19.1A Plan Might Be Welcome¶

Having discussed some of the human factors related to accepting and mitigating challenges, we now turn to the question of what humanity’s goal might be if we could collectively start rowing in the same direction.

First, we will have to assess the form that our actions have taken in the absence of a coherent plan. Next, we address challenges inherent in devising and adopting a roadmap for our future. Finally, a possible target is presented that bears consideration as we grapple with possible modes of human society going forward.

19.219.1 No Master Plan¶

The “adults” of this world have not established a global plan for peace and prosperity. This has perhaps worked okay so far: a plan hasn’t been necessary. But as the world changes from an “empty” state in which humans were a small part of the planet with little influence to a new “full” regime1 where human impacts are many and global in scale, perhaps the “no plan” approach is the wrong framework going forward.2

1: 96% of mammal mass on Earth humans and their livestock [121].

2: In rare cases, small islands likeMost decisions are made based on whether money can be made or saved in the short or intermediate term. The market then becomes the primary arbiter of what transpires, constrained only by a light touch of legal regulations and public sentiment. Earth and its ecosystems have little voice3 in our artificially-constructed societal framework—at least in the short term.Perhaps we are structuring our world exactly backwards. An attempt to put a monetary value on the earth and its intricate biological web—a web that by construction4 is exactly the foundation humans rely upon for survival—produces absurdly large numbers in the sextillions of dollars 4: . . . that humans evolved into1: 96% of mammal mass on Earth is now

2: In rare cases, small islands like Tikopia operated under plans to live within finite bounds. Now, Earth is effectively a small island and needs to shift to a “small-island” plan.

3: Consider whether a tree or a polar bear can sue a lumber or oil company.

4: ... that humans evolved into

Uh. Shouldn’t I have more pieces? Photo credit: Tom Murphy

(Box 19.1). In this context, the $100 trillion global annual economy is such a minuscule fraction of the value of the earth. Yet reflect on the question: which valuation drives almost all of our decisions?

19.2.0.1Box 19.1: Earth’s Dollar Value¶

How much would it cost to purchase a barren planet and then to layer atop it a complete, functioning ecosystem?5 Starting with the 5: . . . actually many connected ecosystems basics, the cost of rough rock, sand, or dirt in the U.S. bottoms out at about $5 per cubic yard.6 It is the very definition of “dirt cheap.” 6: . . . not including delivery We’ll upgrade the volume to a cubic meter7 for ease. The earth is roughly 1021 cubic meters in volume, so even if given a smoking deal on the materials at $1 per cubic meter, the price tag is in the sextillion dollar regime ($1021). The high central density of the earth makes the price tag even higher under the more sensible cost per ton,8 considering the 6 sextillion ton mass of the earth. This is an 8: . . . rather than by volume admittedly naïve way to price a planet, but it puts a scale on things.

A similarly simple calculation applies to minerals. Ignoring the material in the molten mantle, using crustal abundances and only the stuff in the 30 km crust under dry land,9 the continental crust contains $0.6 quintillion ( $ ) of silver, $3 quintillion in gold, $5 quintillion in copper, and $20 quintillion in nickel.10 Aluminum leaps up to $2 sextillion, but probably reflects the energy-intensive extraction process.By these estimates, the earth is already worth something in excess of $1021, and that’s before adding biology, whose billions of years of tuning under evolution is not something we even have the skill to replicate, let alone affix a price tag. Perhaps an evolved biology is more valuable than the raw materials. Given all the barren planets in the universe, an argument can be made that a biologically diverse planet would fetch a premium price. Comparing this to the global $1014 budget, the economy registers at less than a millionth the worth of the planet, yet all our decisions are made based on what is good for the tiny flea, ignoring the essential and much larger canine host.

As human actions on this planet close the door on one species after another, it is important to realize that we are losing an investment of millions upon millions of years of evolutionary fine-tuning that led to this splendid place we call home. The human race has set about to negligently, unwittingly destroy its home, showing essentially no regard for its worth.

