 97 | 92 | 20 | 31 |

| France | 56 | 61 | 44 | 71 | 15 |

| China | 49 | 47 | 38 | 5 | 13 |

| Russia | 38 | 28 | 22 | 20 | 8 |

| Japan | 33 | 32 | 8 | 8 | 3 |

| S. Korea | 24 | 23 | 16 | 26 | 5 |

| India | 22 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| World Total | 455 | 393 | 295 | 11 | 100 |

Nuclear plants only last about 50–60 years, after which the material comprising the core becomes brittle from exposure to damaging radioactivity and must be decommissioned. The median age of reactors in the U.S. is 40 years, and all but three are over 30 years old. Additional challenges will be addressed in the sections that follow.

When nuclear energy was first being rolled out in the 1950s, the catch phrase was that it would be “too cheap to meter,” a sentiment presumably fueled by the stupendous energy density of uranium, requiring very small quantities compared to fossil fuels. The reality has not worked out that way. Today, a 1 GW nuclear power plant may cost $9 billion to build [102] [102]: Union of Concerned Scientists (2015), . That’s $9 per Watt of output power, which we can compare to the cost of a solar panel, at about $0.50 per W (Fig. 13.16; p. 215), or utility-scale installation at $1 per Watt [89]. While it seems that solar36 36: Recall, for context, that solar is not wins by a huge margin, the low capacity factor of solar reduces average power output to 10–20% of the peak rating, depending on location. Meanwhile, nuclear reactors tend to run steadily 90% of the time—the off-time used for maintenance and fuel loading. So nuclear fission costs about $10 per delivered Watt, while solar panels are $2.5–5 per delivered

does the pulling rather then relying on some other drive force

age roughly 1 GW each.

Table 15.8: Global nuclear power in 2019 [101], listing number of operational plants, installed capacity, average generation for 2019 (Japan currently has stopped a number of its reactors), percentage of electricity (not total energy), and fraction of global production (these 7 countries accounting for over 75%). Notice the close match between number of plants and GW installed for most countries, indicating that most nuclear plants deliver about 1 GW.

The Cost of Nuclear Power

among the cheaper energy resources. Like solar, nuclear power is dominated by up-front costs, rather than fuel cost.

Watt and installed utility-scale systems are $5–10 per Watt. In short, nuclear power is not an economic slam dunk.

15.4.1.2.115.4.4.1 Uranium¶

So far, we have ignored a crucial fact. Only 0.72% of natural uranium on Earth is the fissile 235U flavor. The vast majority, 99.2745%, is the benign 238U.37 The ratio is about 140:1, so for every 235U atom pulled out of the ground, 140 times this number of uranium atoms must be extracted. The origin of the disparity is a story of astrophysics and eons, covered in Box 15.4.

37: A trace amount, 0.0055%, is in 234U.#### Box 15.4: Origin of Uranium

The Big Bang that formed the universe produced only the lightest nuclei. By-and-large, the result was 75% hydrogen (1H) and 25% helium (4He). Deuterium (2H) and 3He were produced at the 0.003% and 0.001% levels, respectively, and then the tiniest trace of lithium. No carbon or oxygen emerged, which must be “cooked up” via fusion in stars.Fusion in stars does not “climb over” the peak of the binding-energy curve in Figure 15.10, so stops in the vicinity38 38: Iron has 푍 = 26; stars tend not to proof iron. From where, then, did all of the heavier elements on the periodic table derive? Exploding stars called supernovae and merging neutron stars appear to be the origin of elements beyond zinc.

The relative abundance of 235U and 238U on Earth can be explained by their different half-lives of 0.704 Gyr and 4.47 Gyr, respectively. Even if starting at comparable amounts, most of the 235U will have decayed away by now. Solving backwards39 to when they would have been present in equal amounts yields about 6 Gyr, which is older than the age of the solar system (4.5 Gyr) and younger than the universe (13.8 Gyr). This is a reasonable result for how old the astrophysical origin might be—allowing a billion years or so for the material to coalesce in our forming solar system.

Uranium is not particularly abundant. Table 15.9 provides a sense of how prevalent various elements are in the earth’s crust. Uranium is more abundant than silver, but the useful 235U isotope is four times rarer than silver, and only about 5 times as abundant as gold. Proven reserves of uranium [103] amount to 7.6 million (metric) tons available, and we have used 2.8 million metric tons to date. The implication is that we could continue about 3 times longer than we have gone so far on proven reserves. But nuclear energy has played a much smaller role than fossil fuels, so maybe this isn’t so much. [103]: (2020), List of Countries by Uranium ReservesEvaluating the uranium reserves in energy terms is the most revealing

37: A trace amount, 0.0055%, is in $^{234}$U.

duce elements beyond zinc ( ) by fusion.and process as carbon-14 radioactive dating, but using much longer half life nuclei to date Earth’s building blocks!

