B.1Chemistry Primer/Refresher¶

This book does not rely heavily on past knowledge of chemistry, but it is helpful to know a few basic elements that play a role in fossil fuels, biological energy, and climate change. This section could act as a refresher, or a first exposure to the fundamentals.

B.1.1B.1 Moles¶

Chemistry deals with atoms and molecules and the interactions between them. Atoms and molecules1 are irreducible nuggets of a substance—the minimum unit that carries the essential properties of that substance. Water, for instance, is comprised of two hydrogen atoms bonded to a single oxygen atom, which we denote as H2O.

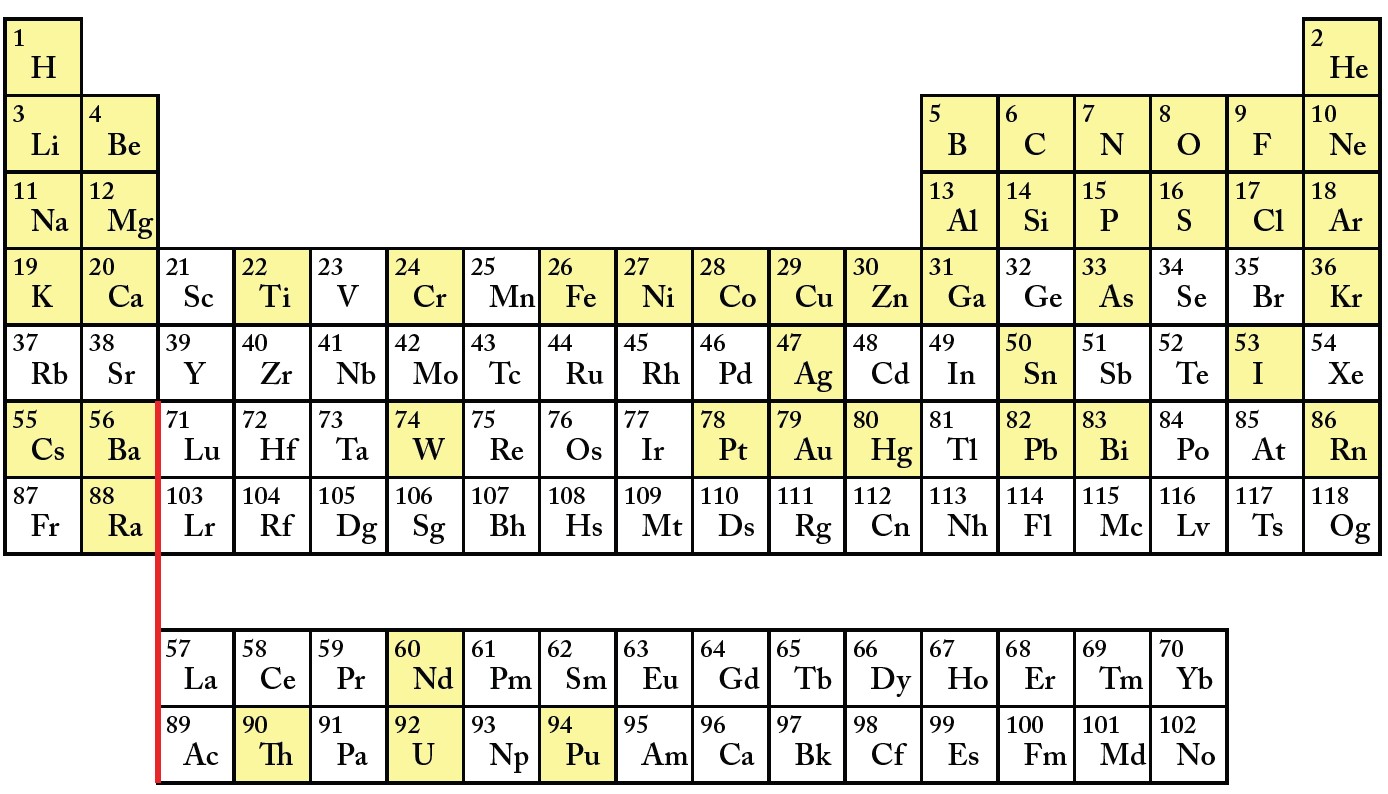

Figure B.1 presents a stripped-down version of the periodic table. Additional exploration of more fully-featured versions is encouraged.[2]