19.2.1Box 19.2: Clueless Cat Analogy¶

In analogy, domestic cats cannot possibly comprehend why they should not be allowed to claw the sofa. To their minds, the sofa is

5: ...actually many connected ecosystems

6: ... not including delivery

7: . . . would cost 30% more, but we’ll ignore this small adjustment

8: . . .rather than by volume

the continental crust 9: . . . just 0.4% of Earth’s volume

kilogram, and according to crustal abundances in Table 15.9 (p. 258), gold is 4 parts per billion of the crust by mass. The crust in question has a volume of 4.4 × 1018 m3 and a mass around 1.3 × 1022 kg. The expected mass of gold is then about 5×1013 kg, and would cost $3 × 1018. Notice that the total values are amazingly close for these metals: rarer is more expensive in inverse proportion and thus in rough balance.

there, has always been there, feels “right” and good on their claws, and surely can serve no other purpose than to satisfy their urges. How could they possibly understand what it would cost to replace, or why we even care about the appearance to begin with? It would be an even better analogy if the cats’ very survival depended11 on maintaining an unspoiled sofa, in ways the cats could never grasp.

11: ... for instance, if their food source de-Maybe humans as a species are as clueless12 as the cats in Box 19.2 about their present actions. In some sense, this possibility provides a compelling reason to stop. If we can’t understand the consequences of our actions, maybe that signals a tremendous risk and we should cease until we have a better grasp: do no more harm until we know what we are about. Unfortunately, there’s no money in that idea.

12: Why would evolution have resulted in

a being smart enough to fully grasp this ex-

ceedingly complex reality? Maybe humans

are smart enough to ruin things, but not

smart enough to refrain from the ruining.

Sec. D.6 (p. 408) explores this further.### 19.1.1 The Growth Imperative

Lacking a master plan, the current situation can be described as operating on “autopilot,” guided—rather cleverly and impressively—by market forces. In a world far from environmental limits, this model effectively maximizes growth, development, innovation, and prosperity.13 13: . . . although resources are not typically

Much as it is in the case of fossil fuels, it is hard to fault growth for all the good it has brought to this world. Yet, as with fossil fuels, nature will not allow us to carry the model indefinitely into the future, as was emphasized earlier in this book. Growth must be viewed as a temporary phase,14 emphasizing the need to identify a path beyond the growth phase. Before discussing how this might manifest, the list below illustrates the dominance of growth in our current society.

14: Recall that Chapter 2 made the argu-- 1. If a politician or activist calls your phone during an election cycle, ask if their platform supports growth.15 15: . . . in terms of the economy, jobs, com-Of course it does. It is hard to find mainstream politicians opposed to growth, and this is fundamentally a reflection of attitudes among the populace.

- Communities make plans predicated on growth. Most seek ways to promote growth: more people, more jobs, more housing, more stores, more everything.

- Financial markets certainly want growth. Recessions are the scariest prospect for banks and investors. What would interest rates or investment even mean without growth? What role would banks play?

- Social safety net systems16 16: . . . pensions, retirement investment, soare predicated on growth both in the workforce (as population grows) and the economy (so that interest accumulates). In this way, post-retirement pay can be greater than the cumulative contributions that an individual pays during their career. A retiree today is benefiting not only by accumulated interest on their past contributions to the fund, but on a greater workforce today paying into the fund. If growth falters in either or both (workforce/interest), the institution is at risk. It is essentially a

pended on a pristine sofa for some reason

a being smart enough to fully grasp this exceedingly complex reality? Maybe humans are smart enough to ruin things, but not smart enough to refrain from the ruining. Sec. D.6 (p. 408) explores this further.

well-distributed, leading to inequality

ment that economic growth can’t continue indefinitely.

munity, housing, you name it

cial security, government health care

slow-moving pyramid scheme that cannot be sustained long-term, given limits to growth. It was a neat idea for the growth period, but its time will come to an end.

- Various figures from this text (Fig. 1.2; p. 7, Fig. 3.2; p. 31, Fig. 7.7; p.109, Fig. 8.2; p.118, Fig. 9.1; p.139) show a relentless growth in people and resources—often looking like exponential growth. Growth has been a central feature of our regime for many generations.

In other words, human society is deeply entrenched in a growth-based model for the world. This does not augur well when the finite planet dictates the impossibility of indefinite growth.

19.319.2 No Prospect for a Plan¶

Not only do we lack a plan for how to live within planetary limits, we may not even have the capacity to arrive at a consensus long-term plan. Even within a country, it can be hard to converge on a plan for alternative energy, a different economic model, a conservation plan for natural resources, and possibly even different political structures. These can represent extremely big changes. Political polarization leaves little room for united political action. The powerful and wealthy have little interest in substantial structural changes that may imperil their current status. And given peoples’ reluctance to embrace austerity and take personal responsibility for their actions, it is hard to understand why a politician in a democracy would feel much political pressure17 to make long-term 17: . . . discussed in Sec. 18.2 (p. 309) decisions that may result in short-term hardship—real or perceived.

