A.1Math and Equations¶

Depending on background, math and equations may be an intimidating “foreign language” to some students. This brief appendix aims to offer a refresher on techniques, and hopefully inspire a more peaceful relationship for students.

A.2A.1 Relax on the Decimals¶

First, we can form a more natural, forgiving relationship with numbers. Like your friends, they need not be held to exacting standards: they are simply trying to tell you something useful. Remembering that 휋 is roughly 3 is far more important than committing any further decimals to memory. If a friend traced out a circle in the sand and asked how much area it had,1 the poorly-defined and irregular boundary defies precise 1: Now that’s a quality friend! measurement, so why carry extra digits. Maybe just recognize that the radius is roughly one meter, so the area is about 3 square meters. Done.2 The message here is to give yourself a break and just not over-represent the precision (number of decimals) in your answer.

Part of the reason students have a rigid relationship with numbers is because Some classes formalize the concept of sighomework and test problems tend to come pre-loaded with numbers assumed to be exactly known. But the real world is seldom so generous, leaving us to forage for approximate numbers and estimations.

By being approximate in our use of numbers, we are liberated to do math in our heads more readily. Practice can make this into a life-long skill that becomes second nature. It is helpful to know some shortcuts.

Example A.1.1 To explore the flavor of approximate math, let’s consider the statement:

Your calculator will disagree, but that’s why we use the ∼ symbol (similar) instead of = (equal). Another common option is ≈ (approximately). Your calculator is not as clever as you, and can’t appreciate when things are close. It’s pedantic. Literal. You can be better.How do we use this loose association? We saw one example of using 휋 ∼ 3 before, so will not repeat here.

1: Now that’s a quality friend!

2: Also notice that the circle fits within a square 2 meters on a side, so the area should be less than 4 m2 : it hangs together.nificant digits, which is all well and good. But such systems can add to the stress of students learning the material (one more thing that can be wrong!).

What about ? This implies that , which is true enough (because 9 and 10 are very close; only 10% different). This means if you pay me $30 per day for a month, I know immediately that’s about $1,000. Is the month 30 days, or 31? Who cares? Knowing I’ll have an extra ~$1,000 is a good enough basis to make reasonable plans, so it’s very useful, if not precise.

3: Really .How about ~ 3?4 This one is actually pretty similar to saying that ~ 3, since both imply 3 × 3 ~ 10. To use another example, let’s say you land a $100,000/yr job, but can only work for 4 months (a third of a year).5 If ~ 3, then you’d expect to get about $30,000. Why mess around being more precise? Taxes will be larger than the imprecision anyway. Again, it’s good enough to have a sense, and make plans. 4: Really it’s about 3.333. 5: Money examples often seem easier to mentally grasp because we deal with money all the time. To the extent that money exam- ples are easier, it says that the math itselfMuch like we have multiplication tables stamped into our heads, it is often very useful to have a few reciprocals floating around to help us do quick mental math. Some examples are given in Table A.1 that multiply to 10. Students are encouraged to add more examples to the table, filling in the gaps with their favorite numbers.

The values in Table A.1 are selected to multiply to 10, which is an arbitrary but convenient choice. This lets us “wrap around” the table and continue past three down to 2.5, 2, etc. and learn that the entry for 1.5 would be 6.67. To make effective use of the table, forget where the decimal point is located! Think of the reciprocal of 8 as being “1.25–like,” meaning it might be 0.125, 12.5, or some other cousin. The essential feature is 125. Likewise, the reciprocal of 2.5 is going to start with a 4.

Example A.1.2 How is Table A.1 useful to us? We can turn division problems, which tend to be mentally challenging, into more intuitive multiplication problems. Several examples may highlight their usefulness.

What is one eighth of 1,000? Rather than carry out division, just multiply 1,000 by the reciprocal—a “125–like” number. In this case, the answer is 125. We can use common sense and intuition to reject 1,250 as of 1,000, as we know the answer should be significantly smaller than 1,000. But 12.5 goes too far. Also, we can recognize that is not too far from one-tenth,6 one-tenth of 1,000 would be 100, close to 125.How many hours is one minute? Now we are looking for one-sixtieth of an hour, so we pull out the “167–like” reciprocal and weigh the choices 0.167, 0.0167, 0.00167, etc. Well, can’t be too far from , which would be 0.01. We expect the result to be a little bigger than , leaving us to have one minute as 0.0167 of an hour.Now we do a few quick statements that may not match our table exactly for all cases, but you should be able to “read between the lines” using blurry numbers to reconcile the statements. One out of seven

3: Really √

mentally grasp because we deal with money all the time. To the extent that money examples are easier, it says that the math itself isn’t hard: the unfamiliar context is often what trips students up.

