Chapter 1 - The Nature of Physics

1.1Overview¶

1.2Science and the Scientific Method¶

Science is a process for describing the world around us. It seeks explanations for observed phenomena that rely on natural causes. Science assumes that the universe is orderly, reasonable, and testable. The scientific method relies on the creation and testing of models that explain natural phenomena as simply as possible and can be revised when new evidence is discovered. If we come up with a model that can describe many observations, or the outcome of many different experiments, then we usually call that model a scientific theory.

We can get some insight into the Scientific Method through a simple example. Imagine that we wish to describe how long it takes for a tennis ball to reach the ground after being released from a certain height.

One way to proceed is to describe how long it takes for a tennis ball to drop , and then to describe how long it takes for a tennis ball to drop , etc. We could generate an extensive table showing how long it takes a tennis ball to drop from any given height. Someone would then be able to perform an experiment to measure how long a tennis ball takes to drop from or and see if their measurement disagrees with the tabulated values. If we collected the descriptions for all possible heights, then we would effectively have a valid and testable model that describes how long it takes tennis balls to drop from any height.

Suppose that a budding scientist, let’s call her Chloe, noticed that there is a pattern in the data that can be described much more succinctly and generally than by using a long table. In particular, suppose that she notices that, mathematically, the time, , that it takes for a tennis ball to drop a height, , is proportional to the square root of the height:

A mathematical model that can describe a pattern in a set of observations is often called a law.

Chloe’s “law of falling tennis balls” is appealing because it is succinct, and because it allows us to make verifiable predictions. That is, using this law, we can predict that it will take a tennis ball times longer to drop from than it will from , and then perform an experiment to verify that prediction. If the experiment agrees with the prediction, then we conclude that Chloe’s law adequately describes the result of that particular experiment. If the experiment does not agree with the prediction, then we conclude that the law is not an adequate description of that experiment, and we try to find a new model or law that is more universal.

Chloe’s law is also appealing because it can describe not only tennis balls, but the time it takes for other objects to fall as well. Scientists can then set out to continue testing her law with a wide range of objects and drop heights to see if it correctly predicts the outcome of those experiments. Inevitably, they will discover situations where Chloe’s law fails to adequately describe the time that it takes for objects to fall. (Can you think of an example?)

Scientists would then set out to develop a new “law of falling bodies” that would include Chloe’s law while also incorporating an additional description for cases that do not follow Chloe’s law. There is of course no guarantee, ever, that such a law would exist; it is just an optimistic hope of physicists to find the most general and succinct description of the physical world.

In fact, Galileo Galilei derived just such a law of falling bodies in the late 1500s. Galileo conducted experiments using a ball on an inclined plane to determine the relationship between time and distance travelled. He found that distance depended on the square of the time, and that the relationship was the same regardless of the weight of the ball used in the experiment. (You can check and see that this is the same as Chloe’s law.) One hundred years later, Isaac Newton expanded upon Galileo’s work when he proposed that a force he called gravity influenced the motion of all falling objects, including the moon. His Universal Law of Gravitation (Chapter xx) states that objects are attracted to one another with a force proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them:

In simple terms, the greater the mass the greater the gravitational force, and the farther apart two objects are the weaker their attraction. Under this force, the Moon continuously falls towards the Earth, just like Chloe’s tennis ball. The law of gravity unified the phenomena of falling objects on Earth with the orbit of the Moon and demonstrated that the heavens are governed by the same principles that act on Earth.

Following the 1781 discovery of the planet Uranus by William Herschel, astronomers noticed that the orbit of the planet was not well described by Newton’s theory. This led Urbain Le Verrier (in Paris) and John Couch Adams (in Cambridge) to predict the location of a new planet that was disturbing the orbit of Uranus rather than to claim that Newton’s theory was incorrect. The planet Neptune was subsequently discovered by Le Verrier in 1846, one year after the prediction, and seen as a resounding confirmation of Newton’s theory.

In 1859, Urbain Le Verrier also noted that Mercury’s orbit around the Sun is different than that predicted by Newton’s theory. Again, a new planet was proposed, “Vulcan”, but that planet was never discovered. The deviation of Mercury’s orbit from Newton’s prediction remained unexplained until 1915 when Albert Einstein introduced the theory of general relativity, describing gravity as a manifestation of curved spacetime rather than a force between massive objects. Einstein’s revolutionary theory created a single framework for understanding the motion of both light and matter, and has led to discovery of such phenomena as black holes and gravitational waves.