Globally, the prospects may be even worse: competition between countries stymies collective decision-making. The leaders of a country are charged with optimizing the prosperity of their own country—not that of the whole world, and even less Earth’s ecosystems. If a number of countries did act in the global interest, perhaps by voluntarily reducing their fossil fuel purchases in an effort to reduce global fossil fuel use, it stands to reason that other countries may take advantage of the resulting price drops18 to acquire more fossil fuels than they would 18: . . . from lowered demand have otherwise—defeating the original purpose. Then the participating countries will feel that they self-penalized for no good reason. Unless all relevant nations are on board and execute a plan, it will be hard to succeed at global initiatives. The great human experiment has never before faced this daunting a set of global, inter-related problems (see Box 19.3 for an underwhelming counterpoint). The lack of a global authority to whom countries must answer may make global challenges almost impossible to mitigate. Right now, it is a free-for-all, sort-of like ∼200 kids lacking any adult supervision.

17: ... discussed in Sec. 18.2 (p. 309)

18: ... from lowered demand

19.3.0.1Box 19.3: What About Ozone?¶

Scientists discovered an alarming decrease in stratospheric ozone (O3) in the latter part of the twentieth century—particularly acute aver the Antarctic, earning the title “ozone hole.” A global agreement in 1989 called the Montreal Protocol banned the use of chlorofluorocarbons.19 19: . . . often found in refrigerant fluids and aerosol cans Substitutes largely—but not entirely—mitigated the ozone problem. Ozone depletion has improved by 20% since 2005 [122] [122]: Nunez (2019), "Climate 101: Ozone . While the problem is not yet gone, or solved, it is encouraging that global policy can at least reverse and possibly fix a problem.

On the scale of things, this was an easy problem to solve. Climate change and fossil fuel dependence are much harder, making the ozone comparison a false equivalency. Getting energy out of fossil fuels demands the release of CO2. We can’t “just” switch20 20: An analogy is if your doctor told you to some other liquid fuel that doesn’t have this problem, as this book makes clear.

Problems are not all the same size. Switching to alternate refrigerants was painful, but not so much that countries and industries could not absorb the cost. Asking to abandon primary energy sources is a much bigger ask. Witness the fact that the rate of CO2 emissions grows every year, despite global awareness of the problem.

Many residents of the U.S. also remember great concern over acid rain in the 1970s and 1980s, along with other environmental damages that seem to have been fixed. Part of this is real, and part is illusory. The real part is that coal-fired power plants did adopt technology to scrub sulfur and other trace pollutants out of the emissions stream. This is relatively easy compared to dealing with CO2, which is not a tiny fraction of emissions, but practically all of it.21 The illusory part of reduced acid rain impact on the U.S. environment has to do with moving much of the manufacturing capacity overseas. What happened to environmental quality in Asia as a result? Local solutions are not global ones.

21: It’s one thing to rinse off (scrub) cansWhether trying to bring about change on a national or global level, the associated political decisions are especially fraught if any form of sacrifice is involved. Examples may be reduced travel, less “comfortable” thermostat settings, taxes or other cost structures making energy and resources more expensive, or more responsible diets. Imposing any such hardships may be politically untenable. Yet, if constrained to operate under a condition of no sacrifice in solving our problems, the only viable paths forward may be closed off, thus setting the stage for failure. In an attempt to have everything, we risk winding up with nothing.

19.3.0.2Box 19.4: Paris Agreement and Kyoto Protocol¶

The United Nations is the closest thing to a global government, but in practice only has as much authority as member nations wish it to

19: ...often found in refrigerant fluids and aerosol cans

Depletion"

to avoid monosodium-glutimate (MSG) in your food, you’d be able to find substitutes and still do fine. If your doctor asked you to avoid carbohydrates, protein, and fat sort-of like the three fossil fuels that are the staple of our diet—we’d be down to what, exactly? Progress in eliminating MSG says little about prospects for addressing the much larger problem.

before putting them in the trash. It’s another thing entirely to eliminate the production of trash (CO2) altogether.

have. Occasionally, the U.N. sponsors international pacts to set limits on CO2 emissions in a quest to limit the harm of climate change. The Kyoto Protocol of 1997 and Paris Agreement of 2015 are the most notable of these.