Table A.1: Reciprocals, multiplying to 10.

| Number | Reciprocal |

|---|---|

| 8 | 1.25 |

| 6.67 | 1.5 |

| 6 | 1.67 |

| 5 | 2 |

| 4 | 2.5 |

| 3 | ~3 |

6: This is where “blurry” numbers are useful: 8 ∼ 10 if you squint.

Study Table A.1 for each of these statements to see how it might fit in.

Americans is roughly 15%. A month is about 8% (0.08) of a year. Six goes into 100 a little more than 16 times. Four quarters make up a dollar. 휋 fits into 10 about 휋 times. Each student in a 30-student class represents about 3% of the class population.

Some students view math and numbers as dangerous, unwelcoming territory—maybe like deep water in which they might drown. But think about dolphins, who not only are not afraid to immerse themselves in deep water (numbers), but frolic and play on its surface. Numbers can be that way too: flinging them this way and that to see that a calculation makes sense in lots of different ways. Humans are not natural-born swimmers, but we can learn to be comfortable in water. Likewise, we can learn to be quantitatively comfortable and even have fun messing around. So get your floaties on and jump in!

A.3A.2 Forget the Rules¶

Math, in some ways, is just an expression of truth—a logic about relationships between numbers and their manipulations. It is easy to be overwhelmed by all the rules taught to us in math classes through the years, and students7 can lose sight of the simple and verifiable logic 7: . . . teachers, too! underneath it all. Most math mistakes come from faulty or deteriorating memorization. The good news is that we can usually do simple tests to make sure we’re getting it right. The lesson is not to memorize math! Math makes logical sense, and we can create the right rules by understanding a few core concepts. This section attempts to teach this skill.

Consider for a moment the concept of language (and see Box A.1 for fun examples). Language is riddled with rules of grammar and spelling, yet we learn to speak without needing to know what adjectives or prepositions are. We learn the rules later, after speaking is second-nature. And unlike math, the rules of language can defy logic and have many exceptions. In this sense, math is much easier and more natural. It is the language of the universe. We would likely share no words in common with an alien species8 , but we can be sure that we would agree on the integers, how they add and multiply, all the way up through calculus and other advanced mathematical concepts. We can use its innate nature to expose the rules for ourselves.

A.3.1Box A.1: Rules of Language¶

Let’s step aside for a moment to explore how rules of language are obvious to us without explicit thought.9 Consider the following constructions: trlaqtoef; flort; aoipw; squeet; yparumd. None of these are English words, but only two of them are even worthy of consideration as viable words. The others violate “unspoken” rules

7: ...teachers, too!

8: Except, perhaps we would learn that we inexplicably share the word “sock.”

9: . . . acknowledging that this exercise may be less intuitively obvious to non-native English speakers

about how letters might be arranged in relation to each other. We recognize the nonsense without being able to cite specific rules. Math can work the same way: we can rely on intuition to rule out nonsense.

How about this collection of four words: that, how, happen, did. Now arrange them into a single sentence, ignoring punctuation. Notwithstanding how Yoda might arrange things, only one of the 24 possible arrangements10 makes a single valid sentence. Have you intuited what it is? How did that happen? Without conscious thought, you understand the underlying rules of grammar well enough to see the answer without having to sift through all the combinations. Math can work like that, too.

A.4A.3 Areas and Volumes¶

This book, and the problems within, often assume facility in computing areas or volumes of some basic shapes. Students who have focused on memorizing formulas may see a jumble of 휋, 푟 to various powers, and some hard-to-remember numerical coefficients. For circles and spheres, how do we bring order to the mess?