It is natural to imagine that a first step in dealing with piles of atoms and/or molecules is being able to count them. But since individual atoms are fantastically small, the numbers can be overwhelmingly large. This is where the mole3 3: . . . the word molecule begins with mole. comes in. A mole is just a number, and that number is called Avogadro’s number, having a value of 푁A = 6.022 × 1023, or 602,214,076,000,000,000,000,000, if written out.4

The way the mole is defined, essentially, is that 12.000000 grams of neutral carbon atoms (of the isotope having 6 protons and 6 neutrons in its nucleus) will constitute one mole of atoms. In this way, the masses of lighted elements would be worthwhile.

3: ...the word molecule begins with mole.

4: Unfortunately, it can be hard to remember if it is supposed to be or . For this reason, it may be wise to forget about the 22 and just remember , or even as something that is very slightly wrong but much better than being 10 times off!

1: Molecules are made from a handful of atoms.

other elements—being comprised of an integer number of protons and neutrons5—will tend to be close to an integer number of grams. 5 For instance, a mole of hydrogen atoms is very close to 1.00 grams. A mole of helium is very nearly 4.00 grams, nitrogen 14, oxygen 16, etc. 5 ...and associated light-weight equal in number to the protons 6So the concept of the mole is pretty straightforward: just a number albeit a very large one.

B.1.1.1Box B.1: Moles to Mass¶

Incidentally, the inverse of Avogadro’s number becomes the definition of the atomic mass unit (a.m.u.). The a.m.u. can be thought of as the average mass of an atom per nucleon. 7 In other words, carbon-12 (6 protons, 6 neutrons) has a mass of 12 a.m.u. In fact, this is how the a.m.u. is defined. This means that hydrogen (a single proton) has a mass very close to 1.00 a.m.u., and oxygen-16 (8 protons, 8 neutrons) has a mass close to 16.00 a.m.u. Chapter 15 delves into the subtle reason why these are not exactly 1.00000 and 16.00000 in these cases.Since one mole of 12.00000 a.m.u. carbon-12 atoms is defined to have a mass of 12.00000 g, one mole of 1.000000 a.m.u. particles8 would have a mass of 1.000000 g. Therefore, a single 1.000000 a.m.u. particle would have a mass of 1.000000 g divided by Avogadro’s number, , which turns out to be g, or kg. This is the number you will find if looking up the atomic mass unit (also called a Dalton).## B.2 Stoichiometry

Chemistry starts by counting atoms and molecules. Since molecules are comprised of integer numbers of atoms of specific types, the counting fun does not stop there. When atoms and molecules react chemically, the atoms themselves are never created or destroyed—only rearranged. This means that an accurate count of how many of each atom type are present at the start, a proper count at the end should yield exactly the same results.

Before we get into balancing chemical reactions, we need to know something about the scheme for labeling chemical compounds. A compound is an arrangement of atoms (representing pure elements) into a molecule. For instance, water is made of three atoms drawn from two elements: hydrogen and oxygen. Two atoms of hydrogen are bonded to an atom of oxygen to make a molecule of water. We denote this as H2O.