Despite the best of intentions, the agreements have not yet shown effectiveness, in that CO2 rises faster than ever (Fig. 9.1; p.139). Countries fail to meet their target reductions, and suffer no penalties: what authority would enforce the targets, and how? Until people are willing to voluntarily use less and/or pay more for energy, these scientifically solid and well-meaning international agreements will lose out to political pressures for cheap comfort at a national level.

19.3.119.2.1 Who Makes the Plan?¶

So how might a viable plan emerge? Who might produce one? Corporations cannot be expected to lay out a responsible plan for our future. Their interest is in company health and profits.22 In fact, corporations have a fiduciary obligation to their shareholders to maximize profit. Demonstrable failure to do so is technically illegal, and could result in damaging lawsuits.

22: ... usually confined to short-term: quarterly, annual

Governments are in a better position, presumably interested in the longterm health and viability of the country. Many governments, however, are constrained by election cycles that in the U.S. are every 2, 4, or 6 years. Decades-long planning is not natural in such high-turnover23 23: . . . or even the threat of high-turnover systems. Authoritarian governments may be in a better position to effect long-term planning, and even have the ability to impose sacrifice for longer-term goals. Yet, here again the goals are not aimed at achieving global peace and prosperity, but rather securing that particular country’s fortunes and survival.

Similar limitations apply to the military sector. Military bodies do have the luxury to form long-term strategic plans, and can recognize real threats24 to the global order. The only problem is that their charge is to win the day: in the event of a global resource competition, they vie to end up in control, generally through use of force or strategic superiority.

24: The author has been visited by U.S. military strategists concerned about the repercussions of diminishing petroleum supply.

The job of formulating a plan may be best suited to the academic world, as academics have the freedom to pursue research in any direction of their choosing, can spend entire careers focused on the effort, and can afford to think over longer timescales than their own lifetimes. An academic agenda can be global in scope, rather than fighting for the interests of a single corporation or country. As long as an academic is able to demonstrate impact—typically via substantive and original contributions to published literature—they may uphold their end of the tenure pact.25 promises to continue bearing fruit. Ideally, academics of all stripes would gather to formulate a viable future plan for how human civilization might carry forward in a way that respects realities from the realms of physical sciences, engineering,

Author’s note: while this box downplays the impact of international agreements, I still would rather have them than not, in that they do have some impact on emissions and serve as a very public symbolic statement of concern. I’m just not sure they are nearly enough, lacking enforcement and focusing only on climate change: one evident symptom of a much deeper disease about planetary limits and ecosystems. These agreements do not address fundamentals of growth and resource exploitation, and so are band-aids at best. Sometimes band-aids are the appropriate choice for minor wounds, but don’t expect them to cure potentially fatal diseases.

terly, annual

23: . . . or even the threat of high-turnover

itary strategists concerned about the repercussions of diminishing petroleum supply.

25: Contrary to a common misconception, it is rare for tenured professors to rest on their laurels. Tenured professors by-andlarge are intensely driven to push the boundaries of knowledge (which is what earns tenure), and are unlikely to change character upon being granted tenure. In fact, tenure should be looked at not as a reward for past accomplishments, but an investment in a future that (based on past accomplishment) economics, political science, sociology, psychology and cognitive science, history, anthropology, industrial studies, communications, and really all other academic fields. Every field of study has a stake in the fate of human civilization and has meaningful understandings and insights to contribute.

Of course, any such plan that might emerge will be attacked from all sides, derided as alarmist academic fantasy. It is exceedingly difficult to imagine that the entrenched world will just decide to get started rebuilding the world according to “the plan.” But the hope is that if conditions eventually deteriorate to the point that continuation of business as usual is clearly not viable, enough people may remember the plan and dust it off to see what insights it might contain.26 In such a scenario, hopefully it is not too late to salvage a satisfying future. 26: In this sense, we might view such a master plan as a "break glass in case ofA vital group has been left out of the discussion thus far: people. The vast majority of people are not on corporate boards, in positions of government or military power, or in academic roles. Any effective adaptation to a different future plan will need people to be on board, which means educating them on the choices ahead and the consequences of our actions. Broad support will likely be crucial in redesigning our world to gracefully adapt to the realities of planetary limits.