A helpful trick is to turn the circle into a square, or the sphere into a cube, where our footing is more secure. Hopefully it is clear that the perimeter (length around) of a square whose side length is will be . The area will be . Units can help us, too: if m, then the perimeter should also be a length with units of meters and the area should be in square meters. It would never do to have something like describe a perimeter (wrong units) or to have the area not contain something like . The cube version has volume .About those circles and spheres: The task is to fit a circle or sphere inside of a square or cube, so that . In other words, the diameter ( , where is radius) fits neatly across the side length of the square. The perimeter of the circle should be smaller than the perimeter of the square,11, but a good deal larger than , which would represent a round trip directly across the square, through its center.12 So the circle perimeter is between and , probably not far from . Since , the perimeter should be somewhat close to . Suspecting that shows up somewhere, the leap is not far to the perimeter being . 11: ... literally cutting corners 12: This path would look like a line across the square, traversed twice as a there-and-back trip.Likewise for the area: a circle within the square has an area smaller than that of the surrounding square ( ), but surely larger than half the square area—maybe around three-quarters. In terms of radius, the whole square has area , and three-quarters of this is . Correct again!Volume is a little harder to visualize, but again the sphere will have a volume smaller than that of the cube: . Maybe the sphere’s10: The number of combinations is 4! (fourfactorial), or 4 · 3 · 2 · 1. It is a worthy exercise to write out all 24 combinations, not only to verify the result but to give practice in how to systematically shuffle the words in an orderly manner—inventing your own functional rules as you go. You might even stumble on why 4 · 3 · 2 · 1 is the right way to count the combinations based on your method of systematizing.

11: ...literally cutting corners

the square, traversed twice as a there-andback trip.

volume is about half that of the cube, so . But where would a go? It’s always a multiplier in these situations, so we can harmlessly throw in a factor to get a volume .The point is that forgetting the exact formulas is not fatal: just back up to a more familiar setting and build out from there. For cylinders, just combine elements of circular and rectangular geometries to realize that the volume is the area of the circle times the height13 of the cylinder. External surface area is twice the areas of the end-caps (each ) plus the perimeter of the circle times the height—as if rolling out the skin into a rectangle and calculating its area.# A.4 Fractions

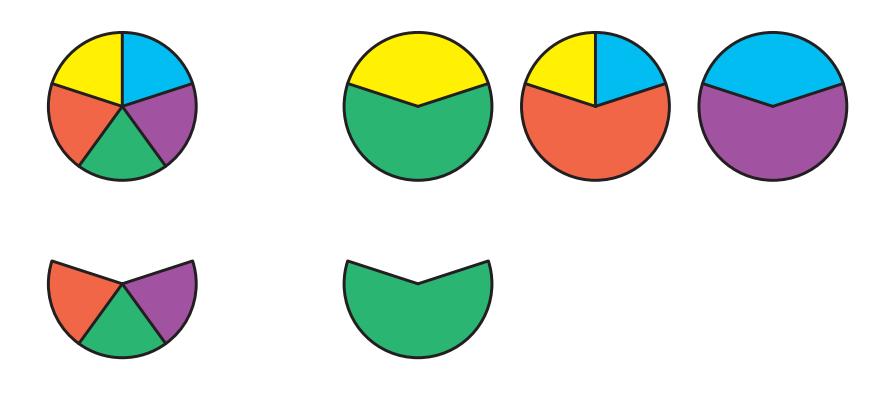

Stressed about fractions? Do you have an intuitive sense for what half a pie ( ) would look like? A fifth of a pie ( )? Which is larger: one-third ( ) of a pie or one-quarter ( )? Do you have an immediate sense of how many quarters are in a dollar? Back to the pie: if a friend hands you two pie plates, each containing a third ( ) of a pie, do you now have less than half of a pie in total, more than half, or exactly half? If you had little trouble picturing and answering these questions, then you’re all set!But isn’t there a lot more to fractions: rules of adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing? What about common denominators and all that business? The point of this section is that you can build on your natural intuition14 to verify and construct the right rules for how the mechanics of fractions should work. You’re not in the dark! 14: ... as expressed in the first paragraphFirst, representation. What does mean? Literally, we can say that we divide something (a pie, for instance) into 5 pieces (denominator) and extract 1 (numerator). Implicitly, we are multiplying the something (pie) by the fraction . Now what about something like ? We can interpret this multiple ways,15 which we will express several ways:

Figure A.1 shows the first two options in Eq. A.1 graphically. We can either slice one pie into five slices and take three of them, or slice three pies into five equal pieces and take one. Either way, we end up with the same amount. The possibilities are endless, and it is worth concocting your own variants. The last steps in Eq. A.1 hint at one type of freedom: we could split one pie into 10 pieces and select 6. Or we could split two pies into ten pieces and take 3 of those to end up with the same amount of pie.Let’s formulate rules about multiplication of fractions based on stuff we know (intuition). What is the rule for the general multiplication of two fractions, expressed symbolically so we can substitute any number3: . . . or length, if on its side

14: . . . as expressed in the first paragraph

15:... all correct, and depends on context

of the problem at hand

for any symbol (placeholder) and get the right answer? In other words, what should the question marks be in the following:

(A.2)

To answer, pick a scenario you already know and back-out the answer. You know that one half of one-half is one quarter. You also know that one half of 4 5 must be 2 5 , or that three thirds must be a whole “one.” In math terms:

(A.3)

From these examples—and others that can be fabricated as wished or needed—it is possible to arrive at the conclusion that

(A.4)

In other words, just multiply the numerators together and multiply the denominators together, simplifying by common factors as needed.

Example A.4.1 What is of the fraction ? By the straight rules, we get 30 in the numerator and 120 in the denominator.16 Many common factors appear in the numerator and denominator (even the original could have been reduced to ) to give the final answer of .

16: We can apply our lesson on reciprocals Many common factors appear in the numerator and denominator (even the original 15 24 could have been reduced to 5 8 ) to give the final answer of 1 4 .One more framing of fractions and their relationship to multiplication and division: dividing by 8 is the same as multiplying by . Multiplying by is the same as dividing by . Multiplication and division are thus essentially the same, only having to flip the number or fraction upside-down into its reciprocal.

How can our intuition assist us in figuring out addition and subtraction of fractions? Use what you know:

(A.5)

Hopefully, the first two statements in Eq. A.5 are apparent enough. The

Figure A.1: Paralleling Eq. A.1, we can slice one pie into five equal pieces (left) and keep three of them (lower left); or we can split three pies into equal-area pieces (same color; sometimes split up across different pies) and take one of the resulting pieces. In both cases, the bottom row is the same amount of pie: 3 5 of one pie equals 1 5 of three pies.

(see Example A.1.2) and realize that multiplying 24 by 5 is a lot like dividing it by 2, up to a decimal place. This gives us something 12–like and thus 120.

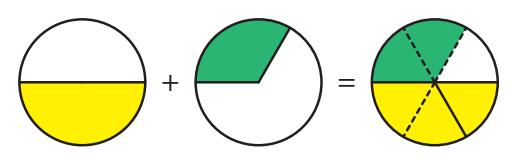

last one bounds the answer by what you already know. Since is larger than .17 So adding must be larger than . By similar logic, since one-third is smaller than one-half,18 their sum must be smaller than 1.Adding fractions like and is where common denominators come in. We can add numerators only if the fractions share the same denominator. We never add denominators. We can’t replicate the middle example in Eq. A.5 by adding numerators and denominators, or we would get the nonsense answer , rather than .So how would we ever recreate the whole common denominator scheme based on intuition? Let’s return to the case of . We have already bounded it to be between 0.75 and 1.0 (in Eq. A.5), which is already useful as a check to whatever rule we might try. Looking at the problem graphically, as in Figure A.2, we see that overlaying and naturally creates a missing gap of . How do 2 and 3 in the denominators conspire to form 6? Via multiplication, of course. Re-expressing as and as , allows us to add the numerators directly, having made the denominators the same: .

To some students, this may seem like an unnecessary and elementary review,20 but the main point is that when in doubt, use what you already know to test your technique and verify that you are doing things right. If the rules you are trying to apply seem to work for a few different known cases, then you’re probably golden. Approaching math this way makes you the boss of the formulas, rather than the other way around. 20: . . . which is why it is relegated to an appendix# A.5 Integer Powers

Raising a number to a power, like 43 , is just a mathematical shorthand for 4 · 4 · 4. Think of all the room we save in the case of 423 !