Reserves

| Element | Abund. | Element | Abund. | Element | Abund. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| silicon | 282,000 | carbon | 200 | thorium | 9.6 |

| aluminum | 82,300 | copper | 60 | uranium | 2.7 |

| iron | 56,300 | lithium | 20 | silver | 0.075 |

| calcium | 41,500 | lead | 14 | 235U | 0.02 |

| titanium | 5,650 | boron | 10 | gold | 0.004 |

approach. First, we take 0.72% of the 7.6 million tons available to represent the portion of uranium in the form of 235U. Enrichment (next section) will not separate all of the 235U, and the reactor can’t burn all of it away before the fuel rod is essentially useless. So optimistically, we burn half of the mined 235U in the reactor. Multiplying the resulting 27,300 tons of usable 235U by the 17 million kcal/g we derived earlier yields a total of J. Table 15.10 puts this in context against fossil fuel proven reserves from page 127. We see from this that proven uranium reserves give us only 20% as much energy as our proven oil reserves, and about 5% of our total remaining fossil fuel supply. If we tried to get all 18 TW from this uranium supply, it would last less than 4 years! This does not sound like a salvation.Proven uranium reserves would last 90 years at the current rate of use, so really it is in a category fairly similar to that of fossil fuels in terms of finite supply. To be fair, proven reserves are always a conservative lower limit on estimated total resource availability. And since fuel cost is not the limiting factor for nuclear plants, higher uranium prices can make more available, from more difficult deposits. Still, even a factor of two more does not transform the story into one of an ample, worry-free resource.#### 15.4.4.2 Breeder Reactors

In its native form, 235U is too dilute in natural uranium—overwhelmingly dominated by 238U—to even work in a nuclear reactor. It must be enriched to 3–5% concentration to become viable.40 Enrichment is difficult to achieve. Chemically, 235U and 238U behave identically. The masses are so close—just 1% different—that mechanical processes have a difficult time differentiating. Centrifuges are commonly used to allow heavier 238U to sink faster41 than 235U. But it’s inefficient and usually requires many iterations to work up higher concentrations. The process is also lossy, in that not all of the 235U finds its way to the enriched pile.42 40: Uranium bombs need at least 20% 235U concentration, but typically aim for 85% to be considered weapons grade. 41: ... in gaseous form. 42: Depleted uranium is defined as contain-But what if we could use the bulk uranium, 238U, in reactors and not only save ourselves the hassle of enrichment, but also gain access to 140 times more material, in effect? Doing so would turn the proven reserves of uranium into about 7 times more energy supply than all of our remaining fossil fuels. Well, it turns out that despite its not beingTable 15.9: Example material abundances in the earth’s crust, in parts per million by mass.

Table 15.10: Proven reserves, in energy terms.

| Fuel | 1021 J |

|---|---|

| Coal | 20 |

| Oil | 10 |

| Gas | 8 |

| 235U | 2 |

concentration, but typically aim for 85% to be considered weapons grade.41: ...in gaseous form

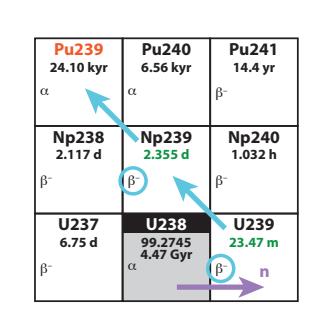

ing 0.3% or less in the form of 235U, which is not a huge reduction from the 0.72% starting point.one of the three fissile nuclei, we can convert43 into the fissile 43: ... called transmutation the following way.1. A 238U may absorb a wandering neutron to become 239U.- 2. U 239 , whose half life is 23.5 minutes, undergoes 훽 − to become Np 239 in short order.