19.3.219.3 Economic Regimes¶

A very nice metaphor presented in the 2003 documentary The Corporation is that early attempts at mechanized flight were doomed to fail because the contraptions were not built on aerodynamic principles of sustainable flight. All the same, the would-be pilots launched off cliff edges and momentarily felt the thrill of flying: the wind was in their hair.Meanwhile, the ground was rushing up. Likewise, our economy and society are not built on principles of sustainable steady-state operation. Even though it feels like quite the amazing rush,27 27: The wind is in our collective hair; this it is not hard to see evidence that the ground rushing up. Our only chance is to develop a steadystate economic model—one that is based on principles of long-term sustainability in partnership with Earth’s ecosystems.

Paying heed to true sustainability is challenging. Firstly, it is difficult to define what it means. Much depends on the lifestyle imagined. The earth can support fewer people if resource consumption per capita is high, for instance.

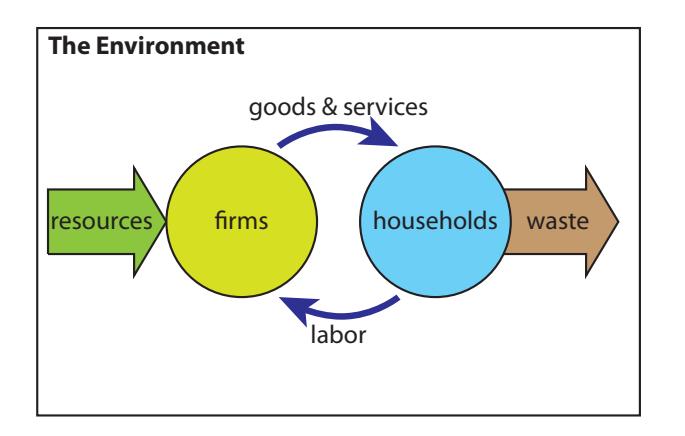

A story illustrates the challenge. An economist named Herman Daly worked at the World Bank in a division focused on the interaction between the economy and the environment. When his division was asked to issue a report on this interaction, an early draft had a standard depiction of the economy showing firms and households (Figure 19.1). Firms supplied goods and services to households, while households

master plan as a “break glass in case of emergency” safeguard.

is fun!

provided labor for the firms. Resources fed the firms and waste was emitted from the households (and firms). Dr. Daly said: "great, now draw a box around this and label it: The Environment. The obvious point is that all economic activity takes place inside the environment. The next draft came back sporting a box drawn around the figure, but no label. Dr. Daly’s response: “It looks nice, but unless the box is labeled The Environment, it’s only a decorative frame.” The next draft eliminated the figure altogether.

Once a box is drawn around the economy, many uncomfortable questions arise: how big should the box be (Figure 19.2)? Are we running out of room? What happens when the box fills up? Economists and governments are not prepared to answer such questions.

A nascent field called Ecological Economics [123], of which Herman Daly is a pioneer, has emerged from deep concerns about interactions between human activity and natural systems. Unlike the more established branch called Environmental Economics, which preserves the basic foundations of neo-classical economics and attempts to put prices28 on environmental factors, ecological economics abandons the growth paradigm and tries to establish rules for maintaining an indefinite relationship with our planet’s resources and natural services.

28: Economics lingo would call this "inter-Herman Daly described the different philosophies by analogy to loading a boat. Macro-economics concerns itself with the overall distribution of products within the boat. It is unwise to load all the cargo into the front or back, or all on one side: much better to uniformly load the boat so that it stays level. In analogy, an economy wants to strike a balance across the wide variety of goods and services offered, so that it is not riddled by giant surpluses in one area and deficits in another. Microeconomics deals with the details of how to efficiently manufacture and sell the contents of each box: materials; supply chains; labor; marketing; distribution. But traditional economics has no concept for how much cargo the boat should hold—much like we have not established the size of the “box” within which the economy operates (as in Figure 19.2).

Figure 19.1: Standard concept of the economy, but importantly surrounded by a finite box labeled “The Environment.” Most instances of this figure avoid the insinuation that the economy is contained in a finite domain, in part because it raises the uncomfortable question of how close we are to filling up the box.

Figure 19.2: Does our economy have ample room, or is it straining the limits of the environment?

nalizing externalities." Typically, the price additions are too minor to be disruptive or fully capture the cost to nature, which is very hard to assess objectively.