So what are the rules for dealing with exponents when we raise the whole thing to another power, or when we multiply two exponentiated pieces together, or if we divide by (or invert) the thing? In other words, what are:

(A.6)

The theme of this appendix is: discover the rule through your own experimentation. Tackling in stages, what is ? We can write out 74 as 7 · 7 · 7 · 7 easily enough. If we cube this number, it’s the same as18: If such statements are less than intuitive, think about pie or money, where the natural context lends itself to better intuition.The point of this section (and appendix) is that you can use what you already know to check whether you are applying the right rules, and even re-create the rules that work—verifying that you get the answers you expect for cases you know and trust. Discover for yourself! Doing so gives you full ownership of the math. It’s no longer something someone taught you to do: you’ve taught it to yourself, and that is far more powerful.19 19: . . . by multiplying top and bottom by the missing factor—or the “other” denominator value+ = Figure A.2: Graphically, it is easy to see that . You can always concoct similar/familiar scenarios to verify (and reinvent) the rules.appendix=? (A.6) Notice that the the symbols used in this equation are just stand-ins for numbers, and have no intrinsic significance—whether we use or or for an exponent is irrelevant. For that matter, is not special either and we could have used a hexagon to stand in for the base in these relations, as a symbolic placeholder.writing this set three times, all multiplied together, or (7 · 7 · 7 · 7) × (7 · 7 · 7 · 7) × (7 · 7 · 7 · 7), which is just 12 sevens multiplied, or 712 . So we have discovered/formulated the rule:

We multiply the exponents when raising the inner exponent to an outer one.How about ? What is the rule there? The process21 is similar to before, expanding out to (3 · 3) × (3 · 3 · 3 · 3 · 3), which just looks like seven threes multiplied together, or 37 . Therefore, our rule is:

We add exponents when multiplying two pieces, each having their own exponent. Note that this does not work when the bases are unequal, as you could verify yourself for .Finally, what about inversion, or dividing by ? As a preview, a negative power is equivalent to putting the item in the denominator, so that . To see this, consider Eq. A.8 in the case where and are opposite sign but the same magnitude. For instance, following the “add the exponents rule” we get that , because anything raised to the zero power is 1.22 The only thing we can multiply into in order to get 1 is . This means that 3-4 is the same as , or more generally:

22 Think of the exponent as how many instances of a number are multiplied together in a chain, implicitly all multiplied by 1. If we have zero instances of the number, then

(A.9)

Negative exponents therefore flip the construction to the denominator, or denote a division rather than multiplication.## A.6 Fractional Powers

In the previous section, we only dealt with integer powers, so that we could write out 34 as . How would we possibly write 31.7 ? Yet it is mathematically well defined. A calculator has no trouble.We can get a hint from Eq. A.8. Consider, for example, . We know that we can just add the exponents, which in this case add to a tidy 1, meaning that the answer is just 5. Therefore we interpret as the square root of 5, since multiplying it by itself yields 5. So we can re-express our familiar friend as a fractional power:

In principle, then, we could approach 31.7 by taking the tenth-root of 3 and raising it to 17th power: .© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

where we use the exponential function and its inverse function (natural log, ln), or alternatively the base-10 equivalents. If, for some reason, we lacked a yx calculator button, these approaches allow more fundamental ways to get at the same thing.# A.7 Scientific Notation

The single-biggest mistake students make when it comes to scientific notation is easily remedied by understanding it not as a set of rules, but for what it’s actually doing.Most of the time, students get it right: they see and move the decimal to the right two times to get 160. A little harder is negative exponents, like . Moving the decimal point twice to the left results in the correct 0.024 answer.The hangup can come about if the process is misconstrued as simply “counting zeros.” Ironically, a student might correctly convert by adding three zeros to the 6 to get 6,000, but then mistake 103 for 10,000—thinking: start with 10 and add three zeros.The sure-fire way is to connect to the concept of integer powers, so that 103 is simply 10 · 10 · 10, which is unmistakably 1,000. Likewise, 10-4 is four repeated (multiplied) instances of 10-1 , each one representing , or 0.1. String four together, and we have , or 0.0001. So fall back on the basics.Example A.7.1 We can also apply the rule of multiplying exponentiated quantities covered in Eq. A.8. So times can be written out as (order does not matter), which we can recognize as .What about division: divided by ? Several ways to approach this might be instructive. Let’s ignore the pre-factors (2.4 and 8) for now and focus on the powers of ten. The standard practice is to subtract the exponent in the denominator from that in the numerator: in this case, so that we are left with . We could also represent the 107 in the denominator as 10-7 in the numerator, as per Eq. A.9. Now we just add the exponents to get the same result. Or we could invert the to become and multiply this by .But I want to present the way I would do it to make it easy enough

© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

Students often form a counter-productive dependency on formulas. Experts focus on learning the concept expressed by an equation, since an equation is very much like a sentence that speaks some truth.24 Once the fundamental principle is mastered, the equation or formula is automatic, and can be generated from a place of understanding—which is more permanent than memorization.

24: . . . perhaps within some context or set of assumptionsThe practice is more common and natural than it might seem at first. Let’s say a person has a take-home pay of $50,000 per year. Rent is $2,000 per month, groceries and other bills come to $1,000 per month. How much is left per month for discretionary spending? Where is the formula for that problem? Of course, you wouldn’t bother hunting for a formula in this case and would instead build your own math. You essentially create your own formula on the fly. Whether you first divide the annual figure by 12 and then subtract the monthly expenses, or multiply monthly expenses by 12 before subtracting from the annual amount and then dividing by 12, the result is the same: a little more than $1,000 per month.It is also clear in this context that it makes little sense to perform math down to the penny, since the grocery and other expenses are not going to be exactly the same each month. The lesson is that most people are expert enough in managing money that they don’t scramble to find printed formulas whenever they want to figure something out, and they are also forgiving on precision because they know from context not to take it all too literally.This book tries to foster a more expert-like approach to the material. For instance, Def. 5.3.1 (p. 71) introduces the concept of power without explicitly saying . It just says that power is how much energy is expended in how much time. If a student internalizes that idea, then why print a formula? By doing so, a student may bypass real understanding25 and rely on the formula as a crutch, never planting the core idea firmly in the brain. Shortcuts can end up disadvantaging students, as attractive as they may look in the moment. The student who masters the concepts will be in a far better position to deploy them in a wider variety of circumstances—including unfamiliar test questions.

25: . . . which in this case is not a heavy liftrevels in the reinforcement that comes from consistency.of assumptions25: . . . which in this case is not a heavy lift

A.5A.9 Equation Manipulation¶

Physics instructors often joke that they teach students the “three Ohm’s Laws.” The joke is that only one is needed: . The other forms: and can be derived from the first. Rigid memorization leads some students to remember all three forms, rather than simply move things around in a way that maintains the relationship.The rules are easy enough to generate on your own. Think of an equation as a perfectly balanced see-saw—maybe an elephant sitting on both sides. The equation is only valid if it remains balanced. You may add a chicken, but do it to both sides. You may multiply or divide the number of elephants, as long as it is done the same way to both sides. Dividing both sides of (the first) Ohm’s Law above by 푅 leads to the second form, for instance.

Example A.9.1 Let’s say you are given something you consider to be an ugly equation, or you simply want to solve for one variable. Using symbols for everything,26 we might have [26]: It is easy to substitute numbers any-

Let’s say we hate the appearance of fractions. Multiply both sides by 푏:

푧 Now multiply both sides by 푧 to eliminate the remaining fraction:

What if you wanted a solution for 푦? Guess we’re going to have to return 푏 to denominator status, as we need to divide both sides by 푏.

And finally we subtract 푥 from both sides to get

Whatever you want to do, just do it to both sides.

It’s not always so straightforward. Sometimes we have to “undo” or “invert” a mathematical function. Consider for instance a familiar problem: find the side length, a, of a right triangle whose other side is b and hypotenuse c. We know from the Pythagorean Theorem that , so that . But we want a, not . How do we “undo” the square? Take a page from Eq. A.7. We want a to the power of 1, so we want to raise to whatever power will neutralize the 2 via multiplication.where you wish at any time

Looks like 1 2 (square root) will do the trick. But we need to treat both sides: √ √

In this case, the power can be said to perform the inverse function of the power . In more familiar contexts: subtraction is the inverse of addition; division is the inverse of multiplication. Less familiarly, but in similar veins: the sine is “undone” by arcsine;27 the exponential is undone by the natural log (ln ); is undone by , etc.If you have not done it before (or recently), mess around on a calculator, starting with a custom number you make up that is pleasing to you and recognizable.28 Square it and then take the square root. Calculate the sine and then inverse sine (ASIN). Take the exponential and then natural log—or other way around. Get to know these things on your own terms!