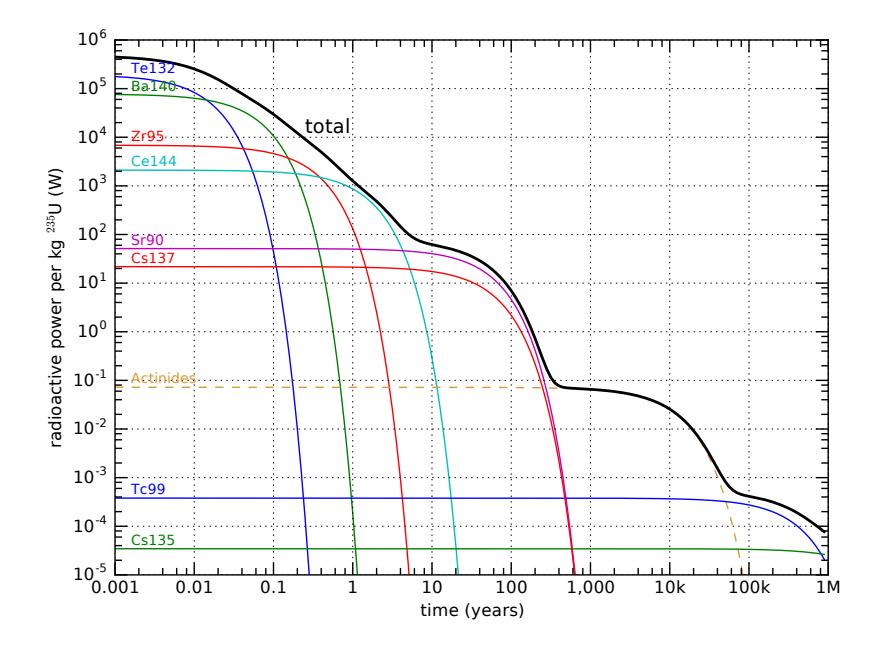

Figure 15.17 highlights this process in a simplified region of the Chart of the Nuclides, while Figure 15.18 shows complete details for the entire region around the fissile materials—the ones with red isotope names—which can be used to track the sequence outlined above.

Figure 15.17: Breeder route to 239Pu.

Figure 15.18: Chart of the Nuclides in the fission region. See also Figure 15.4 for the lower-left corner.The result is that sterile 238U can be turned into fissile 239Pu that can be used in fission reactors. This process of transmuting an inert nucleus into a fissile one is called breeding, and is how we get any plutonium at all.44 A nuclear reactor is a great place to introduce 238U to neutrons: both are already in attendance. In fact, breeding happens as a matter of course in a nuclear reactor: it is estimated that one-third of the fission 44: . . . e.g., for weapons

44: ...e.g., for weapons

energy in ordinary nuclear reactors comes from plutonium breeding and subsequent fissioning—without any extra effort. Special reactor designs enhance plutonium production, allowing the fuel rod to be “harvested” for plutonium. Usually, the plutonium is destined for use in weapons, but in principle reactors could be designed to efficiently produce and use plutonium from the U 238 feedstock. Downsides will be addressed in Section 15.4.6 on weapons and proliferation.

15.4.1.2.2Box 15.5: Thorium Breeding¶

Another form of breeding merits mention. Notice that thorium45 is more abundant than uranium in Table 15.9. But like 238U, it is not fissile. However, applying the breeding trick, the absorption of a neutron by 232Th ends up as 233U—the last of our three fissile nuclei—in about a month’s time. This provides an avenue for an even greater energy store than exists in 238U via breeding to 239Pu, by virtue of greater abundance. Unlike the plutonium route, thorium breeders are less susceptible to weapons and proliferation concerns.46 That said, thorium reactors are more complex than uranium reactors, so that technical hurdles have thus far prevented any commercial scale application of the technique, leaving us unclear whether thorium represents a viable nuclear path.

45: . . . of which 100% is the desired 232Th isotope

46: . . . although, radioactive waste is still problematic### 15.4.5 Nuclear Waste

As we saw in our description of the fission process, the fragments distribute over a range of masses in a randomized way (Figure 15.15). The results are generally neutron-rich, and will migrate toward stable elements via 훽 − decays over the ensuing seconds, hours, days, months, and years. Some will go fast, and some will take ages to settle, depending on half-lives. Radioactive waste is dangerous to be around because the high-energy particles (like sub-atomic “bullets”) spewing out in all directions can alter DNA, leading to cancer and birth defects, for instance.

The lighter of the two fission fragments has a 59% chance of landing on a stable nucleus within a day or so. For the heavier fragment, it’s a 45% chance. The rest get hung up on some longer half-life nuclide, and could remain radioactive for a matter of weeks or in some cases millions of years. The colors in the fission probability histograms in Figure 15.15 provide a visual guide for the mass numbers that reach stability promptly (gray) vs. those that get hung up for a long time (blue is more than 10 years). For example, the histogram element at 퐴 = 90 is blue because Sr 90 —discussed below—stands in the way of a fast path to stability.