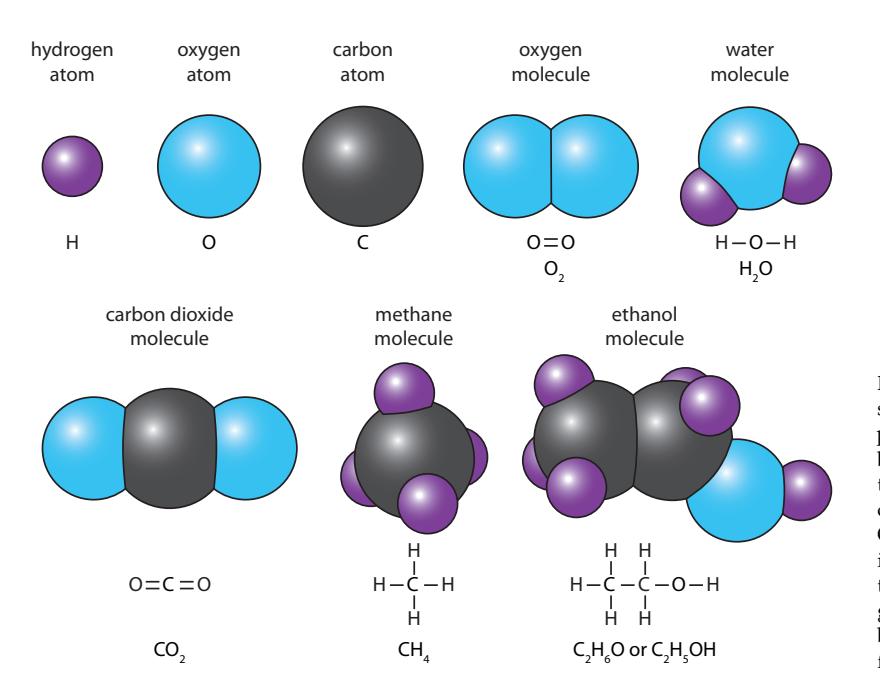

Examples of a few familiar atoms and molecules are presented in Figure B.2. Each one is named at the top. Below each one appears the bond structure in the case of molecules and the chemical “formula” in all cases. Notice that hydrogen atoms always have a single bond (single 5: . . . and associated light-weight electrons

6: Blends of different isotopes can mess up this convenient arrangement in natural (mixed) samples, however.

7: A nucleon is either a proton or a neutron: the two types of particles that occupy the nucleus of an atom and are responsible for almost all of the atom’s mass.

8: . . . if such a thing were to be found/created

Figure B.2: Representing atoms as colored spheres for schematic purposes, we can depict the general appearance of molecules as bonded collections of atoms. Here, we have three elements—hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon—combined into familiar molecules. Oxygen in the air we breathe is self-bonded into a “diatomic” molecule. Two representations appear below each molecule: a diagram indicating bonds (including doublebonds in some cases), and the chemical formula.

electron to share), oxygen has two (wants to “borrow” two electrons to feel good about itself), and carbon tends to have four (either donating four in the case of CO2, or accepting four when bonding to hydrogen). The chemical formula for each uses elemental symbols to denote the participants and subscripts to count how many are present.

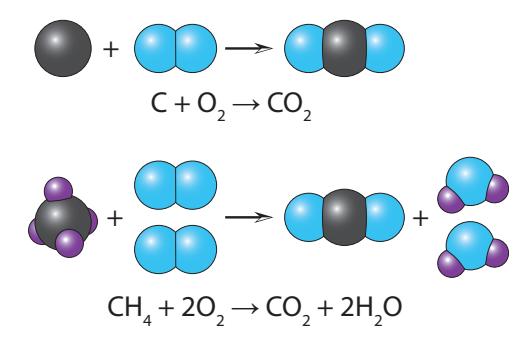

Now we come to a bedrock practice in chemistry called stoichiometry which boils down to counting atoms in a reaction to make sure no atoms are missing or spontaneously appear. To get a sense of this, see Figure B.3 for two examples. The graphical version captures the physical reality, so that simply counting the number of spheres of each color on the left and right had better match. Below each graphical reaction is the associated chemical formula. Each formula contains an arrow indicating the direction of the reaction (separating “before” and “after”). Numerical factors (coefficients, or prefactors) in front of a molecule indicate how many molecules are present in the reaction. To get the total number of atoms represented, we must multiply the subscript for that atom (implicitly 1 if not present) by the prefactor.10 10: For example, 2H2O has a total of 4 hy-

Example B.2.1 Let’s figure out a tougher formula, pertaining to the combustion of ethanol (depicted in Figure B.2.). In this situation, we combine a C2H6O molecule with some number of oxygen molecules (O2), and the reaction products will be CO2 and H2O (carbon dioxide and water). Our job is to figure out how many molecules are needed to balance the reaction:

9 9: Two variants are shown for ethanol. The first is a no-nonsense census of the atoms, while the second pulls one of the H symbols to the end to call attention to the OH (hydroxyl) tagged onto the end of the molecule. In either case, the formula specifies 2 carbons, 6 hydrogens, and 1 oxygen, in total.

drogen atoms and 2 oxygens.

where question marks indicate what we need to figure out. Three unknowns and one equation? It may seem hopeless, but the formula is not the equation. The equations are that the total number of carbons on each side are equal, the total number of oxygens are equal, and the total number of hydrogens are equal. So we actually have three equations.11 11: Equations are just statements of truth

Start by noticing that the left side has 2 carbons and 6 hydrogens. We don’t know how many oxygens yet, but it’s good enough to start. On the right, carbon only shows up in CO2, so getting 2 carbons on the right requires 2CO2. Likewise, hydrogen only shows up in water, and ethanol has 6 hydrogen atoms to stuff into water molecules that hold 2 hydrogens apiece. It will obviously take 3 water molecules to account for 6 hydrogens.12 So now the right side is hammered out:

The only thing left to figure out is how many oxygens are on the left. To balance the reaction, count the number of oxygen atoms on the right. Four come from the two CO2 molecules, and 3 from the water for a total of 7. One oxygen was already present in the ethanol molecule on the left, so only need 6 in the form of O2, thus requiring three of these:

The job is done: the reaction is now balanced. That’s stoichiometry.

The treatment above cast chemical reactions at the most fundamental level of individual molecules reacting. In practice, reactions involve great numbers of interacting particles, so it is often more convenient to think in moles. In fact, common practice is to look at the prefactors13 in chemical reaction formulas as specifying the number of moles rather than the number of individual molecules. Either way, the formula looks exactly the same,14 and it’s just a matter of interpretation.Thinking of the chemical formulas in terms of moles makes assessment of the masses involved more intuitive. Recall that one mole of carbon Figure B.3: Two example fossil fuel reactions (combustion) are shown here. The first is coal and the second is natural gas (methane). Both cases simply rearrange the input atoms without creating or destroying any, so that the count is the same on both sides of the arrow (which denotes the direction of the reaction). In other words, four purple hydrogens on the left in the case of methane must all appear on the right somewhere. The formula version also just counts instances of each atom/molecule, in which pre-factors (coefficients) indicate how many molecules are present.

that we can create on our own. They are just a way to express what we know about a problem.

number of hydrogens on the left? We’d need to double the number of hydrogencontaining molecules on the left to produce an even number and start over.

13: ... also called coefficients

14: To be explicit, if a formula is balanced for individual molecules, then it should also be balanced if doubling the “recipe,” or tripling, multiplying by 10, or even by 6 × 10 .atoms is exactly 12 grams, that hydrogen is 1 g, and oxygen is 16 g. That means one mole of water molecules (H2O) will be 18 g (16 + 1 + 1), one mole of carbon dioxide (CO2) is 44 g (12 + 16 + 16), and one mole of ethanol (C2H6O) is 46 g (12 + 12 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 16). We refer to this figure as the molar mass, and standard periodic tables display the molar masses for each element: the mass of one mole of the substance. The unit is typically grams per mole, or g/mol.Example B.2.2 How much mass of CO2 will emerge from the burning of 1 kg of ethanol? We start with the formula we worked out in Example B.2.1:

This problem can be approached in Two equivalent ways: either figure out how many moles of ethanol it takes to amount to 1 kg and then scale the formula accordingly; or just work it out for one mole to get a ratio and then apply to 1 kg. We’ll do it both ways.

Since ethanol has a molar mass of 46 g, one kilogram corresponds to 21.7 moles. So we could re-write the formula as:

where we have multiplied each prefactor (coefficient) by 21.7. CO2 has a molar mass of 44 g/mol, so 43.5 moles will come to 1.91 kg.

The other approach is to note that 2 moles of CO2 are produced for every one mole of ethanol combusted. So 88 g of CO2 (44 g/mol) results for every 46 g of ethanol supplied. This ratio is 1.91. So 1 kg of ethanol input will make 1.91 kg of CO2 out, as before.