Figure 1:An artist’s impression of gravitational waves generated by binary neutron stars. Credit: R. Hurt/Caltech-JPL

This is a good example of the scientific method; although the discovery of Neptune was consistent with Newton’s theory, it did not prove that the theory is correct, only that it correctly described the motion of Uranus. The discrepancy that arose when looking at Mercury ultimately showed that Newtons’ theory of gravity fails to provide a proper description of planetary orbits in the proximity of very massive objects (Mercury is the closest planet to the Sun).

Figure 2:credit: University of California Museum of Paleontology, Understanding Science, www

Many people have the misconception that the scientific method is a linear, step-by-step process. As we have seen, that is not how science works. The scientific method is a complex and iterative process that involves making observations and asking questions, gathering and interpreting data, and gathering feedback from the scientific community. New discoveries inspire new questions and new directions for research. Answering one question may lead to a deeper understanding or to an entirely new theory.

1.3Theories, hypotheses and models¶

The word “theory” implies uncertainty to most people – an educated guess or idea about the natural world that can be tested. But that is not what scientists mean when we use the word theory. A scientific theory, such as the “Theory of Plate Tectonics,” or the “Theory of General Relativity” is a coherent set of explanations for a large number of facts and observations about the natural world. It must be grounded in evidence, tested against a wide range of conditions, and it must be effective in problem solving and making predictions.

A hypothesis is a question or idea about the natural world, often based on a theory or law, that can be tested. We can formulate a hypothesis based on the theory and then test that hypothesis. If the hypothesis is found to be invalidated by experiment, then either the theory is incorrect, or the hypothesis is not consistent with the theory.

A model is a situation-specific description of a phenomenon that allows us to make a specific prediction. A model that can be succinctly described by an equation is often called a scientific law. Using the example from the previous section, our model would be that the fall time of an object is proportional to the square root of the drop height, and a law would be the precise mathematical description of that model. From the model, we can form a testable hypothesis of how long it will take the tennis ball to fall a given distance. It is important to note that a model will almost always be an approximation of the theory applied to describe a particular set of conditions. For example, if Chloe’s law is only valid in vacuum, and we use it to model the time that it takes for an object to fall at the surface of the Earth, we may find that our model disagrees with experiment. We would not necessarily conclude that the law is invalidated, if our model did not adequately apply the theory to describe the phenomenon (e.g. by forgetting to include the effect of air drag).

This textbook will introduce the theories from Classical Physics, which were mostly established and tested between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. We will take it as given that readers of this textbook are not likely to perform experiments that challenge those well-established theories. The main task will be, given a theory, to define a model that describes a particular situation, and then to test that model. This introductory physics course is thus focused on thinking about “doing physics” as the task of correctly modelling a situation.

1.4The scope of Physics¶

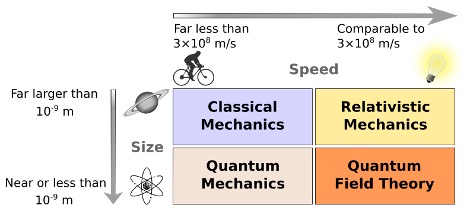

Physics describes a wide range of phenomena within the physical sciences, ranging from the behaviour of microscopic particles that make up matter to the evolution of the entire Universe. We often distinguish between “classical” and “modern” physics depending on when the theories were developed, and we can further subdivide these areas of physics depending on the scale or the type of the phenomena that they describe. This textbook is focused on classical physics, which corresponds to the theories that were developed before 1905.

Figure 3:Classical mechanics works for larger and slower objects; modern theories are needed otherwise. Credit: Yassine Mrabet.