45: ...of which 100% is the desired $^{232}$Th isotope

problematic

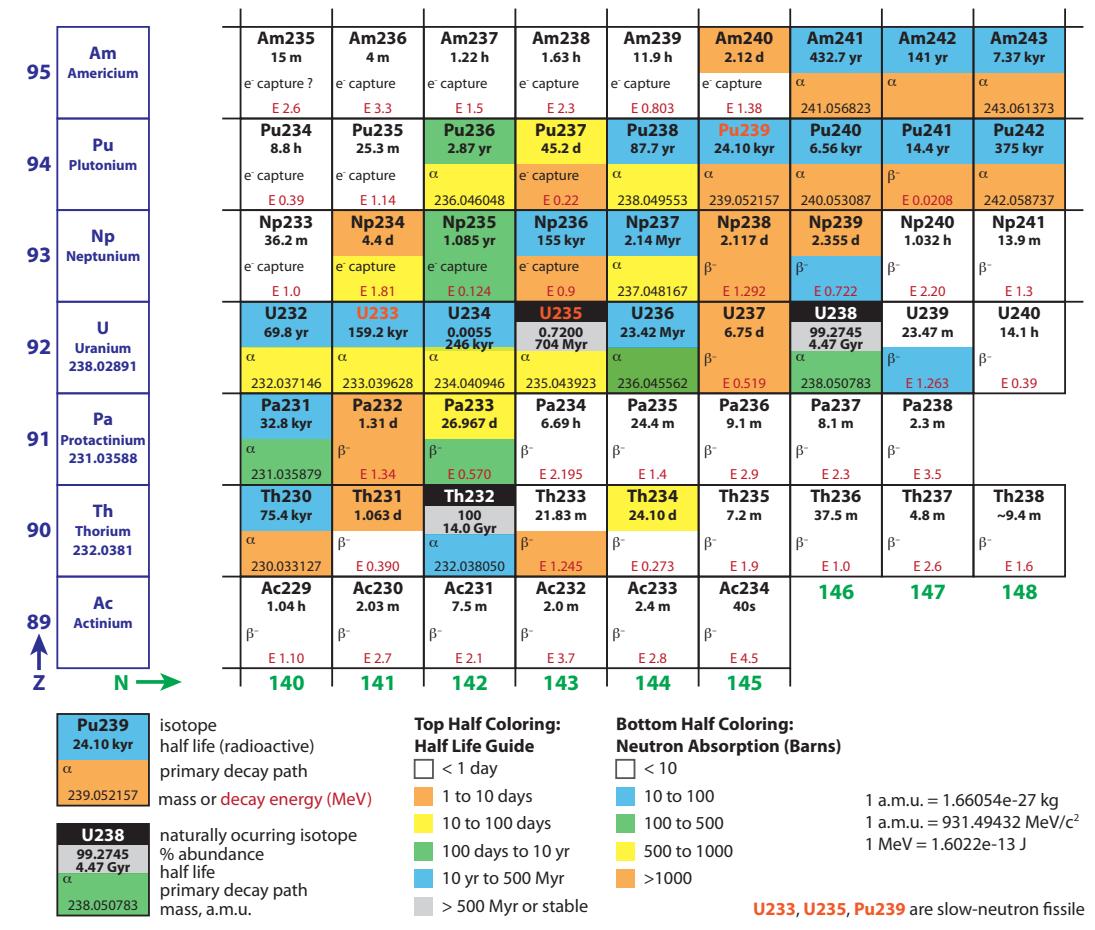

Figure 15.19: Decay activity of fragments from 1 kg of fissioned 235U over time, on a log–log plot. The vertical axis is the power of radioactive emission, in W, for a variety of relevant isotopes—each having their own characteristic half life. The black line at the top is the total activity (sum of all contributions), and some of the key individuals are separated out. The dashed line for actinides is an approximate representative indicator of the role played by heavy nuclides formed in the reactor by uranium absorption of neutrons. Minor tick marks are at multipliers of 2, 4, 6, and 8 for each axis. As a matter of possible interest, the exponential decays of each element on this log–log plot have the functional form of exponential curves drawn upside-down.