In effect, our “boat” has no “waterline” painted on its side to indicate when it is fully loaded. The word “macro” in macro-economics makes it sound like the “big picture” view, but it’s really just intermediate. By analogy, we might say that micro-economics is about understanding all the complex workings within a house or building. Macro-economics concerns itself with the distribution of various building types and functions within a city. Missing is a branch evaluating how many cities can fit on Earth and be supplied by the environment. Ecological Economics attempts to address this shortcoming, which is not important in an “empty” earth but becomes crucial as the human scale begins to dominate the planet.

19.3.319.3.1 Steady State Economy¶

Chapter 2 demonstrated that economic growth cannot go on forever. Continuing to operate as if growth can—and should—persist risks irrevocable damage to that from which all value ultimately depends and derives: a healthy natural environment. The sooner we can jump ship to a new economic model that can survive the long haul, the better.

A few key principles will help flesh out aspects of how a steady state economy might work. A critical goal is to reduce the flow (or demand) of resources into the economy, and reduce the waste (pollution, CO2, for instance) back into the environment. This would be akin to diminishing the sizes of the two thick arrows in Figure 19.1. One approach would be to levy substantial taxes on every tree that is cut, mineral that is mined, drop of oil that is extracted, or wild animal that is unnaturally removed from the environment. Likewise, a heavy tax would accompany disposal of waste and emissions of pollutants. Meanwhile, labor would no longer be taxed. Labor can add value to resources already in hand. The idea is to tax the damaging things, not the beneficial things.

Think about what happens under these conditions. Buying a newly manufactured item becomes expensive. Throwing away an old device becomes expensive. Repair (labor) becomes cheaper. Say goodbye to the disposable economy, or “planned obsolescence.” Durable goods and lifetime warranties become popular. Items are designed to facilitate upgrade or repair. For instance, once you own a large display at high resolution, good contrast, and good color representation, it should satisfy for a lifetime.29 29: Functional upgrades could potentially Human visual acuity is static, and modern displays are effectively perfect, relative to our biological hardware. If a small electronic component fails, the environmental cost of manufacturing a whole new unit and disposing of the old one is enormous—especially compared to the environmental cost of replacing the small failed component. At present, repair cost often exceeds the cost of replacement and disposal.30 Under the new arrangement, we begin to place greater value 30: . . . disposal is essentially free now in craftsmanship, community resources, and high-quality goods.31 31: . . . less plastic junk!

be modularized to small inserts.

30: ... disposal is essentially free now 31: ... less plastic junk!

Consider now the effect on our consumer treadmill.32 Let’s say you find the perfect toothbrush. When it is worn out, you try to get the same one again. But the company has changed its style, so the one you like is no longer available. Why does this happen? The company has a standing army of designers and marketers that must continually “improve” the product to stay competitive in the market. If we all bought less stuff, or more durable items that lasted far longer, the demand for manufacturing would wane. Markets and politicians shudder to contemplate this, as the result would be recession and loss of jobs.

But a widespread cessation of constant disposal and replacement of low-quality goods would mean that not as much income would be required to satisfy basic needs and to enjoy a quality life. Maybe all those jobs are not really necessary. Maybe a lot of what presently occupies society is a bunch of wasted effort in service of growth33 and not serving 33: Is growth our master? ourselves or the planet well in the process. What if it only takes 10 hours of work per week to live comfortably, having reduced the flow and expense of low-quality stuff once planned obsolescence is—rather poetically—rendered obsolete? Perhaps we could spend more of our time enjoying life, community, family, friends, the natural world, while still retaining scientific literacy and basic technology standards.

It seems that humanity got stuck in a frenetic lifestyle because money and an unrealistic vision of our future trajectory told us to do so.34 34: Ask yourself: to what end? Maybe we need to rethink what we want life to be about, and not simply accept that productivity and profit are the drivers that matter. Are we the boss of money, or is money the boss of us?

Careful thought [124, 125] has been put into how to modify the present financial system toward a steady state. The process has been compared to converting an airplane, which must keep moving forward in order to stay up—as the current economy must grow to survive—into a helicopter that can remain stationary. And this transformation would ideally happen mid-flight. It’s a difficult prospect. Moreover, none of the necessary steps would ever spontaneously happen without the population first embracing the ultimate goal of a steady-state economy. Therefore, a collective push to abandon our current economic model must initiate the process, and it is unclear how this ground swell might materialize.It is possible that a steady-state economic framework—for all its merits and careful thought—is ultimately naïve and infeasible. Individuals may be naturally driven to work very hard to build an empire and improve their own lot. It is not obvious that human nature is suited to a steady state existence: competition and acquisition of power may be built in.35 35: . . . as a product of evolutionary pressures Imposing rules to prevent outsized accumulation of wealth or power may seem oppressive and would be hard to sustain, unless societal values uniformly shunned excessive wealth, power, and consumption. But for how many generations could such a state of affairs be maintained? It seems like an unstable scenario.

stop consuming and disposing, even if it’s somewhat pointless. See the Story of Stuff video.