The word physics comes from Ancient Greek and translates to “nature” or “knowledge of nature”. The goal of physics is to develop theories from which mathematical models can be derived to describe our observations. One of the most ambitious goals of physicists is to develop a single theory that describes all of nature, instead of having multiple theories to describe different categories of phenomena. That is, physicists hope that there exists one single mathematical theory (like Chloe’s theory of falling objects) that describes the entire physical universe. In Biology, for example, this would not be a reasonable goal, as one needs to describe every single living being, and there is no overarching “theory of what all living things look like.” Currently, physicists have been able to narrow down the number of theories required to describe all of the physical world to only three, which is impressive (the theory of gravity, the theory of the strong nuclear force, and physicists have now further unified the weak nuclear force with electromagnetism to make the “electroweak force”).

1.4.1Classical Physics¶

\subsubsection{Mechanics} Mechanics describes most of our everyday experiences, such as how objects move, including how planets move under the influence of gravity. Isaac Newton was the first to formally develop a theory of mechanics, using his “Three Laws” to describe the behavior of objects in our everyday experience. His famous work published in 1687, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (“The Principia”) also included a theory of gravity that describes the motion of celestial objects, as we have seen. In Newtonian mechanics the motion of a particle is determined exactly by a small number of parameters, including its mass, position, and the forces applied to it. Classical mechanics assumes that matter and energy have definite, knowable properties such as location in space and speed, and that forces act instantaneously.

Conservation laws are fundamental laws of nature with broad applications in all areas of science and engineering. Conservation laws describe certain properties of nature that remain unchanged during physical interactions. For example, the conservation of energy states that the total amount of energy in an isolated system does not change, although it may take different forms. In classical mechanics, we are primarily concerned with the conservation of energy, and the conservation of linear and angular momentum.

1.4.2Electromagnetism¶

Electromagnetism describes electric charges and magnetism. At first, it was not realized that electricity and magnetism were connected. Charles Augustin de Coulomb published in 1784 the first description of how electric charges attract and repel each other. Magnetism was discovered in the ancient world, when people noticed that lodestone (rocks made from magnetized magnetite mineral) could attract iron tools. In 1819, Oersted discovered that moving electric charges could influence a compass needle, and several subsequent experiments were carried out to discover how magnets and moving electric charges interact.

In 1865, James Clerk Maxwell published “A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field”, wherein he first proposed a theory that unified electricity and magnetism as two facets of the same phenomenon. One important concept from Maxwell’s theory is that light is an electromagnetic wave with a well-defined speed. This uncovered some potential issues with the theory as it required an absolute frame of reference in which to describe the propagation of light. Experiments in the late 1800s failed to detect the existence of this frame of reference.

1.4.3Modern Physics¶

In 1905, Albert Einstein published three major papers that set the foundation for what we now call “Modern Physics”. These papers covered the following areas that were not well-described by classical physics:

A description of Brownian motion that implied that all matter is made of atoms.

A description of the photoelectric effect that implied that light is made of particles.

A description of the motion of very fast objects that implied that mass is equivalent to energy, and that time and distance are relative concepts.

In order to accommodate Einstein’s descriptions, physicists had to dramatically re-formulate new theories.

1.4.3.1The Special and General Theories of Relativity¶

In 1905, Einstein published his “Special Theory of Relativity”, which describes how light propagates at a constant speed without the need for an absolute frame of reference, thus solving the problem introduced by Maxwell. This required physicists to consider space and time on an equal footing (“space-time”), rather than two independent aspects of the natural world, and led to a flurry of odd, but verified, experimental predictions. One such prediction is that time flows slower for objects that are moving fast, which has been experimentally verified by flying precise atomic clocks on airplanes and satellites. In 1915, Einstein further refined his theory into General Relativity, which is our best current description of gravity and includes a description of Mercury’s orbit which was not described by Newton’s theory.

1.4.3.2Quantum mechanics and particle physics¶

Quantum mechanics is a theory that was developed in the 1920s to incorporate Einstein’s conclusion that light is made of particles (or rather, quantized lumps of energy called quanta) and describe nature at the smallest scales. This could only be done at the expense of determinism, the idea that we can predict how particular situations evolve in time. This led to a theory that could only provide the probabilities that certain outcomes will be realized. Quantum mechanics was further refined during the twentieth century into Quantum Field Theory, which led to the Standard Model of particle physics that describes our current understanding of matter through the theories of the electroweak and strong forces.