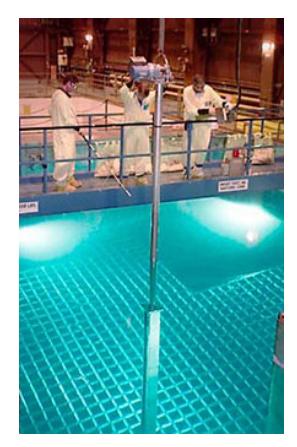

Figure 15.19 shows how the fission decays play out over time. For the first month or so out of the reactor, the spent fuel is really “hot” radioactively, but falls quickly as 95Zr and then 144Ce dominate around one year out. At about 5 years, the pair of 90Sr and 137Cs begin to dominate the output for the next few-hundred years. Some of the products survive for millions of years, albeit at low levels of radioactive power. In addition to the daughter fragments, uranium in the presence of neutrons transmutes into neptunium, plutonium, americium, and curium via neutron absorption and subsequent − decays, represented approximately and collectively in Figure 15.19 by a dashed curve labeled Actinides.47The bottom line is that fission leaves a trash heap of radioactive waste that remains at problematic levels for many thousands of years. When nuclear reactors were first built, they were provisioned with holding tanks—deep pools of water—in which to place the waste fuel until a more permanent arrangement could be sorted out (Figure 15.20). We are still waiting for an adequate permanent solution for waste storage, and the “temporary” pools are just accumulating spent fuel. Transporting the spent fuel is hazardous—in part because it could fall into the wrong hands and be used to make “dirty” bombs—and no one wants a nuclear waste facility in their backyard, making the problem politically thorny. On the technical side, it is difficult to identify sites that are geologically stable enough and have little chance of groundwater contamination. Underground salt domes offer an interesting possibility, but political challenges remain daunting.

47: Breeder reactors can “burn” the actinides, reducing some of the long-term waste threat, but will unavoidably still be left with all the radioactive fission products.

Figure 15.20: A spent fuel rod being lowered into a storage grid in a pool of water at a nuclear power plant. Source: U.S. DoE.

# 15.4.6 Nuclear Weapons and Proliferation

Nuclear bombs are the most destructive weapons we have managed to create. The first bombs from the 1940s were based on either highly enriched 235U or on 239Pu. For uranium bombs, the idea is shockingly simple. Two separate lumps of the bomb material are held apart until detonation is desired, at which point they are slammed together.48 It’s not the collision that creates the explosion, but a runaway process based on having a high concentration of fissile material and no neutron absorbers present to control the resulting chain reaction. The concept is critical mass. The combined lump exceeds the critical mass, and explodes.49

48: For plutonium, this process is fouled

49: Never stack lumps of fissile materialAs simple as nuclear weapons are to build, the bottleneck becomes

obtaining fissile material. Plutonium does not exist in nature, since its

24,100 yr half-life means nothing is left over from the astrophysical

processes that gave us uranium and thorium (Box 15.4). We only still

have the latter two thanks to their long half lives. So fissile material has to

start with uranium. But as we have seen, natural uranium is only 0.72%

fissile ( ). In order to be explosive, the uranium must be enriched

to at least 20% , and generally much higher (85%). Reactor fuel, at

3–5% will experience meltdown if the critical mass is exceeded,

but will not explode. Enrichment is technically difficult, and attempts

to acquire and enrich uranium are monitored closely. Often we hear of

countries pursuing uranium enrichment, claiming that they are only

interested in domestic energy production—a peaceful purpose. And it

is true that the first step in nuclear power generation is also enrichment.

So it is very difficult to ascertain true intentions. Once a country has

the ability to enrich uranium enough for a nuclear plant, they can in

principle keep the process running longer to arrive at weapons-grade

.While we worry about 235U falling into the wrong hands, perhaps more disturbing is 239Pu. Having a much shorter half-life than 235U (24 kyr vs. 704 Myr), it is more dangerous to handle.50 But plutonium is otherwise easy to deal with, since it requires no enrichment and can be chemically separated to achieve purity. It is the material of choice for nuclear weapons.

50: ... much higher rate of radioactive de-caySerious pursuit of breeder reactors effectively means manufacturing lots of plutonium, leading to proliferation of nuclear materials: it becomes harder to track and keep away from mal-intentioned groups. The world becomes more dangerous under a breeder program. Thorium breeding (Box 15.5) is less risky in this regard because the U prize is mixed with a ridiculously dangerous U isotope that puts plutonium to shame, so working with it is pretty deadly, which may deter would-be pursuit of this material by rogue groups.A related concern involves proliferation of the abundant radioactive waste from fission plants, which could be mixed into conventional explosives51 to radioactively contaminate a city or local region—poisoning 51: . . . called a "dirty bomb"by the presence of Pu, forcing a different approach in which a sphere below critical mass is imploded to create high density.together on a shelf, or a nasty surprise may50: ...much higher rate of radioactive de-cay51: . . . called a “dirty bomb”

water, food, and air. In short, nuclear fission carries many perils on a number of fronts.