B.2B.3 Chemical Energy¶

Atoms (elements) can bond together to make molecules (compounds). The bond—formed by outer electrons within the atoms—can be strong or weak. It takes energy15 to pull apart bonded atoms. It stands to reason that when two atoms form a new bond, energy is released—usually as vibrations that we know as heat. In a typical reaction, some bonds are broken and other new ones formed. If the balance is that the new bonds are stronger than the broken bonds, energy will be released. Otherwise, energy will have to be put into the reaction to allow it to happen.

15: Recall that energy is a measure of work, or a force times a distance.In the context of this book, chemical energy is typically associated with combustion (burning) a substance in the presence of oxygen. This is true for burning coal, oil, gas, biofuels, and firewood. In a chemistry class, one learns to look up the energetic properties of various compounds in tables, combining them according to the stoichiometric reaction formula

or a force times a distance.

to ascertain a net energy value. We’re going to take a shortcut to all that, by introducing the following approximate formula for combustion energy. This empirical formula can serve as a gen-

The approximate energy available from the compound CcHhOoNn—where the subscripts represent the number of each atom in the molecule to be burned—is:

(B.1)

For instance, sucrose has the formula C12H22O11, so that , , , and . The denominator in the formula is just the molar mass,16 or 342 in this case. The numerator adds to 13.1, so that the result is 3.8 kcal/g—very close to the expected value around 4 kcal/g for a carbohydrate like sugar.The numerator of Eq. B.1 tells us that we get the most energy from each carbon atom, 30% as much from each hydrogen atom, and take a 50% hit (deduction) for each oxygen atom. Nitrogen is energetically inert and does not contribute to the numerator—while degrading the energy density by adding mass in the denominator. The negative coefficient for oxygen tells us something important. Since combustion is a process of joining oxygen to atoms in the fuel, the presence of oxygen already in the fuel means it is already partly “reacted” and has less to offer in the way of new oxygen bonds.

We can explore the sensibility of Eq. B.1 by testing it on some known boundary cases.17 Since one ubiquitous end-product of combustion is CO2, calculating for CO2 should offer no energy to us, since it’s a “waste” product at the end of the energy process. H2O, as another common combustion product, is likewise effectively neutralized in the formula (the result is at least made to be very small). Table B.1 provides some examples of what Eq. B.1 delivers for familiar carbon-based substances. Note that oxygen content (last column) drives energy down, while hydrogen offers a boost.

build trust and competence using the tool before applying it more broadly.

Try it out, using and .

Try this one, too, coming up wi your own values for h and o.

| substance | formula | Eq. B.1 kcal/g | true kcal/g | % C | % H | % O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glucose | C6H12O6 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 40 | 7 | 53 |

| typ. protein | C5H10O3N2 | 4.4 | ~4 | 41 | 7 | 52 |

| coal | C | 8.3 | 7.8 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| typ. fat | C58H112O6 | 9.8 | ~9 | 77 | 12 | 11 |

| octane | C8H18 | 11.8 | 11.5 | 84 | 16 | 0 |

| methane | CH4 | 13.8 | 13.3 | 75 | 25 | 0 |

The resulting calculated energies are definitely in the right (expected) ranges. Notice that the “winners” have little or no oxygen as a percentage of the total molecular mass. The lower-energy entries in Table B.1 are more than half oxygen, by mass.

eral guide, but should not be taken as a literal truth from some profound derivation. It captures the main energy features and produces a useful, approximate result.

flect the fact that carbon is 12 units of mass, oxygen is 16, etc.

17: This is a generically useful practice: it helps integrate new knowledge into your brain by validating the behavior in known contexts. Does it make sense? Can you accept it, or does it seem wrong/suspect? Experts often apply new tools first to familiar situations whose answers are known to build trust and competence using the new

Try it out, using 푐 = 1 and 표 = 2.

Try this one, too, coming up with your own values for ℎ and 표.

Table B.1: Example approximate chemical energies. The results of the approximate formula are compared to true values (favorably). Fractional mass in carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen also appear—emphasizing the penalty for molecules already carrying oxygen.