1.4.3.3Cosmology and astrophysics¶

Cosmology describes processes at the largest scales and is mostly based on applying General Relativity to the scale of the Universe. For example, cosmology describes how our Universe started from the Big Bang and how large scale structures, such as galaxies and clusters of galaxies, have formed and evolved into our present day Universe.

Figure 4:A galaxy in the Coma cluster of galaxies (credit:NASA).

Astrophysics is focused on describing the formation and the evolution of stars, galaxies, and other “astrophysical objects” such as neutron stars and black holes.

1.4.3.4Particle astrophysics¶

Particle astrophysics is a relatively new field that makes use of subatomic particles produced by astrophysical objects to learn both about the objects and about the particles. For example, the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Art McDonald (a Canadian physicist from Queen’s University) for using neutrinos[1] produced by the Sun to both learn about the nature of neutrinos and about how the Sun works.

1.5Thinking like a physicist¶

Studying physics, we learn very quickly that certain theories, such as quantum mechanics, are very counter-intuitive. For example, in quantum mechanics, an object can be described as being in two locations at the same time. In the theory of special relativity, it is possible for two people to disagree on whether two events occurred at the same time. These particular predictions from these theories have not been invalidated by any experiment.

There is no requirement in science that a theory be “pretty” or intuitive. The only requirement is that a theory describe experimental data. One should be careful not to rely too heavily on preconceptions when interpreting a theory or analyzing data from an experiment. For example, quantum mechanics does not actually predict that objects can be in two locations at once, only that objects behave as if they were in two locations at once. A famous example is Schrödinger’s cat, which can be modelled as being both alive and dead at the same time. However, just because we model it that way does not mean that it really is alive and dead at the same time.

In a sense, physics can be thought of as the most fundamental of the sciences, as it describes the interactions of the smallest constituents of matter. In principle, if one can precisely describe how protons, neutrons, and electrons interact, then one can completely describe how a human brain thinks. In practice, the theories of particle physics lead to equations that are too difficult to solve for systems that include as many particles as a human brain. In fact, they are too difficult to solve exactly for even rather small systems of particles such as atoms bigger than helium (containing several protons, neutrons and electrons).

We have a number of other fields of science to cover complex systems of particles interacting. Chemistry can be used to describe what happens to systems consisting of many atoms and molecules. In a living being, it is too difficult to keep track of systems of atoms and molecules, so we use Biology to describe living systems.

One of the key qualities required to be an effective physicist is an ability to understand how to apply a theory and develop a model to describe a phenomenon. Just like any other skill, it takes practice to become good at developing models. Students that graduate with a physics degree are thus often sought for jobs that require critical thinking and the ability to develop quantitative models, which covers many fields from outside of physics such as finance or Big Data. This textbook thus tries to emphasize practice with developing models, while also providing a strong background in the theories of classical physics.

1.6Summary¶

Science attempts to describe the physical world (it answers the question “How?”, not “Why?”).

The Scientific Method provides a prescription for arriving at theories that describe the physical world and that can be experimentally verified. The Scientific Method is necessarily an iterative process where theories are continuously updated as new experimental data are acquired. An experiment can only disprove a theory, not confirm it in any general sense.

Physics covers a wide scale of phenomena ranging from the Universe down to subatomic particles. Classical physics encompasses the theories developed before 1905, when Einstein introduced the need for Quantum Mechanics and the Theorie(s) of Relativity. One of the main goals of physics is to arrive at a single theory that describes all of our natural world. Currently, physicists require three theories to describe the natural world.

1.7Thinking about the Material¶

1.8Sample problems and solutions¶

1.8.1Problems¶

1.8.2Solutions¶

Solution 1.1

a) You could do an investigation to see if the government is spreading chemicals, and try to find out why. You could make measurements of the contents in the atmosphere before and after an airline passes to see if any unexpected chemicals show up.

b) No he is not, as you just proposed two experiments that could invalidate his theory.

Solution 1.2

a) and b)

The cruise control may have some uncertainty associated with the set speed.

You start and stop your watch at slightly different locations.

There could be tailwinds and headwinds that speed up and slow down the car.

c)

Repeat tests on days with no wind to eliminate tailwind and headwind effects.

Construct a method for starting and stopping your watch at the same locations to eliminate timing effects.

Neutrinos are the lightest subatomic particles that we know of.