15.4.215.4.7 Nuclear Safety¶

A properly operating nuclear facility actually emits less radioactivity than does a traditional coal-fired power plant! As is true for many materials mined from the ground, coal contains some small amount of radioactive elements found in the earth’s crust: principally thorium, uranium, and potassium. Lacking any shielding or protection, the exhaust from a coal plant distributes these products into the atmosphere. Nuclear plants, by contrast, have no exhaust,52 and carefully control the exposure to radioactivity.However, things can go wrong. The U.S. had a scare in 1979 when a six-month-old nuclear plant at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania (Figure 15.21) suffered a loss-of-cooling incident that resulted in severe damage to (meltdown of) the core. But the containment vessel held and no significant radioactivity was released to the environment. Workers at the plant received a dose equivalent to an extra 100 days of natural53 53: We are unavoidably exposed to radiaexposure. So we dodged a bullet.

Chernobyl was not so lucky in April 1986 when an ill-conceived test went sideways and resulted in an actual explosion of the core. This scenario was previously thought to be impossible, but it was a steam explosion, not a nuclear blast—so more like a “dirty bomb” that scattered radioactive material across the region. Thirty-one people died in the immediate aftermath, and about 200 people got acute radiation sickness. It is estimated that in the long term, 25,000 to 50,000 additional cancer cases will result, but this number is controversial and it is hard to tease Chernobyl-caused cancer/deaths apart from the much larger number of background cancer cases. The town of Chernobyl is still abandoned and only recently has begun to allow strictly limited incursions.

The most recent major accident was the Fukushima Daiichi plant in Japan following the Sendai earthquake in March 2011, resulting in the evacuation of 200,000 people and agricultural loss. The earthquake caused the three operating reactors to shut down (safely), while dieselfueled generators ran to power pumps maintaining cooling flow over the hot fuel rods. The core of a reactor is still very hot after fission stops and continues to generate heat as daughter nuclei decay, so cooling flow must be maintained or the core can melt. The ensuing tsunami54 ruined 54: . . . within 10 minutes of the earthquake the plan to keep the cores cool, as the generator rooms flooded, causing the cooling flow to fail. The cores of all three reactors melted down and hydrogen gas explosions created a major release of radioactivity. Perhaps in contrast to the Chernobyl plant, Fukushima was designed by General Electric and operated by a well-educated high-tech society. No one is exempt from risk when it comes to nuclear reactors.

plume of water vapor above them, but this is the result of evaporative cooling, and not exhaust in the usual sense.

tion in our daily lives from air, water, food, Earth, and the cosmos.

Figure 15.21: Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania. The two reactor cores are in the foreground of the larger cooling towers behind. Source: U.S. DoE.

54: ... within 10 minutes of the earthquake

15.515.4.8 Pros and Cons of Fission¶

Collecting the advantages and disadvantages of fission, we start with the positive aspects:

- I Nuclear fuel has extraordinary energy density, about a million times better than chemical energy density;

- I Nuclear fission is proven technology providing a substantial fraction of electrical energy at present;

- I Life-cycle CO2 emissions for nuclear fission is only 2% that of traditional fossil fuel electricity [68]; [68]: (2020), Life Cycle GHG Emissions

- I Breeder reactors could provide thousands of years of fuel, by way of uranium and thorium (undeveloped as yet).

And for the downsides:

- I Radioactive waste is dangerous for thousands of years, and no clear solution to its disposal or long-term storage has emerged.

- I Conventional uranium fission has limited fuel supply,55 55: . . . in the absence of breeder reactor measuring in decades;

- I Breeder reactors exacerbate the waste issue and promote proliferation of nuclear materials;

- I Development of nuclear energy technology prepares an easy step to immensely destructive nuclear weapons;

- I Accidents happen even to the best-managed reactors, the consequences often being severe for a region.

Nuclear fission is a complex topic that has compelling advantages and worrisome faults. Not surprisingly, attitudes are highly mixed. One survey [104] indicates that adults in the U.S. oppose building more nuclear plant by a slim 51% to 45%, while scientists overall favor advancing nuclear plants by a 2:1 margin,56 and physicists surveyed favored nuclear by 4:1. Scientists are much more likely to view climate change as a serious threat than the U.S. population as a whole, and therefore are likely to be attracted to energy resources that do not emit CO2. Of the physicists surveyed, it would be a mistake to assume that even the majority know the topic as thoroughly as it is covered in this chapter—given the degree of specialization within the field. Among those who understand the topic thoroughly57 it is almost certain you’d find a healthy split: those for whom the perils outweigh advantages, and those who are concerned enough about climate change to accept the “lesser of two evils,” and/or who are enthusiastic about the technology as a glowing example of our mastery over nature’s hidden secrets. [104]:

Pew Research (2015), “Elaborating on the Views of AAAS Scientists, Issue by Issue”

56: ... a clear, but not overwhelming, result

57: We might also acknowledge an intrinsic psychological appeal for complex topics that have been mastered: a sort of pride in the privileged comprehension that might transfer to warm feelings for the subject.# 15.5 Fusion

Given that fission has problems of finite uranium supply, radioactive waste, proliferation and weapons, and safety issues, its future is uncertain.

implementation

on the Views of AAAS Scientists, Issue by Issue"

56: . . . a clear, but not overwhelming, result

psychological appeal for complex topics that have been mastered: a sort of pride in the privileged comprehension that might transfer to warm feelings for the subject.

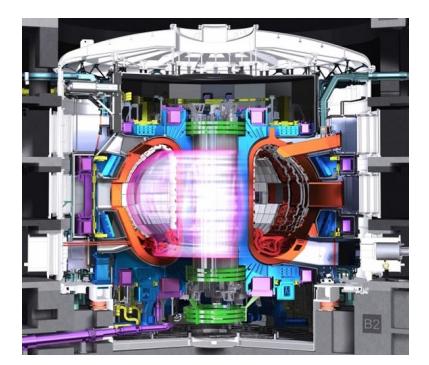

Fusion, on the other hand, is not plagued by most of these issues. It’s main problem is that it is incredibly difficult and has been in the research stage for 70 years. Other than that, it has many (virtual) virtues. To be clear, the world does not have and never has had an operational fusion power plant. It may belong to the future, but is not guaranteed to ever become practical.

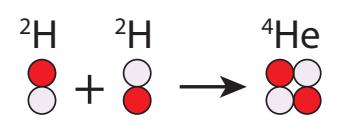

First, the basics. We have alluded to the fact that fusion builds from the small to the big. Putting four H nuclei together, at 1.007825 a.m.u. each and forming He at 4.0026033 a.m.u. leaves a difference of 0.0287 a.m.u.— 0.7% of the total mass—which amounts to 153 million kcal/g.58 This is almost ten times as large as the amount for fission (17 million kcal/g; Box 15.3), making it ten-million times more potent than chemical reactions. Recall that fusion’s better performance can be related to the steepness of the left-hand-side of the binding-energy-per-nucleon curve of Figure 15.10.

58: The calculation is that 0.0287 a.m.u. corresponds to kg, or J (26.7 MeV). We convert the Joules to kcal by dividing by 4,184, and then divide by the input mass in grams (4.03 a.m.u. times g/a.m.u.) to get 153 kcal/g. Starting with two deu-What makes fusion so difficult is that getting protons to stick together is incredibly hard. Their electric repulsion is so strong that they need to be approaching each other at a significant fraction of the speed of light (about 7%) in order to get within reach of the strong nuclear force that takes over at distances smaller than about 10-15 m. The corresponding temperature is a billion degrees.59

Even the center of the sun is “only” 16 million degrees. The sun has the advantage of being enormous, though. So even at a comparatively chilly 16 million degrees, some rare protons by chance will be going extra fast and have enough oomph to overcome the repulsion and stick together. It’s like winning the lottery against very long odds, but the sun is large enough to buy ample tickets so the process still happens often enough.60 We don’t have such a luxury in a terrestrial laboratory setting, so we need higher temperatures than what exists in the center of the sun!Using 2H nuclei (deuterons, labeled D) instead of 1H (protons) in what is called a D–D fusion reactor, allows operation at 100 million degrees instead of 1 billion. And colliding one deuteron with a triton61 (3H nucleus, labeled T; 12.3 year half-life), only requires 45 million degrees for a D–T fusion reactor. For this reason, only D–T fusion is currently pursued.For all three types, the relevant reactions62 are: 62: . . . allowing beta decays to change pro-

| p-p: | 1H + 1H + 1H + 1H → | 4He | + | 26.7 MeV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-D: | 2H + 2H → | 4He | + | 23.8 MeV | (15.3) |

| D-T: | 2H + 3H → | 4He + n | + | 17.6 MeV |

But the 45 million degrees required for D–T fusion is still frightfully hard to achieve. No containers will withstand temperatures beyond a few thousand degrees. Containment—or confinement—is the big challenge then. The multi-million degree plasma63 cannot be permitted to touch the qualifies as a plasma.