B.2.0.1B.4 Ideal Gas Law¶

Another topic covered in chemistry classes that strongly overlaps physics is the ideal gas law. This relationship describes the interactions between pressure, volume and temperature of a gas. In chemistry class, it is learned as

where stands for pressure (in Pascals18), is volume (cubic meters), is the number of moles, is temperature (in Kelvin), and is called the gas constant, having the value

18: A Pascal (Pa) is also a Newton of force

(B.3)

To get degrees in Kelvin, add 273.15 (273 among friends) to the temperature in Celsius.19 Standard atmospheric pressure is about 105 Pa.20

Example B.4.1 Let’s say we have a gas at “standard temperature and pressure” (STP), meaning 0 ° C (273 K) and Pa. How much volume would one mole of gas21 occupy?We have everything we need to solve for volume, so

Okay; lots going on here. After the three values in the numerator are multiplied, the only surviving unit is J (Joules of energy). The unit in the denominator is Pascals, but this is equivalent to Joules per cubic meter. So the answer emerges in cubic meters, as a volume should. Since a cubic meter is 1,000 liters, we find that a mole of gas at STP occupies 22.4 L—a number memorized by many a chemistry student!

Physicists prefer a variant of the ideal gas law that derives from the study of “statistical mechanics,” which is practically synonymous with thermodynamics and relates to the study of interactions between large ensembles of particles. The form looks pretty familiar, still:

(B.4)

Pressure, volume, and temperature are all unchanged, and expressed in the same units as before. Now, 푁 describes the number of particles (quite large, usually), and 푘B is called the Boltzmann constant, having a value

Notice that , the number of particles, and , the number of moles, differs simply by a factor of Avogadro’s number, . Indeed, if we multiply by , we get 8.314, and are back to .22per square meter, which reduces to more fundamental units of J/m3 (Joules of energy per cubic meter).

19: And 20: 1 atmosphere is 101,325 Pa.

law does not care what element or molecule we are considering!

22: The units work, too, since 푁A effectively

has units of a number (of particles) per mole.Example B.4.2 Gas is stored at high pressure at room temperature in a metal cylinder, at a pressure of about 200 atmospheres.23 23: . . . means 200 times atmospheric pres-The cylinder is designed to meet a safety factor of 2, meaning that it likely will not fail until pressure reaches 400 atmospheres. If a fire breaks out and the cylinder heats up, the pressure will rise. How hot must the gas get before the cylinder may no longer be able to hold the pressure (assuming no fire damage to the cylinder itself)?

We could start throwing numbers into the ideal gas law, but we don’t know the volume or number of moles (or particles). Heck, we’re not even given a temperature. Ack! Students hate this sort of problem, because it does not appear to be algorithmic in nature. No plug and chug (an activity that does not engage the brain heavily, and thus its appeal).

But we’re okay. What is room temperature? Something like 20–25◦C, so that’s 293–298 K. Whatever the volume is, or the amount of gas in the cylinder, those things don’t change as the temperature rises.24 24: The gas is not leaking out, and the cylinder does not change size—at least not What we’re left with is a straightforward scaling between temperature significantly—as it warms. and pressure (because the numerical factors are all constant for our problem). Therefore, if temperature doubles, pressure doubles.25 25: That’s one of the things Eq. B.4 is trying

Hey, it’s doubling pressure that we are interested in, which will happen if the temperature doubles. So if the temperature goes up to about 600 K, we may be in trouble. It is easy to imagine that a fire could create such conditions. Notice that we are not bothering to say 586–596 K, but just said about 600 K. Do you want a precise temperature when the thing will rupture? Good luck. The point at which it explodes may be 405 atmospheres or it may hold on until 453. Also, how likely is it that all the gas throughout the cylinder is at exactly the same temperature when being heated by a nearby fire? So let’s give ourselves a break and not pretend we’re totally dialed in. There’s a fire, after all.

sure

This is an example where internalizing the ideal gas law for what it means, or what it says is more important than treating it like a recipe for cranking out problems. Don’t just treat equations as mechanical objects: learn what it is they have to say!

24: The gas is not leaking out, and the cylinder does not change size—at least not significantly—as it warms.

to say, beneath all the bluster.

Perhaps at least identifying the high-