33: Is growth our master?

34: Ask yourself: to what end?

Economy" [125]: Chang (2010), Moving Toward a Steady State Economy

35: ...as a product of evolutionary pres- sures

19.419.4 Upshot on the Plan¶

Humanity has historically not needed a master plan. Plenty of space, resources, and natural services allowed unwitting expansion. Yes, wars occasionally broke out over contested resources, but generally in localized regions. This state of affairs will continue to be true until it isn’t any more. That is to say, just because something has never happened before does not mean it cannot. Earth has never hosted 8 billion high-demand humans, yet here we are. Human imagination is not the ultimate limit in this physical world. At this juncture, it would be prudent to heed the warning signs and attempt to make a plan for survival/prosperity.

Currently, it is hard to imagine any global consensus arising around a plan. Even if able to maintain the current level of global resource demand,36 those who use resources at a much higher rate than average37 may have to scale back as the world equilibrates, and this will not easily be agreed upon. Academic circles may be the only place from which a credible plan might emerge,38 but any such plan would likely be ridiculed and discarded as impractical.

36: It is not at all clear that we c

37: Ahem, America.

38: Who else would pay for it?The silver lining is that some folks have thought about alternative ways to structure the economy allowing abandonment of growth and living within ecological limits. Some of the elements of this plan are very appealing. Only if embraced on a large scale would it be feasible to migrate in this direction, and it is unclear what circumstances might bring about such an attitude change, if it is possible at all.

19.519.5 Problems¶

- To visualize the scale of the $100 trillion global economy relative to the value of the earth—conservatively one million times larger let’s think in terms of animal volume. Volume scales like the cube of linear dimension. How much would you have to shrink a dog in linear scale for its volume to be one-millionth its original size? If the typical scale of a dog is 0.5 m, how large is the shrunken version, and what animal is about this size?

- Subjectively, how much more do you think a planet teeming with biodiversity is worth compared to a comparable planet harboring no life at all? Express as a factor: 1.2 times as much, 2 times as much, 10 times as much, 100, 1 million etc.

- 36: It is not at all clear that we could.

- 37: Ahem, America.

The value likely goes up if your own biology is adapted to that same life-filled planet: it becomes special to you as almost a part of you.

- What institutions can you think of that are prevalent now but will be rendered obsolete—or at least radically diminished—if the economy stopped growing permanently?

- Why do you think we have not yet formulated a master plan for how humans can live on the earth indefinitely without exceeding limits?

- Do you see a route to global acceptance of a plan? What would it take to get there? Would we first need a global government having authority over all nations?

- What is your major in college, and what insights or contributions do you imagine may be offered by this field of study in formulating a workable plan for the future of human life on this planet?

- Presently, the American tendency is to buy a missing tool for a job that may not be needed again for a very long time, if at all. It is likely that some nearby neighbor already has the same tool collecting dust. What do you imagine would be advantages and disadvantages of pooling resources in a lending arrangement?

- Why do you think the field of traditional economics does not recognize limits to growth, and does not have a macro-macro branch looking at the whole planet and its finite nature?

- A central question in mapping a comfortable future has to do with how large our economy is with respect to physical boundaries.39 39: It is even possible we have exceeded One solution would be to set aside some fraction of the planet (land and ocean) off limits to human extraction of any plants, animals, or other resources. What fraction seems tolerable to you? If it turns out that half needs to be protected to guarantee long-term survival, do you think that’s possible/practical? How many generations do you think could maintain the discipline to preserve that rich world in a pristine state?

- What do you find appealing about a steady-state economic model? What do you find worrisome?

- Do you think that human nature—the desire to improve one’s lot and expand empire—is compatible with a steady state economic model? Can you see a way that it might work?

- Are you left thinking that we are likely to establish and implement a viable global plan for how humans might live prosperously on the planet indefinitely, or do you think it is more likely we will fail to do so and “wing it” into whatever fate awaits?

those steady-state bounds and are spending down an irreplaceable inheritance right now.