Figure 15.22: Fusion concept: helium from deuterium.

responds to Δ푚 = 4.8 × 10−29 kg, or 퐸 = Δ푚푐2 = 4.2 × 10−12 J (26.7 MeV). We convert the Joules to kcal by dividing by 4,184, and then divide by the input mass in grams (4.03 a.m.u. times 1.6605 × 10−24 g/a.m.u.) to get 153 kcal/g. Starting with two deuterium nuclei reduces energy yield a bit to to 137 kcal/g, and for deuterium-tritium reactions it’s down to 81 million kcal/g.

matter whether we specify Kelvin or Celsius, as the 273 degree difference is nothing compared to a billion degrees. The scales are therefore essentially identical here.

60: This is no accident: if the center were too cool, the sun would contract in the absence of radiation pressure until the center heated up from the compression and nuclear fusion ignited—just enough to hold off further contraction. It finds its own equilibrium right at the edge of fusion. In the case of the sun, all it takes is one out of every 1026 collisions to stick in order to keep the lights on.

61: If only the UCSD mascot were named after this triton. . .

tons to neutrons in the process

63: Plasma is a hot ionized gas where electrons are stripped off the nuclei. The sun

walls of the chamber, despite its constituents zipping around at speeds around 1,000 km/s! This feat can be sort-of managed via magnetic fields bending the paths of the fast-moving charged particles into circles. But turbulence in the plasma plagues attempts to confine the D–T mixture at temperatures high enough to produce fusion yield.

15.5.0.0.1Box 15.6: Successful Fusion¶

Note that besides stars as an example of successful fusion, we have managed to create artificial fusion in a net-energy-positive manner in the form of the hydrogen bomb. This is indeed a fusion device, but we could not call it controlled fusion. It actually takes a fission bomb (plutonium) right next to the D–T mixture in a hydrogen bomb to heat up the D–T enough to undergo fusion. It’s neat (and awful) that it works and is demonstrated, but it’s no way to run a power plant.

If a 45 million degree plasma could be confined in a stable fashion, the heat generated by the reactions64 64: . . . in the form of radioactive release could be used to make steam and run a traditional power plant—replacing the flame symbol in Fig. 6.2 (p. 90) with something much fancier. The scheme, therefore, requires first heating a plasma to unbelievable temperatures in order for the plasma to self-generate enough additional heat through fusion that the game shifts to one of keeping the plasma cool enough to produce a steady rate of fusion without blowing itself out. In this scenario, the heat extracted from the cooling flow makes steam. It’s the most elaborate65 65: Should we be proud if we succeed, or possible source of heat to boil water. It may be a bit like working hard to develop a light saber whose only use will be as a letter opener.

15.5.0.115.5.1 Fuel Abundance¶

Deuterium—an isotope of hydrogen—is found in 0.0115% of hydrogen,66 66: See the Chart of the Nuclides abundance information in Figure 15.4. which means that the occasional H2O molecule is actually HDO.67 Therefore sea water is chock-full of deuterium. The global 18 TW appetite would need deuterium atoms per year for D–D or each of deuterium and tritium atoms per year for D–T. Running with this latter number for the comparatively easier D–T reaction, we would need to process water molecules each year to find the requisite deuterium. This corresponds to 26 million tons of water, which is a cubic volume about 300 m on a side. Yes, that’s large, but the ocean is larger. Also, it corresponds to a volume of 0.16 billion barrels per year, which is about 200 times smaller than our annual oil consumption. Thus, the volume required should be not at all challenging.68 68: Ocean water is far easier to access than The ocean volume is 60 billion times larger than our 300-m-sided cube, implying that we have enough deuterium for 60 billion years. The sun will not live that long, so let’s say that we have sufficient deuterium on Earth.back to the plasma

embarrassed at the lengths we had to go to?

66: See the Chart of the Nuclides abun- dance information in Figure 15.4.

67: . . . one , one and one oxygen

underground oil deposits, after all.

Tritium, however, is essentially nowhere to be found, as it has a half-life of 12.3 years. We can generate tritium by adding a neutron to lithium and stimulating an α decay. So the question moves to how much lithium we have. Proven reserves are at about 15 million tons, currently produced at about 30,000 tons per year.69 We would need 2,300 tons70 of lithium per year to meet our tritium atom target (for 18 TW). In the absence of competition71 for lithium resources, the associated R/P ratio timescale is 6,500 years. Yes, that is a comfortably long time, but not eons. The thought is that this would buy time to solve the D–D challenge.# 15.5.2 Fusion Realities