28: Something like 1.23456 would work, but make it your own!these examples

but make it your own!

A.6A.10 Units Manipulation¶

In the real world, numbers often are packaged with associated units. The radius of the earth is 6,378 km. If we change the unit, we change the number, too. Earth’s radius becomes 6,378,000 m or 3,963 miles. Most generally, we aim to quantify something in nature, and the numeric value is utterly dependent on the units we choose to represent the physical reality.

Because the numbers are often meaningless without the accompanying units, we should29 29: Full disclosure: I don’t always do so, in carry around the units in all manipulations. Any time we do something to the number, we need to do the same thing to the unit.

Example A.10.1 If we travel 4 meters in 2 seconds, we have

Dividing the numbers alone to get 2 is not the whole story. We also divided the units to create a new one that was not in the initial set (m and s).

If we fill a room whose floor area is 10 square meters with water one meter deep, the volume is

So we multiply the meters together just like we do the numbers, following the same rules but acting as if they are variables and keeping it symbolic.

© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

haste. But I know they belong there and will throw them back in if I get tangled or end up suspecting a nonsense result.

More complicated arrangements follow the same rules. For example, the force of drag30 on an object moving at speed through a medium of density is , where is the frontal (cross-sectional) area of the object and is the dimensionless drag coefficient.31 The dimensions of area are m2; density is kg/m3 (mass per volume), and velocity is m/s (distance over time). The whole arrangement therefore has dimensions:

The end result matches the definition of Newtons, and can be verified by the (possibly familiar) form of Newton’s Second Law,32 whereby 32: Force equals mass times acceleration we have mass in kg times acceleration in m/s2 making kg · m/s2.When performing a chain of multiplications or divisions, we can carry the units around and multiply, divide, or (hopefully) cancel them as we go.

Example A.10.2 Let’s say we want to know how much energy, in Joules, the U.S. uses in a year based on knowledge that the average citizen accounts for 10,000 W (a Watt is a Joule per second) and the U.S. has 330 million people. First, let’s work with the 10,000 W per person metric:

where we have just moved the seconds into the denominator to multiply “person” (order doesn’t matter). Most of the problem is in going from seconds to years. It would like like this:

Notice that each of the factors we multiply, even though they carry a non-unity numeric value, are essentially identities that describe equal intervals on top and bottom, in differing units.33 So we are effectively multiplying by 1 repeatedly in a unit conversion process. 33: E.g., 24 hours and 1 day describe theAlso note that the chain we construct allows a boatload of cancellations, as almost all units present appear in both the numerator and denominator once. The only ones that do not are J in the numerator and year and person in the denominator. When we carry out the multiplication above and cancel units, we find that we are left with:

Oops, the units are helping us here by reminding us that we need to multiply by the population (3.3 × 108 persons) to get the answer 30: This choice is intentionally unfamiliar and complicated–looking to demonstrate that units can help bring a sense of order and correctness even in alien contexts.

31: The drag coefficient, 푐D, is usually in the range 0.3–1.

32: Force equals mass times acceleration

same time interval.

we sought.34 34: So units, handled carefully, can provide In this case, we end up with 1.04 × 1020 J/year, which is what we were after.

We just carried out unit conversions (in time) in Example A.10.2, when we multiplied by constructs like 60 s/1 min. The key to unit conversions is to arrange a fraction expressing the same physical thing in both the numerator and denominator, just using different units. So we’re looking for equivalent measures. Most of the time, one of them will be 1, numerically, as in the following example.

Example A.10.3 We might want to convert the 1.04×1020 J/year from Example A.10.2 into quadrillion Btu per year. We know that 1 Btu is 1,055 J, and that a quadrillion is 1015. So we arrange the following:

Finally, units can help guide correct usage of factors in a problem. In Example A.10.3, what if we did not know whether to divide or multiply by 1,055? The fact that we wanted to eliminate Joules told us we needed the Joules in the denominator, and so the relation 1 Btu = 1,055 J told us the 1,055 travels with Joules and must be in the denominator.

But what if we are faced with a problem whose application is not as apparent?35 35: . . . or we don’t know the formula, which Let’s explore how this might go in a less familiar setting.

Example A.10.4 For some inexplicable reason, you put a brick in the refrigerator, which is 20oC colder than the brick is, initially, and want to find out how long it will take for the brick to cool off. The brick has a mass of 2.5 kg, will dump its heat into the refrigerator at a rate of 10 W (10 J/s), and has a specific heat capacity of 1,000 J/kg/oC.36 So you feel overwhelmed by lack of familiarity, right? Good, because the units are here to help.You want an answer in time units, and see one instance in the 10 J/s rate at which heat leaves the brick. To get seconds “up top,” you want to make sure the 10 W value is in the denominator. This puts Joules in the denominator, and we don’t want it to survive to the final answer. We notice Joules in the specific heat capacity thing in the numerator, so that thing must go in the numerator. Let’s take stock of where that leaves us.

It looks like if we multiply by the mass in kg and multiply by the temperature difference, we’re home free. Doing so results in 5,000 seconds. Whenever possible, try to extract the most context/intuition out of an answer as you can. Does 5,000 seconds mean a lot to you? Divide by 60 (or multiply by 1 min 60 s ) to get 83 minutes. Better. Or another factor of 60 and we’re at 1.4 hours. That seems like the most natural

© 2022 T. W. Murphy, Jr.; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Lic.; Freely available at: https://

important clues as to how to get the problem right.

is no bad thing, as we then have the chance to construct it from what we know, like a real expert!

36 36: This construction means that kg and ◦C are both in the denominator together.

A.6.0.1way to express the answer.¶

It is also useful to pause and reflect on our operations and whether they made sense. For instance, since we multiplied by mass to get the cooling time, it implies that a larger brick would take longer, which is sensible. If heat left at a rate faster than 10 W, it would cool down faster, again making sense.

We will do one more example in an unfamiliar context, this time involving you to accomplish a task. some ambiguity that your wits can help resolve.

Example A.10.5 An outer wall on a sealed brick building measures 5 m long and 2.5 m high, having a thickness of 0.1 m. You are asked how fast heat (thermal energy) is being lost through the wall.37 37: The units would be energy per time, or It is 20◦C warmer inside the wall than it is outside, and you are told that brick has a thermal conductivity of 0.6 W/m/◦C. Thermal what? But don’t panic.

We want an answer in J/s, or W. We see Watts in the numerator of the thermal conductivity, so we want that in the numerator of our answer. We would need to multiply by meters and by

oC to cross the finish line. Seems simple enough. But meters shows up three times in the dimensions of the wall. Which should we choose? Or is it a combination?Engage the intuition. Put yourself in the building next to the wall, mentally. It’s warm inside, cold outside. Will I need more heaters (power) or fewer if the wall is taller? If the wall is wider? If the wall is thicker? What does your intuition say?

You might reason that a thicker wall will require less power to keep warm, but that a larger area (increasing width or height or both) would make the job of maintaining temperature more challenging. This suggests that the power will increase if width or height increase, and decreaseif thickness increases. So we should multiply by width and height (or equivalently, by area) and divide by thickness. Area over thickness indeed has units of meters, which we already concluded we needed as a multiplier to get our desired outcome. Putting things together, we have

which is about the output of one space heater.

A.7A.11 Just the Start¶

It is well beyond the scope of this book to engage in an exhaustive review of math concepts. Hopefully what has been covered provides a At this point, we could create our own formula based on requiring the units to work! See: formulas are not sacred tablets to be memorized—they are just statements that make logical sense and can be created by

J/s, which is a power (W).

38 38: This construction means that m and ◦C are both in the denominator together.

useful foundation. The key lesson is that the knowledge and intuition students already hold in their heads can be leveraged effectively to recreate forgotten rules of math. Just remember: it all makes sense and hangs together. Creating customized simple problems39 39: . . . whose answers are already known allows a way to make sure the math rules being applied replicate the right answer. If not, a few tests can often get things back on the right track. By doing so, students can claim greater personal ownership of the math, and have a better internal mastery of its workings.

or can be figured out